Presbyterians and the Civil War: Witnesses to a Great Moral Earthquake

Presbyterians and the Civil War Page 1

In the mid-nineteenth century, theologians debated the scriptural justifications for or against slavery, and Presbyterians in America thought deeply about their own beliefs. The conflicts they faced would be magnified in the violent division of the nation, the Civil War. The Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., after splitting into the Old School and New School branches in 1838, splintered further in 1861 over political issues, including slavery.

These soul-wrenching challenges prompted the Reverend H. M. Painter to declare in a sermon:

"We are in the midst of one of those great moral earthquakes, so graphically described by our Saviour: there shall be distress of nations, with perplexity; the sea and waves roaring, men's hearts failing them for fear, and for looking after those things which are coming on the earth."

While the Civil War is an account of division on the one hand, on the other hand it is a story of Presbyterians coming together to care for soldiers and others directly involved in the war. Women and chaplains contributed much to the support of troops. Presbyterians additionally fulfilled their spiritual duties by providing assistance to freed slaves.

"Presbyterians and the Civil War: Witnesses to a Great Moral Earthquake" (first shared in 2014) uses sermons, manuscript diaries and letters, published materials, prints, and photographs to share the stories of American Presbyterians during this time of crisis. You can find more resources about Presbyterians and the Civil War here.

Theological Aspects Page 2

Presbyterians from both the North and the South used biblical quotations and theological arguments to justify why they were fighting the Civil War. Scripture also served as a source of strength, inspiration, and consolation for those forced to endure hardships during the war.

Debate Over Slavery

Decades before 1861, the Presbyterian church had divided over slavery. In 1838, the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. split into the Old School and New School factions partially over the issue of slavery and abolition. Sermons of the time ranged from extolling slavery as a divine right to condemning it as a moral sin.

In 1845, Presbyterian pastors, Rev. Jonathan Blanchard (1811-1892) and Rev. Nathan Rice (1807-1877), held a four-day debate on the question “Is Slavery Itself Sinful, and the Relation between Master and Slave, a Sinful Relation?” A member of the New School, Blanchard debated the affirmative.

"Thus slave holding is degrading men to the level of brutes as completely as the nature of the case will admit." (Blanchard, A Debate on Slavery, 46)

The Anti-Slavery Society, based in New York City, published monthly The Anti-Slavery Record. Arthur Tappan (1786-1865), a Presbyterian, and William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) founded the abolitionist group in 1833.

The overzealous language and tactics of some abolitionists brought about criticism from certain ministers. Henry Van Dyke (1822-1891) was a Presbyterian minister of the Old School branch. In an 1860 sermon, he stated that slavery was a necessary step in bringing Africans towards Christianity and that abolitionists were dividing the country.

“I am here to-night, in God’s name, and by his help, to show that this tree of Abolitionism is evil, and only evil—root and branch, flower, and leaf, and fruit; that it springs from, and is nourished by, an utter rejection of the Scriptures; that it produces no real benefit to the enslaved, and is the fruitful source of division and strife, and infidelity, in both Church and State.” (Van Dyke, The Character and Influence of Abolitionism, 7)

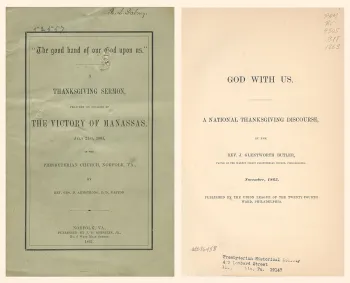

Thanksgiving Sermons

Rev. Dr. Andrew H. H. Boyd (1814-1865) delivered a Thanksgiving sermon on November 29, 1860, just months before the war broke out. In his sermon, Boyd discussed his fears of what might result from the disagreements over “the peculiar institution” of slavery. While he viewed the North as an instigator, he hoped political compromise would continue to preserve the Union. Towards the end of the war, Boyd was imprisoned at Fort McHenry in Maryland for being a Confederate sympathizer.

“. . . Let us render to Him the sincere thanksgiving of our hearts; let us before His altar this hour, purpose to do our part to strengthen, by all legitimate means, the ties that should bind together every part of this Union. . .” (Boyd, Thanksgiving Sermon, 20)

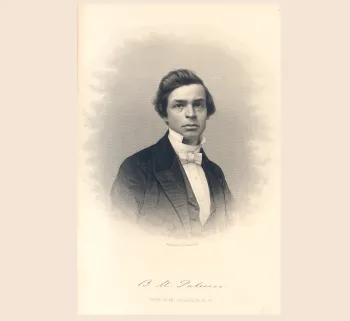

Rev. Benjamin Morgan Palmer (1818-1902), a leading Presbyterian pastor and theologian, delivered his most famous defense of slavery and call for Southern secession in a Thanksgiving sermon preached to his New Orleans congregation, First Presbyterian Church, in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election to the U.S. presidency in November 1860. A year later, the first General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America elected Palmer as moderator.

