Sacred Spaces

Building Communities of Faith Page 1

“For where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them.”

—Matthew 18:20

We often associate worship spaces with gothic cathedrals, steeples, bell towers, and stained glass windows. But throughout history, the need for traditional worship spaces has been challenged—both out of necessity and in an effort to seek a more intimate connection with God. Many church communities began in temporary, makeshift dwellings, private homes, or in “the open air."

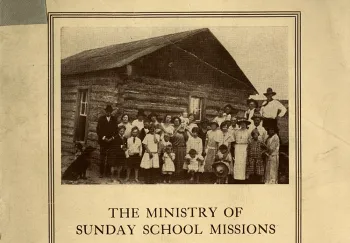

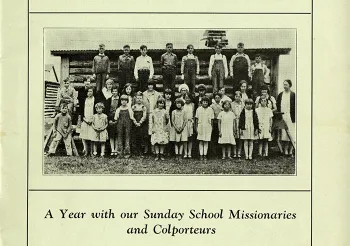

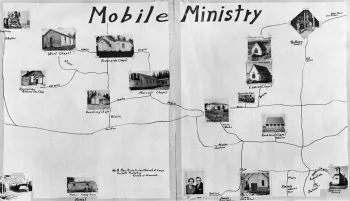

The erection of churches has been linked to the missionary enterprise since the founding of Presbyterianism in America. While the national church could offer few financial resources to help small communities build new church structures, it extended its reach by enlisting Sunday school ministers and mobile ministers, who traveled the country to find communities in need. Mobile ministers have found success among diverse communities across the country—lumberjacks in the Pacific Northwest and cowboys and ranchers in the Southwest are just two of many examples. The ministry of mobile missionaries often led to the erection of the first Presbyterian church building in a community, which the minister built alongside residents.

All images appearing in this exhibit are sourced from the society's collections.

The Origins of Mobile Missions Page 2

“Most Presbyterian churches that are over a hundred years old were once rural churches….Their earliest roots may have been in the newly-turned earth of a well-nigh trackless wilderness or between the corn-rows of some fertile field….The pastorate of a single minister has been long enough for one certain village church of a hundred members to become a church of over three thousand members in a city of over 150,000 population.”

-Herman N. Morse, The Rural Mission of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.

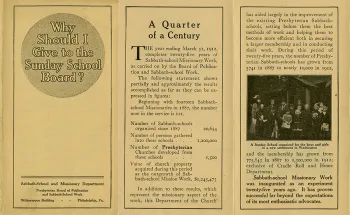

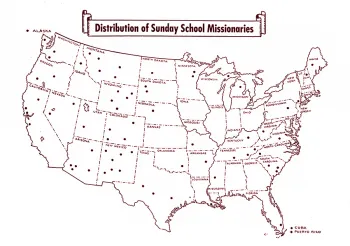

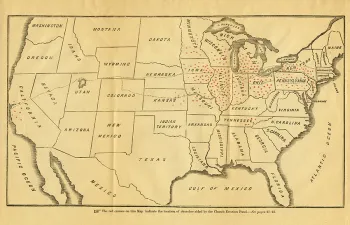

The work of mobile ministers emerged from the Presbyterian Board of Publication, established in 1839 with an aim toward growing Sunday school ministries. In 1887, as the work of Sunday school ministers increased, the board was renamed the Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work. Within 25 years, Sunday school missionaries had established at least 1,500 new churches in remote, rural areas across the country. After it became apparent that their work fell more in line with the national mission work of the Board of Home Missions, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. General Assembly transferred the agency to the newly reorganized Board of National Missions in 1923.

The Board's original goal to reach individuals living in remote areas naturally meant that Sunday school mission work began in rural areas. In The Rural Mission of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., Herman N. Morse discusses the rural roots of mobile ministry work.

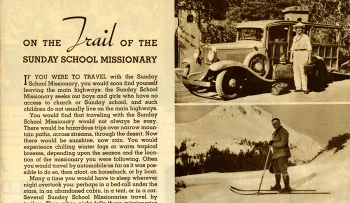

The work of Sunday school missions gradually came to encompass a more inclusive form of ministry—mobile ministries. While Sunday school ministers educated and evangelized children in remote areas, mobile ministers reached out to adults, children, and families who were either physically or spiritually alone.

