Unearthing the discord in our discourse

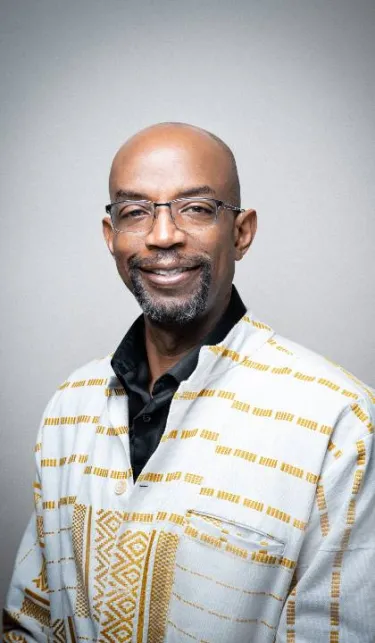

MidWinter Lecturer Dr. Reggie L. Williams dismantles hierarchies in defining what is human

The European tradition that shapes how we define who is and who is not human is centered on a male protagonist, explained Dr. Reggie L. Williams, the associate professor of Black Theology and African American Studies at St. Louis University.

Williams delivered the E.C. Westervelt Lectures on Tuesday and Wednesday. These two lectures, established in 1949, are a part of Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary’s MidWinter Lectures, which featured five other lectures, several “tiny talks” and worship opportunities over the course of a three-day in-person and virtual event.

Williams, the author of “Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance,” said he was simultaneously at work on two more books, an academic work titled “Wholy Holy: An Ethics After Whiteness” and another trade book called “Bonhoeffer Conundrum: A Complicated Christian Engagement with Fascism.”

Williams’ first lecture focused on the discord sown in the discourse we use to identify ourselves as human, while the second presentation turned to ways of knowing and being in Black artistry for a vision of ourselves as unified beings.

“The central figure animating our understanding of everything, including God,” Williams said, describing a singular male protagonist who lives in a world dependent on “distinction, difference and antagonism. The European version of this character is what we are living, and he needs contrast in order to be seen,” said Williams.

On Tuesday morning, Williams presented what he titled “The Problem of the Human as a Problem of Life Together,” in which he looked at the binaries present in the discourse of Western ethics. Particularly, he looked at what understanding of humanity was omitted from “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” approved by 48 nations in 1948, three years after the end of World War II. According to committee chair Eleanor Roosevelt, there was debate on the committee about how Western the ideas were that guided the document. Williams traced how its ideas belonged to a genre of statements on the rights of man and the definition of citizens that included the United States’ Declaration of Independence and 1789’s French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, essential to its revolution. While the 1948 statement was not legally binding, it held another kind of creative power within a tradition of dominant discourse. “Discourse is ‘language that creates a knowledge of reality,’” said Williams, quoting cultural critic Sylvia Wynter.

In 1948, most of the continent of Africa and the Caribbean remained colonized by those who wrote the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; therefore, in crafting it, the language of “self-determination” that inspired the previous declarations was omitted. Including this characteristic of humanity “would have put those signatories out of bounds, ethically, by their own admission,” said Williams.

“They highlighted a version of dignity for the colonized that refused their rights to self-governance, betraying European perceptions of human difference that separate the colonized from their colonizers,” said Williams. This separation sustained the hierarchy inherent in Western thought, where an ideal designed to define ends up dissecting and dominating others and what Williams’ termed “otherwise” realities. Even in stating “universal human rights,” signatory nations repeat dehumanizing binaries in which the human citizen and colonizing nation stand above colonized bodies and nations.

Williams pointed out how cosmologies were once hierarchal. The sun moved around the Earth, and hell lay beneath it. A human is not an animal, but neither is he divine (and yet, he gets to define who God is). Internally, he struggles in his station between flesh and spirit, between damned behavior and divine inspiration. According to Williams, although science has proven otherwise, Western culture continues to center the singular Earth and its self-determining protagonist.

“Through the advancements of science, which some Christians fear and hate, you will come to recognize that the universe is different, a beginning and an expansion,” said Williams, who asked, “What does our understanding of God look like in light of this? How does our theology recognize our existence in this reality?”

Williams wondered who we are when we don’t use ideals to define who we are not and antagonize those whom we determine are not like us.

On Wednesday morning, Williams set out to address this through the embodiment of Black artistic expression. He described the humanity portrayed through musical traditions spanning from spirituals to the gospel and popular music of Marvin Gaye and Aretha Franklin and Harlem Renaissance writers and visual artists drawing on African tribal art.

In this second lecture, “Wholy Holy: A Black Artistic Suggestion for Christian Ethics,” Williams asserted that racism is “not about our feelings about other people,” for those are just symptoms of us enacting the hierarchies that have defined us and our realities; rather, racism “is embedded in the way we know human difference in general.”

“The introduction to this way of thinking initially can be a bit like trying to tell a fish that you're breathing water,” said Williams. “How do you explain what water is to a fish?” Williams then described how only those looking from the shore can give you a clearer sense of what you’re inside of. “Europe gave us an idea of human difference,” which set in motion justifications “for colonialism, slavery and capitalism.”

It is in the creative expression of those who have survived on the margins that a more holistic portrait of humanity emerges, like the one Franklin offers in her performance of Gaye’s “Wholy Holy” in 1972.

Through playing a recording of her historic performance at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles, Williams allowed Franklin to sing her own testimony to humankind’s capacity for unity:

”Wholy holy. Come together wholly …

We’ve got to come together …

because we need the strength, the power and all of the feelings.

Wholy holy.

We should believe in each other’s dreams. We’ve got to come together.

We believe in one another.

We believe in Jesus.

Jesus left a long time ago, and said he would return.

He left us a book to believe in,

And we’ve got a lot to learn.

Wholy holy.

We can conquer hate forever …

Oh Lord, we can rock the world’s foundation …

Wholy holy.

Holler love across the nation.

Wholy holy.

We proclaim love, our salvation.

Wholy holy.”

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.