“. . . the duty is plain of conserving and transmitting the system of slavery, with the freest scope for its natural development and extension. Let us, my brethren, look our duty in the face. . . . My own conviction is, that we should at once lift ourselves, intelligently, to the highest moral ground and proclaim to all the world that we hold this trust from God, and in its occupancy we are prepared to stand or fall as God may appoint."

(Benjamin M. Palmer, The South: Her Peril, and Her Duty. A Discourse, Delivered in the First Presbyterian Church, New Orleans, on Thursday, November 29, 1860. New Orleans: Office of the True Witness and Sentinel, 1860, pg. 7.)

For more information about Rev. Palmer, click here.

Rebel prayer

This pamphlet was published and distributed throughout the Confederacy, although it is not clear who the author is, or where it was published. The self described “Rebel Prayer” focuses on the theological virtues of the rebellion.

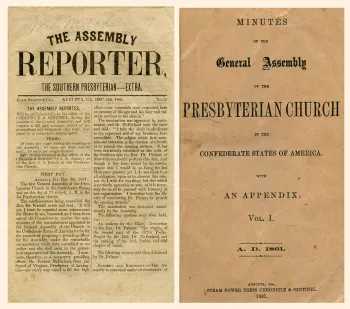

Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America Page 3

A month after the attack on Fort Sumter, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (Old School) convened in Philadelphia. A number of Southern commissioners did attend, inspiring some hope that the denomination would stay united by avoiding “politics.” However, Dr. Gardiner Spring of New York pushed through a resolution of support for the Union cause, and the Southern commissioners withdrew from the Assembly.

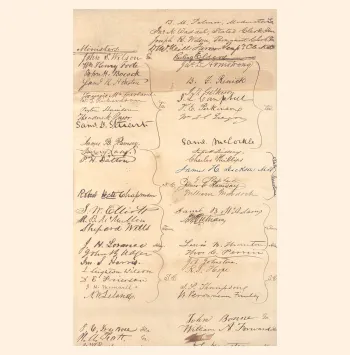

Delegates from eleven (of forty five) presbyteries in the Confederacy met in Atlanta in August 1861 to urge the formation of a new denomination called the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America (PCCSA). The convention Proceedings included a section “On the War.”

Benjamin Morgan Palmer (1818-1902), pastor of First Presbyterian Church in New Orleans, gave the opening sermon at the first PCCSA General Assembly. As in his famous Thanksgiving sermon of November 1860 that defended slavery and endorsed secession, Palmer relied on theology and rhetorical flourish to embolden the commissioners:

“…Let us take this young nation now struggling into birth, to the Altar of God, and seal its loyalty to Christ, in the faith of that benediction which says ‘blessed is that nation whose God is the Lord.’…May the rushing mighty wind of the Pentecostal day fill this house where we are sitting! and may the tongue of fire rest upon each of this Assembly!...”

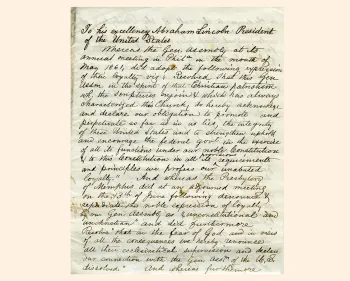

When war broke out in 1861, the Memphis Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (Old School), along with many other southern congregations and middle governing bodies, left the national denomination in order to form the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America. In this letter addressed to President Abraham Lincoln, the presbytery explains its reasons for secession.

Caring for Soldiers and Freedmen: USCC & Ladies’ Aid Societies Page 4

United States Christian Commission (USCC)

Throughout the war Presbyterian men and women worked to provide physical, emotional, and educational support to soldiers and freedmen. Both at home and on the front lines, they collected and distributed supplies, provided medical assistance, and offered spiritual guidance, education, and religious tracts. They joined in the efforts of their presbyteries and congregations, various agencies, including the United States Christian Commission (USCC) and the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), and organized their own soldier’s and ladies’ aid societies.