Traveling from one remote dwelling to the next, mobile ministers spread the gospel and performed marriages and baptisms.

The Cowboy Preachers Page 3

“The most sacred place of the heart is the place of prayer. If we would only pray – out under the stars – in the heat of the day – in the cool of the day – in the city – in the home – in the desert – in time of trouble – in time of health – at all times ... how helpful it is to climb the hill, to get out under the stars, to meet and mingle with other people.”

—Roger B. Sherman, “Sacred Places of the Heart.” Sermon, 1962.

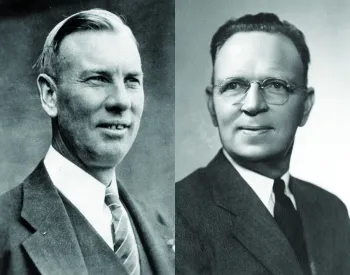

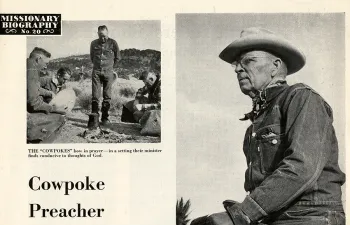

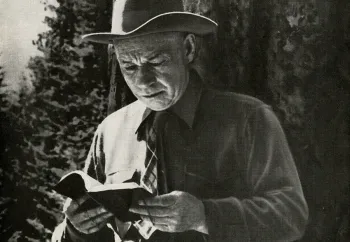

To the cowboy and ranch families living far out in the remote landscapes of the American Southwest, Presbyterian mobile ministers Ralph J. Hall (1891-1973) and Roger B. Sherman (b. 1892) were legendary men. They eschewed the pulpit for the saddle and preferred to meet their congregants under the stars rather than within a church building.

Often traveling hundreds of miles on horseback, they would arrive on the doorsteps of families so isolated they had never stepped foot inside of a church, read a Bible, or heard a sermon. After arriving in a new community, they worked tirelessly among the cowboys and ranchers, rounding up and branding their cattle, to earn a place in their small communities. Though they erected many chapels, churches, and church schools, their most enduring work lives on through the communities they established outside of traditional church structures.

View the short film Little Cowboy Americans, the story of Rev. Ralph J. Hall (1891-1973), Rev. Roger B. Sherman (b. 1892), and Sunday school missions in the American Southwest. Presented by the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Board of National Missions, 1945.Before becoming a minister, Ralph Hall was, first and foremost, a cowboy. Raised on a cattle ranch in the western plains of Texas, he understood the loneliness that came with ranch life and found inspiration in the work of a traveling minister who arrived one day on his family’s doorstep.

When the residents of his little town crowded inside a schoolhouse to hear the minister’s sermon, “there was a spirit of awe and reverence about it all” that he never forgot. Hall dreamed of becoming a missionary for the Presbyterian Church but an eye condition discouraged him from pursuing a seminary education. Soon after he left home at the age of eighteen to become a lay missionary, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Presbytery of El Paso became aware of Hall and realized that his inability to baptize or provide communion services was a hindrance to his work. The presbytery ordained him in 1916, and in 1925, he was appointed the synodical missionary for the entire state of New Mexico. By 1940, he was the supervisor for all Sunday school missionary work west of the Mississippi River.

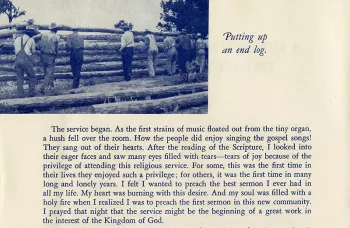

In A Sunday School Missionary’s Dream That Came True, Ralph Hall describes his work in Lindrith, New Mexico, which led to the building of a church, manse, and health center there.

Roger Sherman was raised on a ranch in Lubbock, Texas, where he and Ralph Hall later met and formed a lifelong friendship. Hall converted Sherman and convinced him to become a lay minister for the Presbyterian Church. In 1929, Sherman began missionary work in Nevada. Two years later, the Presbytery of Pecos Valley transferred him to New Mexico, where he worked side by side with Hall. Despite never finishing high school or pursuing seminary training, the presbytery ordained him in 1939.

In 1948, Sherman acquired a permanent ministry at the First Presbyterian Church (now Community Presbyterian Church) in Magdalena, New Mexico, a church which he helped to build.

