There once lived a woman who wrote award-winning lines of poetry, threw out the first pitch at a Yankees game at age eighty, penned the liner notes for Muhammad Ali’s albumI Am the Greatest!, befriended figures such as Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle, made the front page of Esquire magazine in her seventies, and could be found each Sunday and Wednesday in her preferred pew at church—all while donning her signature uniform of cape and tricorne cap.

Her name was Marianne, and she was a wonder.

Marianne Moore (1887-1972), triple-crowned queen of poetry and tricorne hat wearer, is remembered by many. There are those who pull her story to the present through the reading of her words, all those lines of rhythm, all those phrases and ideas that earned her three laurels: the National Book Award, the Pulitzer Prize, and the Bollingen Prize. But there are also those who remember how she stood and sang in her pew at Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church, those who find, within her poems, echoes of moments shared during worship.

This week marks fifty-three years since Moore’s passing and the subsequent funeral at her home church that was attended by two hundred mourners. Though I’d penned an essay about Marianne in 2022, posted on the PHS blog for Women’s History Month, I was unaware of this anniversary. But thanks to Mr. Edward Moran, I am now a converted Moore-ophile. You can read all about Mr. Moran and his expertise in this Presbyterian News Service article we collaborated on in connection with this longer biological sketch. I am forever grateful to him for sharing with me the connections and details of this woman’s life that make her even more special than I’d previously suspected.

PART I: CHILDHOOD, COLLEGE, CARLISLE

Born in 1887, Moore was raised in the manse of the First Presbyterian Church in Kirkwood, Missouri, where her maternal grandfather, Rev. Dr. John R. Warner, served as pastor. Her father, John Milton Moore, was absent from her life. When the Reverend passed in 1894, Mary Moore moved her small family to Carlisle, Pennsylvania. There they remained, and there Marianne blossomed from age eight to twenty-eight.

Marianne studied hard, graduating from Metzger College—where her mother, Mary, taught—in the summer of 1905 at the age of seventeen. She would attend Bryn Mawr in the fall. Her elder brother John Warner was studying at Yale University; he would go on to become an ordained minister and the chaplain at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. But on summer Sundays in 1905, the family would leave their home at 343 N. Hanover Street and walk six blocks to Second Presbyterian Church to attend service.

Mary being a teacher, and Warner being academically minded like his sister, the Moore family shared a love of the humanities: books, music, art, and the discussion of it all. In 1963, Marianne wrote of this childhood steeped in learning: “We were constantly discussing authors. When I entered Bryn Mawr, the college seemed to me in disappointing contrast—almost benighted.”[1]

Despite this passion for the arts, Moore majored in biology. While she learned of the realm of science, the workings of the animal world, she started writing short stories and poems for the campus literary magazine. It was here, in college, that Marianne first received recognition as a writer. She also met and befriended Hilda Doolittle, who would become a mentor to her (a figure in her own right, H.D. led the Imagist movement, was engaged to Ezra Pound, and was a native of Bethlehem, PA, where her own historical marker rests).

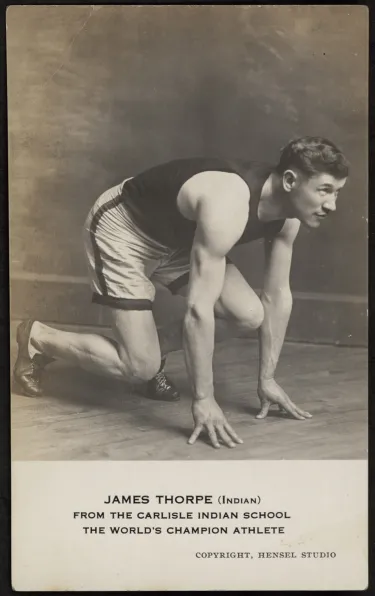

Marianne graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1909, took off on a traveling tour with her mother, and took a teaching position at the Carlisle Indian School upon her return. From 1911 to 1915, she rode her bike to the barracks each morning. One of her students at the institute was Jim Thorpe, who went on to become the first Native American U.S. athlete to win an Olympic gold medal. He won two, both in the 1912 summer games. In 1954, the year after he passed, the famed athlete was laid to rest in Mauch Chunk, PA—which changed its name to Jim Thorpe forthwith.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was one of many such institutions founded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the end goal of forced cultural assimilation. From its inception in 1879 until its closure in 1918, over 10,000 children from 140 Native American tribes were enrolled at Carlisle. Students were banned from speaking their Native language, and emphasis was placed on the disregarding and discontinuing of traditional Native practices. These places of education were typically funded by the federal government, though many were sponsored by religious denominations, the Presbyterian Church included.

