Author champions the abiding faith of Harriet Tubman

Dr. Tiya Miles, who wrote ‘Night Flyer,’ delivers an inspiring McClendon Scholar program for New York Avenue Presbyterian Church

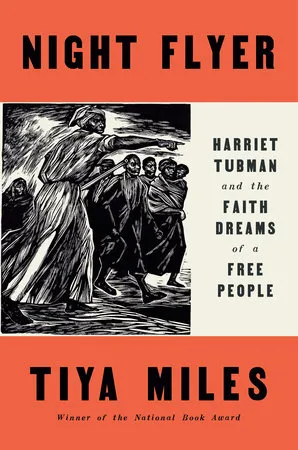

LOUISVILLE — Dr. Tiya Miles set out to write what would become her latest book, “Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dreams of a Free People,” with an eye toward exploring Tubman’s legendary abilities to read both nature and people. “That was the plan,” Miles told a large crowd online and in person at Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, D.C., during Tuesday’s McClendon Scholar program brought by New York Avenue Presbyterian Church.

Instead, “What I saw more than anything else was Harriet Tubman’s deep faith,” said Miles, the Michael Garvey Professor of History and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor at Harvard University. As a small child, Araminta “Minty” Ross, as she was named, was “rented out, leased out, loaned out by the man who owned her. When she was sent far away, Minty prayed,” Miles said. In the second house she was sent to as a forced child laborer, “she was terrified to be in this big house with white people, even to get a glass of milk they offered her. Instead of taking the milk — even though she was thirsty — she would hide herself in the architecture of the home and pray. I saw that over and over again. Minty Ross or Harriet Tubman was always seeking out God.”

“‘Night Flyer’ became a book very much about faith and what had to take shape for Minty Ross to become the person we now know as Harriet Tubman,” Miles said. The “core ingredients of her character” included her “passionate belief in God,” “her view that she was never alone,” her “trust in nature to be with her and support her,” and “her ability to recognize what it was her parents were doing and to see them as models in her own life.”

“I am appreciative for what came together to make this book what it became. It speaks directly and indirectly to our times,” Miles said. “It’s not about the typing I did or the research that went into the book. It’s about something else coming through the book that makes it feel like it’s speaking to our moment. I don’t know what that something is,” she said, “but I’m grateful for it, whatever the message is that Harriet Tubman is allowing me to share with you and bring into our conversation now.”

As a girl, Minty’s forced labor put her in the company of her father, Ben Ross, who had already obtained his freedom. While performing “heavy, heavy labor,” the girl also learned about the natural world. “She later said, ‘I was getting fitted for the work the Lord was getting ready for me,’” Miles noted. That work, of course, included working to free 70 people from enslavement in Maryland and another 700 in South Carolina during a military operation.

The Rev. William Lamar IV, senior pastor at Metropolitan AME Church, then joined Miles for a lively question-and-answer session, asking questions on behalf of those gathered. He asked her, “I wanted to see if there’s more you can say about what Harriet Tubman might say to us in this moment.”

“If Tubman were here today, seeing what we are seeing, I think she would tell us to trust, which is such a difficult thing to do. I don’t know if I could do it, but I can tell you she did,” Miles responded. When Tubman knew hunters were on her trail while operating the Underground Railroad, often “she didn’t know what she would do until she paused and let the message come to her,” as portrayed in the 2019 film “Harriet.”

When she’d pause and wait for a message, “it was dangerous, but people were saved,” Lamar noted. “She waited for knowledge that was not scientific, not found in books.”

As a historian, “I struggled with this,” Miles said. “How could all this happen? It didn’t make sense.” One day Tubman took people in her care into a swamp, “and all of a sudden a nice Quaker man came up in a wagon and said, ‘How can I help you?’ Money would just appear. It happened so many times. … I never could find a way to puncture the mystery of what she did. I can only tell you she said it was from God, and she never lost a single person she was working to help free.”

“I think some of us know how to listen to the source, but it’s muted in our present time. There’s so much noise, and we can’t hear,” Miles said. “We have to open those channels and listen.”

