Looking for Hope, and Finding It

A Letter from Cindy Corell, mission co-worker serving in the Dominican Republic

Subscribe to my co-worker letters

Dear friends,

It was the third day of school, and Wenchanaika dropped her head to her right shoulder. The rest of the students — except the two boys at the corner of the table pushing one another — were watching the teacher. All the action, the teacher’s handclapping and questions kept Wenchanaika’s attention for a bit, but a nap seemed like a good idea.

That’s how it looked to me, at least. Like this tiny girl, I didn’t understand much of what the teacher said either. Spanish is a new language for us both. But Wenchanaika is five years old. Last year she was in school across the border in Haiti, and here, everything felt different.

I moved to Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, in late July. After more than four years in the U.S., I was finally back on the island of Hispaniola, but on the eastern side. I had lived in Haiti for seven years, and I have a lot to learn.

This visit to Basica Escuela Rural at Estrella Vieja near Monte Plata was an unexpected treat. I was in Monte Plata to visit folks from Juventud Empoderada Para la Transformacion (JET) or Youth Empowered for Transformation (its English translation), the group of mostly young people helping others. Much of their work concerns supporting immigrants from Haiti, some even from generations ago, who have not been able to acquire Dominican documents. Through JET’s executive director Saturnino Perez, I’ve learned how a 2013 Dominican Supreme Court decision tangled the ability of those from Haiti to navigate the immigration system. Caught between two nations, many folks in the Dominican Republic struggle with neither Haitian nor Dominican documents. Education, health care and development opportunities are often out of reach and deportation is a daily threat.

Tensions between neighbors Haiti and the Dominican Republic run deeply. As someone who cut her international mission teeth in Haiti, I knew living on the other side of the border would challenge me. A new language and a new culture are enough of a challenge. Remaining open to all sides of a controversy adds another layer of difficulty.

On my second day in Monte Plata, I was invited to the school in Estrella Vieja by Perez’s wife, Dorca Perez, who is an administrator there. Several students don’t speak Spanish if at all. It would be a chance for me to speak Kreyòl and better understand rural schools in the DR.

The day before I had visited a batey, a neighborhood mostly made up of people of Haitian descent. Some have lived here for generations while others are relative newcomers. About a dozen women and men talked about whether an agricultural project could work in their community.

Perez facilitated the conversation in both Spanish and Kreyòl. A woman from a nearby house brought us cups of hot coffee. I listened to their words, the way they joked with one another, and, on occasion, disagreed.

I sensed hope.

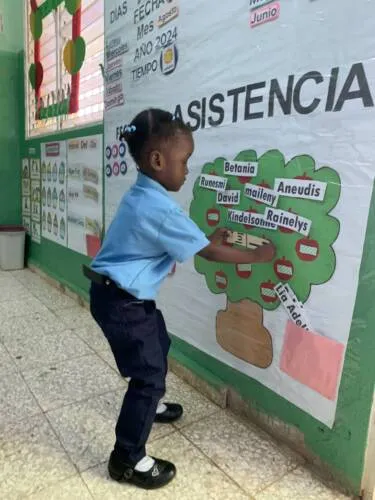

The next day at the elementary school I felt the same. Second graders fussed about having to settle in their seats. Kindergartners were eager to help paste signs to the wall. Fourth graders offered ways they can make their classroom a more civil place.

“Ask before leaving your room.”

“Let everyone else have a chance to talk.”

“Respect other students and the teachers.”

As they called out their ideas, a teacher wrote them on the whiteboard.

Conditions are difficult for so many on both sides of this island. Poverty is real. Relations in some places are very strained. Political rhetoric often takes precedence when we try to define a nation. I’ve only been in the Dominican Republic for a few weeks, but I’m reminded again that governments aren’t people.