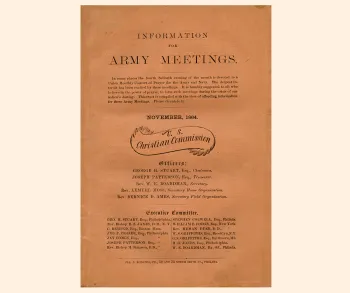

The U.S. Christian Commission, organized during a meeting of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in 1861, was created “to promote the spiritual and temporal welfare” of soldiers and sailors of the Union and Confederacy. Its activities included the publication of hymns and prayers, organizing devotional meetings in camps, and aiding and supporting chaplains.

Edward Parmlee Smith (1827-1876), Congregational minister in Massachusetts, served as field secretary of the USSC.

Prolific author and pastor of Presbyterian churches in Pennsylvania and Illinois, Rev. James Russell Miller (1840-1912) served the USCC as a field agent in the Army of the Potomac and Army of the Cumberland.

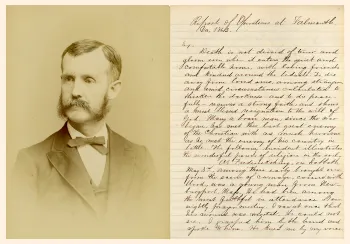

George H. Stuart (1816-1890), Philadelphia businessman and elder at the First Reformed Presbyterian Church, was chairman of the USCC and headed the executive committee of the Philadelphia Branch.

Ladies’ aid societies

Ladies’ aid societies and soldiers’ aid societies were often organized by women as part of their congregations’ larger efforts to support the troops. Some women participated through local hospitals and community organizations, while others chose to organize independently. In general, younger women who aligned themselves with the Union cause were more willing to travel long distances to assist soldiers directly on the front lines and in hospitals.

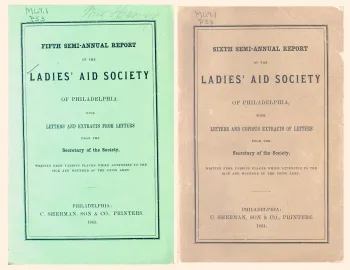

Working independently of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) and without denominational affiliation, the Ladies’ Aid Society of Philadelphia (LASP) dedicated itself to providing supplies, medical aid, and emotional and religious support to soldiers. Nicknamed the “Presbyterian Ladies’ Aid Society” because it held meetings and packed supplies in the basement of Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, it became one of the most famous and successful women’s charitable groups during the war. Ellen Orbison Harris, secretary of LASP, also worked in conjunction with the USCC as a field correspondent, travelling to hundreds of hospitals to care for Union and Confederate soldiers.

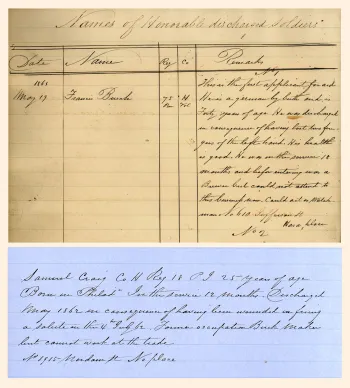

The Ladies’ Aid Society of Philadelphia kept a record of honorably discharged soldiers from 1863 through 1864, listing information such as soldiers’ names, addresses, reason for discharge, and any possible sources of assistance.

Caring for Soldiers and Freedmen: Chaplains Page 5

“I therefore offer myself as a volunteer to the service of my country and my God, in the capacity of Chaplain to the troops under your command.”

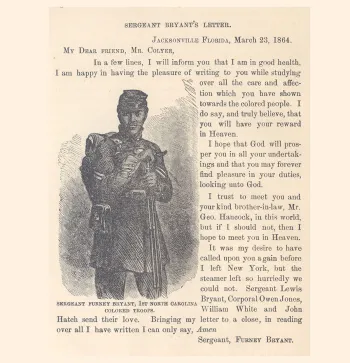

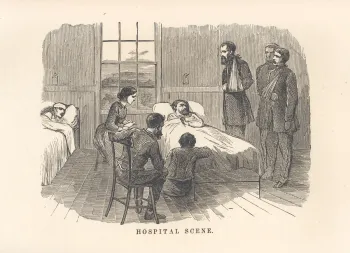

So wrote Alexander M. Stewart (1814-1875), pastor of the Second Reformed Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, in 1861, exemplifying the reaction of many Presbyterian clergy to the crisis of the Civil War. Chaplains to both Union and Confederate soldiers provided spiritual support and comfort by serving within various divisions of the military as well as in field hospitals. They held prayer meetings, religious services, Bible classes, and performed last rites. On the front lines, chaplains provided spiritual and emotional counseling and aid for the wounded, and in field hospitals they often assisted wounded soldiers with letter-writing to family and friends in addition to their religious duties.