In recent years, the policies and practices of these schools—and the US government, which built them and kept them running—have been openly and widely condemned, and investigative research projects have unearthed the true, and often dark, histories of these schools. This process was spearheaded by the U.S. Department of the Interior, whose secretary announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in June of 2021. There have been hundreds of articles and media pieces discussing the findings and bringing the cruelty of these places to light, including one headline from July 2024 that reads “Federal Investigation Finds At Least 973 Children Died in Indian Boarding Schools.” At PHS, we’re working on investigating our collections, too. One of our first projects was the repair of the Tucson Indian Training School records. Though much work has been done, there are still so many stories to unearth—and, thankfully, there are many who are dedicated to digging for them. You can find out how the legacy and struggle of Carlisle Indian Industrial School students is being honored through the Carlisle Indian School Project.

The connection between Moore and Thorpe goes even deeper, when one realizes that they were born just months apart, and both in the western US. Edward Moran takes these connections into account and winds the two stories together in his poem “Marianne Moore Grows Up.” The poem is separated into three parts—1910: Marianne Moore Instructs James Thorpe at the Carlisle Indian School; Palm Sunday, 1935: Marianne Moore and her Mother Join the Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church; 1980: I Buy a House in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania That Used to Belong to Bessie Moore. This excerpt from part one also makes mention of Marianne’s father.

There were at least three births that year:

Marianne's in Kirkridge, in November,

and, in May, the twins, James and Charlie Thorpe,

in the Indian Territories (later Oklahoma).

James was sent back East (only he, not Charlie, survived)

To Pennsylvania, to the Pratt-model school, not overly far

from Gettysburg, where Rev. J. Riddle Warner and his bride

Jennie Craig, had nursed the war-wounded in '63, she'd

died of typhus and left a daughter in Riddle's care, he raised her in Missouri and married her to John Milton Moore,

a gearloose inventor, who went mad, bust, and broke

leaving dreams of smokeless furnace up in smoke,

but not before two attempts at carrying on:

Rev'rend John Warner Moore and sister Marianne

(guardians of both poem and sermon)

And I must add "my own father, full of craze, amen."

The final stanza (and my personal favorite) reads:

It is the confluence of poet and athlete

of sinew and dactyl

of pentathlon and pentameter

of missionary spirit that made America, my America

where I have my stone house.

and of my father and of my hearth the stone

and of James the runner and of Marianne the muse

and of the dust and the scythe

and the grass

When asked about Thorpe, who she watched excel in the classroom and on various sports fields (football, track, baseball), Marianne remembered him as being a gentleman. “He was a gentleman. I called him James. It would have seemed condescending, I thought, to call him Jim.”[2]

A few years after her teaching stint at Carlisle, Marianne and her mother would leave Carlisle for New York, the state that they called home until the end of both their lives. Their presence in Carlisle, however, has left quite a mark. Literally—there’s a historical marker at 343 N Hanover Street, where they lived, dedicated to Marianne. It reads: Eminent Poet, editor, essayist, and teacher. Her independent spirit and keen eye for detail distinguished her life and work. Moore won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature, the Bollingen Prize in Poetry, and the National Book Award. She lived here (1896-1916).

PART II: LIFE & DEATH IN THE BIG APPLE

In 1918, at the age of thirty-one, Marianne moved with her mother to New York, New York. It had been three years since her poems first appeared in publications. In the Big Apple, she turned her direct focus toward the craft of poetry and literary criticism—while also leaving herself time to attend baseball games, work at the New York Public Library, and fraternize with folks like e.e. cummings and William Carlos Williams.

She began to truly make a name for herself, participating in literary circles and contributing to the Dial literary journal, of which she became acting editor from 1925 until its discontinuation in 1929. Throughout the harsh years that followed the fall of the stock market, Moore supported herself and her mother with her poetry and reviews. In 1935, the two women joined the Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn. Mary Warner Moore died in 1947, and Marianne attended services regularly until her death in 1972, penned poems directly inspired by her faith, and was a beloved member of her church community.

Remember that one of Marianne’s passions was the animal world? She penned a series of poems over the course of the late 1930s packed with scientific detail and notes about the creatures she’d encountered in her research. She utilized stories of animal survival, adaptation, and behavior to draw out moral lessons in her poetry. Themes of independence, honesty, and the connection between art and nature weave through her lines. In 1936 she published the collection The Pangolin and Other Verse. From the titular poem:

Another armored animal – scale

lapping scale with spruce-cone regularity until they

form the uninterrupted central

tail-row! This near artichoke with head and legs and grit-equipped gizzard,

the night miniature artist engineer is,

yes, Leonardo do Vinci's replica –

impressive animal and toiler of whom we seldom hear.

