In October 2017, Presbyterians will celebrate the 500th anniversary of a pre-digital tweet storm: Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. The theses, which criticized the sale of indulgences by church officials, are considered the opening salvo in the Protestant Reformation, a movement that emphasized individual relationships with God and salvation through faith alone.

Luther was an early adapter of the printing press—the social media of the sixteenth century—and the most widely shared writer of his time. After the 95 Theses, which legend has it he nailed to the doors of Wittenberg’s All Saints Church in 1517, Luther’s translation of the Bible into German is his most consequential work. He began the translation in 1521, encouraged by Philipp Melanchthon, a professor of Greek and theology at the University of Wittenberg where Luther also taught. A vernacular Bible translation was central to Luther’s radically democratic theology, which emphasized the primacy of Scripture and called for its availability in common languages.

Luther's 95 Theses nailed to the doors of Wittenberg’s All Saints Church, engraving ca. 1850. Islandora ID: 8788.

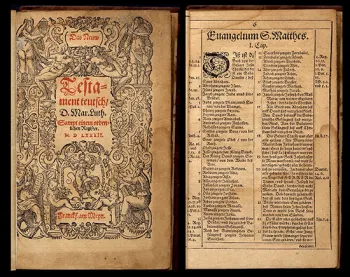

German translations of the New Testament existed prior to Luther’s version, but those referenced the Latin Vulgate—the official Bible of the Catholic Church which Luther criticized in his Theses. Desiderius Erasmus had published a 1516 New Testament in Greek and Latin, a work Luther used to translate his New Testament into German. First printed in September 1522, the “September Testament” does not include Luther’s name on the title page, an elision meant to limit church reprisals. A year earlier, after being condemned by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and excommunicated by Pope Leo X, Luther had taken refuge in Germany’s Wartburg Castle.

Translating the Old Testament from Hebrew proved far more difficult than Luther’s work with the New Testament. Wars, illness, and a lack of expertise in Hebrew slowed his progress to a virtual crawl, as did his insistence that the translation be relatable to all Germans. In his 1530 “Letter on Translating,” Luther contended that the German translator “must not be led by the Hebrew words; he should make sure that he really understands the sense and ask himself: ‘What would the German say in such-and-such an instance?’”

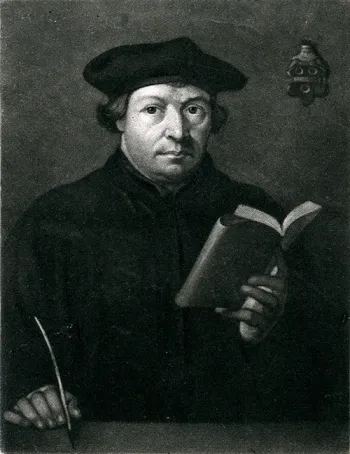

Portrait of Martin Luther by John Sartain, engraving 1835. Islandora ID: 8844.

Luther was an experiential researcher, visiting local marketplaces in disguise to learn how ordinary Germans spoke. The application of his editorial philosophy led to some inventive interpolations. In the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible, he replaced the word “chameleon,” which would have been unknown to sixteenth century Germans, with “weasel.” It took Luther and a team of fellow scholars—including Melanchthon and Matthäus Aurogallus, a professor of Hebrew—twelve years to translate and publish the entire Old Testament. An abiding struggle was making the Old Testament prophets sound German. As Luther wrote, “We have often spent a fortnight, or even three or four weeks, over a single word….Now that it is finished anybody can read it easily and smoothly….Little does [the reader] realize how we sweated and strained to remove those obstacles.” The Pentateuch appeared in September 1523, and publication of the prophet books soon followed. Luther lectured at the University of Wittenberg based on his translations. German printers published many of his lectures.

Luther’s New Testament in German. Above issue printed in Frankfurt, 1582.

The first complete Luther Bible was printed in 1534, including the Old and New Testaments and the Apocrypha. Luther did not think the Bible’s books equally important—those that emphasized Jesus Christ he deemed authentic scripture; others (such as Revelation) he subordinated. While some criticized Luther for his textual relegations, others attacked him for editing passages to fit his preferred theology. Despite such criticisms, many German readers regarded his Bible as a work of literary genius, the way English readers would come to revere the King James Bible in the seventeenth century. Luther’s Testaments had a lasting impact on German letters, popularizing the Saxon dialect as a standard regional vernacular.

As with the 95 Theses, the printing press helped to make Luther’s Bible a popular success; a single Wittenberg publisher created 100,000 copies between 1534 and 1574. Luther’s work went on to inspire other Biblical translations across Europe, including those in English by William Tyndale (“The Great Bible”) and Myles Coverdale (“The Geneva Bible”), the latter of which the Puritans would bring to America.

--

PHS holds editions of Reformation Bibles. Find images about the Protestant Reformation using our online archives: www.history.pcusa.org/pearl. Download the church bulletin insert "Luther's Bible" from our Reformation Sunday page.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.