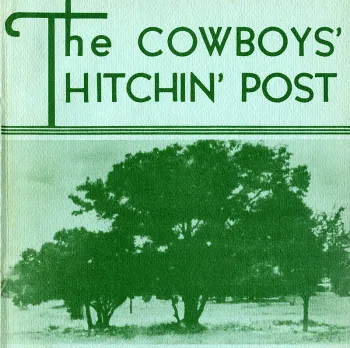

On January 1, 1940, Ralph Hall, R. Everett King (Director of the Department of Sunday School Missions), and cowboy Joe Evans met in the Hotel Del Norte in El Paso, Texas, to plan the first Ranchmen’s Camp Meeting: an event featuring guest preachers, Bible study, singing, and meals cooked over a fire.

They based their idea on the Bloys Camp Meeting, founded in 1890 by Presbyterian minister William B. Bloys (d. 1917) and held in the Davis Mountains of Texas ever since.

After scouting the New Mexico landscape for a location, they settled on Nogal Mesa—a beautiful high pine mountain site near Carrizozo, New Mexico. Despite the lack of water on the mesa, little money for food or supplies, and no advertisement beyond word of mouth, the meeting was a huge success. By 1964, camp meetings were formed in six states and attendance exceeded 20,000. Though sponsored by the Presbyterian Church, camp meetings were and remain interdenominational.

Parish in the Pines Page 4

“In all the country there is scarcely a more interesting group of men—interesting because so wayward and prodigal in life and habit, while their forest home appeals to every leaf-loving soul. They are the nomads of the west—farm hands and railroad constructionists in the summer, woodsmen in winter—with no settled abode, no place they call home.”

—Thomas D. Whittles, The Lumberjack Sky Pilot. (Chicago: Winona Publishing Co., 1908.)

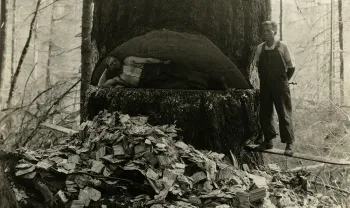

At the turn of the twentieth century, the harvesting and transporting of trees remained a traditional business that necessitated the use of hand-tools and men capable of enormous feats of physical strength. The men who sought out this type of work in the frontier regions of the United States often labored under fierce weather conditions, faced extreme danger from falling trees, and led uncertain, migratory lives, following jobs from state to state and living in company-run bunk houses on the far outskirts of towns.

Although lumberjacks were romanticized for their rugged individualism and heroic masculinity, they were also maligned for their heavy drinking and bawdy, uncivilized behavior. Living in isolated areas, loggers often spent their free time and meager earnings in gambling houses and saloons. Most gave little thought to attending church and were deeply skeptical of roving preachers.

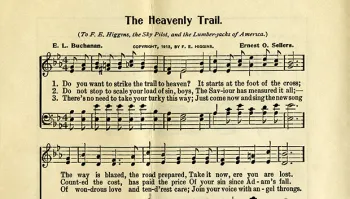

But to the lumberjacks working in the forests of northern Minnesota, Presbyterian minister Frank E. Higgins (1865-1915) was affectionately known as the “lumberjack’s sky pilot” because he guided their wayward souls toward heaven.

Brought up in a family of homesteaders in Shelburne, Ontario, Canada, Frank E. Higgins was accustomed to the toil and hardship of frontier life from an early age. Although he dreamt of becoming a minister from boyhood, running the family farm left Higgins little time for schooling, a failing that he would try to remedy for much of his life in order to qualify for ordination. Higgins preached his first sermon to the lumberjacks in 1895. Accompanying a member of his congregation to a log drive at Kettle River, he was surprised when the lumberjacks asked him to deliver a sermon.

That day marked the beginning of a ministry that would make Frank Higgins a national figure and one of the best known logging missionaries in the United States. In 1902, after several years of preaching to the lumberjacks in his spare time, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. made Higgins a full-time missionary. In 1908, the Board of Home Missions appointed him Superintendent of Lumber Camp Work. By 1912, he had established logging missions in Washington, Oregon, Arkansas, and the Adirondacks modeled on his work in Minnesota. Acting on the conviction that a missionary should be one with the people he is serving, Higgins won the loggers’ respect with his willingness to work alongside them and his informal yet dignified style of preaching.

