Lining out subtle differences among repair, reparations and restorative actions

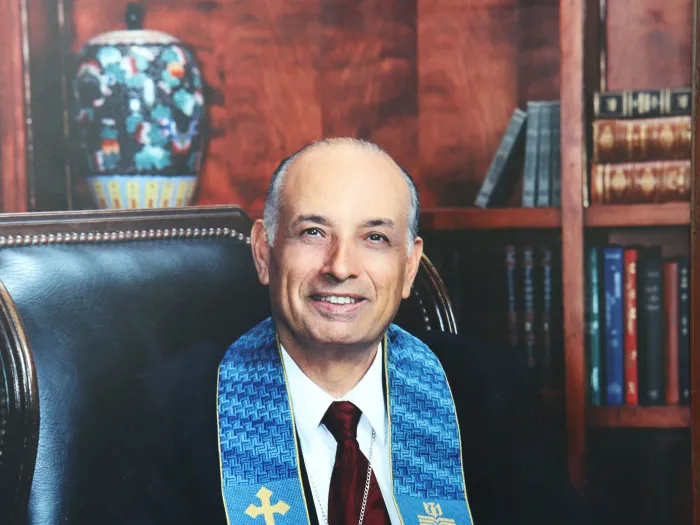

The Rev. Jermaine Ross-Allam is the most recent guest on ‘Leading Theologically’

LOUISVILLE — Building on a series that’s looking at reconciliation, repair and reparations, “Leading Theologically” host the Rev. Bill Davis this week turned his microphone toward the Rev. Jermaine Ross-Allam, director of the PC(USA)’s Center for the Repair of Historic Harms. Listen to their 26-minute conversation here.

At the Center for Repair, two things “must happen at the same time,” Ross-Allam said. “On the one hand, Presbyterians have repairs to make that are internal to our denomination” and have “specific things to do with how caucuses have been treated and how specific congregations have been treated,” he said. “We look at what has been called for in terms of repair so we can begin repair precisely where the repair is being called for.”

At the same time and “on a larger scale, both nationally and internationally, we recognize that Presbyterians as a family have participated in damages that are now far beyond our capacity to remedy on our own.” Those damages include such actions as the Indian removal process.

Presbyterians “refuse to submit to a council of despair and say, ‘oh well, let’s just let bygones be bygones,’” he said. “Instead, we engage in strategic partnerships with other groups who are also called upon to address those historic harms, so that we can take a humble approach and realize that yes, there is something we can and must do, but no, we cannot do it on our own. For those reasons, we partner with others to move those repair agendas forward.”

Those agendas include Indigenous issues from land-back claims and other issues regarding Indigenous sovereignty, he said. They also involve dealing with the legacies of chattel slavery “and Presbyterians’ frankly-speaking forked-tongue approach in the 19th century.” One example is the production of slave sermons, “or [19th century] sermons that are designed to prevent insurrections among enslaved people or work stoppages among slaves, etc.”

The work “is very broad,” and that’s led the Center for Repair to partner with the World Council of Churches, the National Council of Churches and even the United Nations, “where our partnerships are being called for. We also engage in more intimate, faithful work,” including responding to overtures approved during recent General Assemblies. One “instructs us to help congregations with a majority of people of color in them find ways to call full-time pastoral leadership despite difficulties meeting presbytery [compensation] minimums, retiring debt responsibly, etc.”

“There’s lots of good work underway,” Ross-Allam told Davis. “We’ll have plenty to do for the foreseeable future.”

When asked for succinct definitions for terms including repair, reparations and restorative actions, Ross-Allam began with reparations, which he said “has always been kind of a dirty word” for U.S. politicians and in the nation’s social life. “People have understood the call for reparations as being counterproductive, and that it can become a distraction from Afro-Americans living fully into the vocation of citizenship.”

“Reparations nevertheless depends on whatever is being called for by a distinct group of people,” Ross-Allam said. “That becomes extraordinarily important when we look at the different sectors of the African diaspora, and it becomes increasingly important as well when we take into consideration that Indigenous groups in the United States do not call for one particular thing as reparations for all Indigenous nations, but as sovereign nations call for the repairs that are distinct to each group’s history and preferred future.”