At the same time Tubman was listening to God and reacting in response to what God told her, “she was also a brilliant woman, and I didn’t know that until I started my research,” Miles said. “She knew how to act, and she was an astute thinker. When she said she was hearing from God, I take her at her word. But she was also observing her environment. She understood economics.” When Tubman freed herself for the first time, she traded a quilt she’d made to a white woman in exchange for information about a safe house she could go to. “She had a sharp, perceptive sense of who was around her,” Miles said, “and what she had to do to navigate that environment.”

Lamar asked: How did faith and connections with others provide us with lessons to navigate a just path forward today?

“That’s such an important point. Tubman didn’t act alone. She didn’t act without human companionship,” Miles said. “She was regularly in conversation with others and in the care of others and caring for others.”

When she was poor, Tubman nonetheless relied on God. “People who knew her were astounded she would take in more people. They talked about her as someone who was irrational,” Miles said. “What they didn’t realize was Tubman was never alone. They were part of her care circle. They brough her food and money and helped her realize her vision.”

Lamar noted that today we remember Tubman as a soldier and spy, “but the image I have is an elderly woman in a chair covered in a blanket. What do you see in that image?”

“It’s an iconic image. A positive take is Tubman lived to be a very old, very wise woman. She is settled and clear about herself,” Miles said. “She was self-possessed in a knowledge that goes beyond what we can know.”

The photo was taken shortly before Tubman’s death in 1913. “What we don’t see is she is being photographed on land she owns in front of a home she had built to take care of elderly Black people,” Miles said. “We don’t see the long middle years of her life.” Just about everyone called her “Aunt Harriet,” Miles noted. “I think that can give us inspiration that there will be periods of our life that are Underground Railroad and some days we will be strategist and spy. There are days when we need to acquire land and build and bring people in, and days where we can be the ancestors.”

While Tubman never learned to read and write, she had other literacies, including landscape literacy, Miles said. “She could read the landscape and make decisions about what the landscape was telling her,” she said. Once, as a girl, Minty decided to live in the pigpen with a sow and her piglets for four days.

She could also read people. As an adult riding a train on a rescue mission, she recognized a former master. Thinking fast — there was, after all, a bounty on her head — the illiterate Tubman grabbed a newspaper and pretended to read it. “She knew that he would know the Harriet Tubman who was being hunted could not read,” Miles said. “We don’t know why she didn’t learn to read. My interpretation is she had other priorities. She had a lot to do — running a railroad, the Civil War, saving a community. Learning to read and write takes time, and I don’t know if she was willing to devote that time.”

Returning to Tubman’s faith, Miles said that in her early life, “her faith had to do with what it was like growing up as a chattel child. This faith was powerful. It had deep roots and it was widely shared. I can’t imagine her faith wasn’t influenced by others around her,” her parents prominent among them.

“That term ‘chattel child’ is chilling,” Lamar said.

“It is,” Miles replied.

Miles labeled the ripping open of families “one of the deepest evils of this system.”

“There are legacies of hundreds of years of chattel slavery that we still live with. I know all of you know this — slavery was not that long ago.” We shouldn’t be surprised that there are long-lasting effects, she said. “Afterlives are the psychological baggage and trauma, the economic setbacks, some of the fractures and fissures in relationships and the ways the descendants of enslaved people are positioned on the landscape,” she said. “We have not found a way to untangle these relationships,” and we’re headed backward, she noted.

“It’s a mess we live in right now, and I fear it’s only going to get worse, which is why I’m grateful for models like Harriet Tubman,” she said. “She suffered things many of us could not bear and yet she kept going.”

This book and her previous book, “All That She Carried,” winner of the 2021 National Book Award for Nonfiction, “were akin, and were different than other books I wrote,” Miles told Lamar. “These are books in which I didn’t feel alone while I was writing. Ideas would come, and I couldn’t trace them back.”

“One day, I knew ‘Night Flyer’ would start with a storm. I knew I was talking about coming storms,” she said. “I felt a sense of companionship writing this book and ‘All That She Carried.’ I write in the book [Tubman] was an elusive person. I think she wanted some privacy, and I can respect that. I had the sense of a community feeding into this work. I wasn’t alone.”

“Through the example of her life, we can see how she would have approached the problem of being busy or tired. The way she approached that was to keep pushing through,” Miles said. “One thing I struggled with was the lack of balance — of caring for others over caring for self.”

“Part of me wishes she would have taken time to take care of herself, but part of me is grateful she showed us through her example it’s possible.”

View previous McClendon Scholar programs here.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.