As demand for Frank Higgins’ work in the lumber camps grew, he began to recruit additional sky pilots to carry out his mission. One of the men to follow him into the mission field was Richard Ferrell (1855-1956), an ex-prizefighter and blacksmith who experienced a religious conversion after hearing Rev. John Timothy Stone (1868-1954) preach at the Fourth Presbyterian Church in Chicago, Illinois.

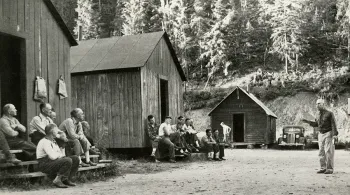

Like Higgins, Ferrell lacked a formal education and gained acceptance among the lumberjacks by working alongside them. In 1914, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Board of Home Missions commissioned Ferrell to do logging camp work in the panhandle of northern Idaho. Eventually, his parish would extend to eastern Washington and to a portion of western Montana.

By the 1940s, the nature of lumber work changed in the United States. Instead of living in temporary housing, loggers took up permanent residence with their families in nearby towns and commuted to work by automobile. Ferrell’s responsibilities also evolved. On top of his regular duties of preaching the Gospel and bringing religious tracts to the men, he began to perform marriages, baptize the lumberjacks’ children, and establish Sunday schools in isolated school houses and abandoned camp grounds.

Originally ordained by the Mennonite Brethren Church, Herbert M. Peters (b. 1904) was received as minister in the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (PCUSA) by the Presbytery of Duluth in 1948. That same year, he began a full-time career as a Sunday school missionary to lumberjacks and miners in northern Minnesota under the PCUSA Board of National Missions.

At that time, the area under the Presbytery’s care consisted of many sparsely settled communities, the inhabitants of which could not always reach an organized church. To bring these small communities together under a single ministry, the Presbytery granted Rev. Peters permission to organize the North Pine Presbyterian Church at Large in 1955. The organization of the church included a building program to erect chapels in various logging areas. Much of the timber used in the construction of the chapels was cut and sawed by lumberjacks who would later worship in the buildings.

Building Presbyterian Worship Spaces Page 5

“It is hard for those who have always worshipped in comfortable sanctuaries to understand the discouragements under which a church without a house of worship labors, and the difficulties which beset its first attempt to secure a sanctuary.”

—Annual Report. (St. Louis: Church Extension Committee of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Old School, 1856).

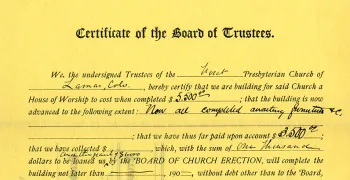

Prior to 1844, the design and construction of churches in the United States was regarded as a local responsibility, with the Presbyterian Church dispensing very little aid to financially weak congregations seeking suitable houses of worship. Fledgling congregations out on the Western frontier felt this lack of support most strongly, because their members were often too poor to finance the construction of comfortable sanctuaries. As a result, services were commonly held in temporary dwellings, such as barns, distilleries, schools, private homes, or in the open air. When more permanent accommodations could be obtained, they were often simple, rudimentary structures, such as log houses. To build anything more substantial, a struggling congregation risked falling into debt, and many often did.

Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (Old School)

The 1844 General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (Old School) directed the Board of Missions to appoint a Church Extension Committee to aid feeble congregations in building suitable houses of worship. Eleven years later, the General Assembly created a new Church Extension Committee, directly responsible to the assembly itself. Headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, the new committee was positioned near the frontier where most of the aid was to be extended. In 1860, the assembly elevated the status of the committee to that of a board.

Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (New School)

In 1853, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (New School) appointed their own Committee on Church Erection, which reported directly to the General Assembly. The committee immediately initiated an ambitious campaign to raise $100,000 in building funds, which were used to issue interest-free loans and occasional small grants to New School churches. In a majority of cases, the committee dispensed aid to feeble congregations occupying simple, one room structures. Like the Old School Church Extension Committee, the New School committee rarely subsidized the full cost of building a house of worship. Believing that church members should raise most of the funds, the committee’s main objective was to help congregations with the remainder of the cost and to prevent them from falling into debt.

Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.

In 1870, the New and Old School church extension agencies consolidated their work in a new organization known as the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Board of the Church Erection Fund. Contributions from PCUSA churches largely funded the board, although some money was obtained through individual gifts and the sale of donated land.