Pangolins are not aggressive animals; between

dusk and day they have the not unchain-like machine-like

form and frictionless creep of a thing

made graceful by adversities, con-

versities. To explain grace requires

a curious hand.

In 1951, Moore’s Collected Poems won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Two years later, she received another award, the Bollingen Prize. At this time, and throughout the remainder of her years, Marianne became something of a popular figure—known for her eccentric style, her unwavering and unconditional love of the game of baseball, and her talent at weaving prose, she was often spotted attending public events and spending time with other big names, like boxer Cassius Clay/Muhammad Ali, who she was pictured with in 1963. In 1966, she appeared on the cover of Esquire magazine alongside seven others—Joe Louis, Norman Thomas, Helen Hayes, John Cameron Swayze, Kate Smith, Eddie Bracken, and Jimmy Durante—and a note that “42 others” could be found on page 84. The theme of the issue was, “In a time where everybody hates somebody…nobody hates The Unknockables.”

In 1968, eighty-year-old Marianne attended a Yankees game, where she threw the opening pitch. The moment inspired a column titled “Poetry in Motion,” penned by Larry Merchant of The New York Post. In the article, Merchant writes that, for Marianne, to be asked to throw the first pitch was “an honor she deems more astounding than all the honorary degrees and poetry prizes bestowed on her.”

Then-owner of the New York Yankees Mike Burke—who would be one of the 200 mourners present at Moore’s funeral four years later—had gifted her a fielder’s glove and two baseballs, “to work out the kinks.” She’d played, long ago, as a left fielder. Her brother, Navy Chaplain John Warner, would be serving as her catcher. “My brother said I should return the glove after the game, but I’m going to keep it,” Moore told Merchant. “Whenever I feel gloomy I watch a game,” she added. “The people aren’t sheep. The grass is so green.” It comes as no surprise that she’d also taken to poetry to express her love for the game. Here are a few lines from her poem, “Baseball and Writing”:

Fanaticism? No. Writing is exciting

and baseball is like writing.

You can never tell with either

how it will go

or what you will do…

Four years after tossing the first pitch at Yankee Stadium, Marianne Moore, age eighty-four, passed from this world to the next. From the February 9, 1972, New York Times article recapping the procession the day before, we learn the details of Marianne’s funeral. “Final honor was paid yesterday to ‘our beloved Marianne’,” the piece begins, “at funeral services in the Brooklyn church she had attended for 34 of her 84 years.” After a private service for the family concluded, a group of 200 mourners gathered in the pews of Lafayette Presbyterian, “reflecting the catholicity of Miss Moore’s friendships. The mourners included blacks and whites, the very elderly and the young, relatives, long-time friends, educators, literary persons, booksellers and, of course, baseball personalities.”

Dr. Knight, the presiding pastor, decided to enumerate upon that ‘side of her character and life about which she was extremely reticent, and appeared to some to be diffident…her personal faith,’ rather than add to the bounty of praise already accorded the prize-winning poet.

Before her passing, Moore sold her personal and literary papers to the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia. She left the institution, written into her will, all her furniture and belongings, too. The museum has recreated her Greenwich Village living room as part of their permanent display—though the Marianne Moore Room is currently closed for updates through March 2025. If you stop in when they reopen, we hope you get a glimpse at one of her tricorne hats.

Marianne lives on in the hearts and minds of so many. Those she touched personally—her fellow congregants at LAPC, her family members, her students—and those who study her words and legacy and feel close to her through the art she’s left behind for us.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This profile was pieced together with information gathered from stories and documents offered up by Mr. Moran as well as resources I endeavored to access on my own. Without his interest, insight, and passion, I would not have been able to craft such a complete picture of Marianne. Mr. Moran has all of my gratitude.

RELATED READINGS

“Hidden Carlisle: Where Marianne Moore Walked,” by Jeff Wood

Marianne Moore Historical Marker: Behind the Marker

"The Students of Marianne Moore: Reading the ugly history of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where the poet taught", by Siobhan Phillips, Poetry Foundation, March 14, 2017

"Washington Post reporter explains how they uncovered more Native children deaths at boarding schools", by Melissa Olsen, MPR News, December 24, 2024

Carlisle Indian Industrial School Resource Center

[1] “Hidden Carlisle: Where Marianne Moore Walked,” Jeff Wood, Dickinson.edu.

[2] Poetry in Motion, Larry Merchant, The New York Post, originally published 1968.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.