That’s why Ross-Allam and others make a distinction between reparations “and other reparative activities or reparative justice paradigms, and the activities that go along with those,” he said. The economist William Darity Jr. and writer Kristen Mullen have said closing the wealth gap between white people and Black people would result in a reparation payment of up to $12 trillion, “which as you know is far beyond what the Presbyterian Church or any combination of denominations can pay,” Ross-Allam said. “It’s even beyond what an individual city or state can pay. Because we realize that scale of reparation requires a nation-state and, in some cases, a combination of nation-states to satisfactorily close, we must distinguish what must be done on that level from what can only be done on the smaller level by a distinct group of people.”

Repair “has to do with the total activity that we can do as Christian people in order to deal with the possibility of and the biblical requirement of total transformation from the types of people that we’ve become” as “colonized or colonizing Christians to the Christians and human beings we are able to become through the power of the Holy Spirit,” he said. “This is where we see the value of local repair.”

When former President Barack Obama and musician Bruce Springsteen had their short-lived podcast, Obama explained that he didn’t prioritize reparations in his presidency “because, to paraphrase, he did not believe that white voters and African, Asian and Latinx immigrants would stand for it, or go for it,” Ross-Allam said. “He thought it would be counterproductive to other civil rights interests.”

“What that teaches us is the church has a very unique role as a moral community to see to it that we play our appropriate role in changing public opinion so that the next Barack Obama will have to say instead that we can’t get anything done if we don’t take these reparations and reparative justice people seriously.”

He called apologies “a very important way of beginning work that ends with reparations.” But “if we just apologize, we’re really deceiving ourselves into thinking there is something right about saying something that is correct without following those words up with deeds that really show the fruit of repentance.” The Center for Repair follows a call and response repair effort that says, “it is the responsibility of people and communities who have experienced oppression to call for the repairs that they seek. … We listen to the calls for repair that come to us and we begin a conversation that allows us to understand what our responsibilities are and what our response capabilities are so that the repair we engage in will be the beginning of a new relationship …”

“With that approach, we frequently learn that people are interested in acknowledgements and apologies,” he said. “But they are also interested in moving forward together with Presbyterians in a future that takes up the best of what was intended before but eliminates to the greatest extent possible those things from the past that were harmful, either by intent or accident. That’s a helpful approach, because it avoids taking a permanent position of benefactor. It avoids us looking at people and saying, ‘Oh, you poor thing, what did we do to hurt you? How can we help you so that we can go about feeling better about ourselves?’”

“We also seek to avoid the opposite,” he said, “where we are in the permanent position of the penitent, constantly chastising ourselves as if we can’t take the opportunity into our own hands to improve areas where we’ve done wrong and move forward as equal partners with different constituents.”

The Center for Repair “is thrilled to be engaged in Project 180,” Ross-Allam said, which celebrates the coming 180th anniversary of Liberia’s independence. An overture will be considered by commissioners to the 227th General Assembly (2026) “that shows ways we can look at the relationship between the Presbyterian Church and the people of Liberia and examine what was not the greatest in the relationship 200 years ago and learn how we can move step by step toward improving our relationship.”

“We can then continue to partner with the people of Liberia as they look for partners in recovery from the civil conflicts that devastated that country at the end of the 20th century,” he said. “’180 Degrees’ is our way of saying we want to take our relationship and turn it all the way around so we can look at the beginning once again, learn what we need to learn about the beginning and then move forward with greater faithfulness.”

Asked by Davis what’s the best thing he’s heard recently, Ross-Allam responded with some readings by Dr. Malidoma Somé, who’s written “about the significance of connecting with our ancestry,” Ross-Allam said. “He said our ancestors are always looking to see whether or not we are hospitable to their presence so that through us they can complete work in the world that they were not able to complete in their lifetimes.”

Somé, who comes from the Dagra tradition of people who live in Burkina Faso, “reminded me that as a Christian, I have an opportunity to make myself hospitable for the work of the Holy Spirit to be real and alive in the world through spiritual discipline,” Ross-Allan said. “I name that because we often don’t associate spiritual discipline with the work of justice. Some people bifurcate the two,” but “part of what the Reformed tradition is doing and must continue to do throughout the 21st century is to remember that the Holy Spirit is not just an afterthought. The Holy Spirit is very much God, and the Holy Spirit desires to animate our bodies so that we can not only realign ourselves spiritually as individuals, but so that we can renew our collective mind and offer our collective body as living sacrifices, to use the Apostle Paul’s language, so that our bodies become instruments of God’s justice and God’s compassion and God’s peace and God’s repair. That was one of the best things I’ve read in the past 12 months.”

Find previous editions of “Leading Theologically” here.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.