Despite the board’s many successes in securing sanctuaries for struggling churches, the number of “unsheltered” congregations in need of urgent aid far surpassed the number the board was able to assist. As a result, the board made regular appeals to the denomination’s self-supporting churches, reminding them to contribute to its benevolent work.

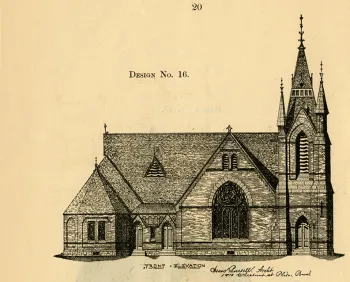

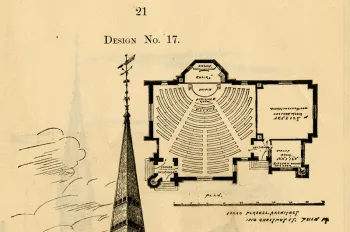

In 1875, the board provided an additional service to congregations by publishing church designs along with its annual reports. The designs included many examples of smaller, less expensive buildings as suggestions for congregations embarking on church erection projects with limited funds. By 1920, the board had assisted nearly 12,000 congregations to build churches or manses. In 1923, the work of the Board of the Church Erection Fund became the responsibility of the new Board of National Missions.

The catalog includes two designs by Philadelphia-based architect Isaac Purcell (1853-1910):

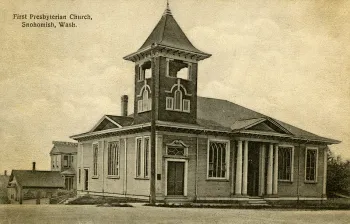

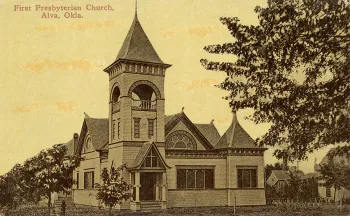

The following churches were just two of those that received aid from the PCUSA Board of the Church Erection Fund for the construction of their buildings.

United Presbyterian Church of North America

The Board of Church Extension is one of the original boards of the United Presbyterian Church of North America (UPCNA), organized in 1859 by the first General Assembly. The purpose of the Board of Church Extension was to aid mission stations and congregations in obtaining suitable houses of worship. It also gave aid in the erection of parsonages. Over the years, the work of church extension was directed by the Board of Home Missions and later the Board of American Missions. Following the merger of the UPCNA and the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. in 1958 to form the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (UPCUSA), the work of the Board of American Missions was placed under the Board of National Missions of the UPCUSA.

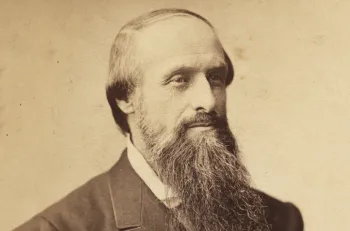

Rev. Dr. John T. Pressly (1795-1870) served as the president of the Board of Church Extension and had charge of the work until the election of a corresponding secretary in 1870.

Presbyterian Church in the U.S.

In 1885, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (PCUS) authorized the Executive Committee of Home Missions to make loans to congregations to aid in the building of churches. These loans were to be paid back in installments, without interest, running from one to five years.

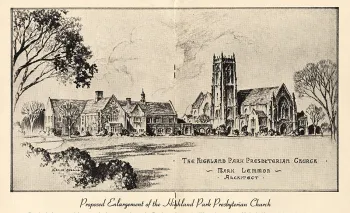

The Executive Committee of Home Missions sought to promote new church enterprises in new communities, particularly in the suburbs and sub-divisions of growing cities. The Highland Park Presbyterian Church in Dallas, Texas, is an example of this type of investment. In 1926, the committee donated $10,000 toward the establishment of this church. At the end of the 1943-1944 church year, the Highland Park Presbyterian Church reported a membership of 2,111.

Rev. Dr. John N. Craig (1831-1900) served as the secretary of the Executive Committee of Home Missions from 1883 until his death in 1900.

The PCUS Board of Church Extension organized a Department of Church Architecture in the 1960s to provide information, rather than funding, to congregations undertaking building programs. The department was closed in 1973.