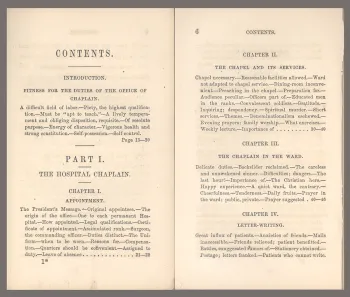

With no official policies governing the duties and responsibilities of chaplains, Union chaplains deferred to William Young Brown’s The Army Chaplain, while Confederate chaplains relied on James O. Andrew’s Letter to the Chaplains in the Army as a guide.

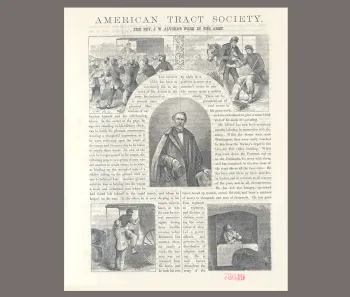

John W. Alvord (1807-1880) attended Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati and was ordained by the Congregational Church in 1836. In addition to serving as a chaplain to the Union Army during the Civil War, he held the office of secretary of the American Tract Society from 1854 to 1866. The American Tract Society, founded to promote Christian beliefs and values through the publication and distribution of religious tracts, featured the work of Rev. Alvord in this 1863 broadsheet to educate the public about the important role of the chaplain in the war effort.

In 1861, Texas evangelist Rev. Robert F. Bunting (1828 -1891) served as a commissioner to the organizing General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America. That same year, he entered military service as chaplain to the celebrated “Terry’s Texas Rangers” – the Eighth Texas Cavalry. For four years, he cared for the spiritual and bodily needs of his men while also serving as a war correspondent for several Texas newspapers and running a hospital for Confederate soldiers in Alabama. Serving congregations in Texas, Georgia, and Tennessee, his ministry spanned nearly forty years.

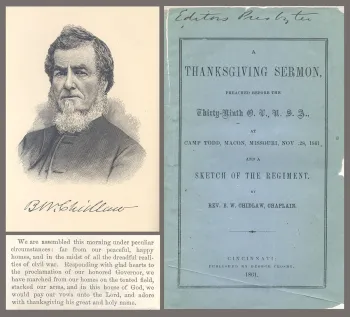

Rev. Benjamin W. Chidlaw (1811-1892) was a prominent Presbyterian Sunday School worker who became a Union chaplain for the Thirty-ninth Ohio Infantry at Camp Dennison in 1861. He spent less than a year as chaplain due to ill health, but he wrote fondly of his experiences in his autobiography, The Story of My Life. One of Chidlaw’s most remarkable memories as chaplain was his Thanksgiving sermon, delivered at Camp Todd Macon, Missouri, on November 28, 1861, about which he wrote:

“…This solemn occasion, standing in such a presence, our national life imperilled [sic], our country in the throes of a gigantic rebellion, and the horrors of war staring us in the face, made the delivery of my discourse the most trying and important effort in my life and experience…”

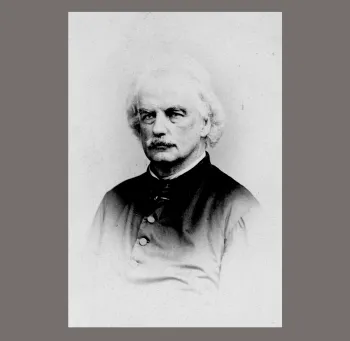

An outspoken and active supporter of Southern rights and institutions, Dr. Robert Lewis Dabney (1820-1898), professor at Union Theological Seminary, Richmond, Virginia, began his involvement in the war in 1861 as a Confederate chaplain to the Eighteenth Virginia Volunteers. Called an “Ironside Presbyterian parson,” his abilities as a chaplain drew the attention of General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, who recruited him in April 1862 to serve as his Chief-of-Staff, a combatant position he held for six months before suffering exhaustion. Dabney penned the first published biography of General Jackson at the request of Jackson’s widow.

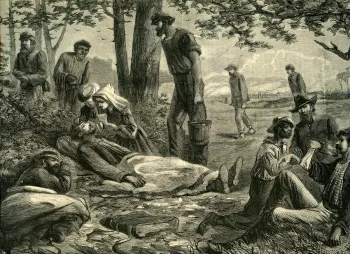

“…The signal of divine worship is the rattle of the drum, the soldier’s substitute for the bell, and they come from every side to the meeting-place,…rough-bearded men, bronzed and weather-beaten… Then follows the sermon, short and informal, but swallowed with solemn and eager faces. It is evident that many hearts are busy with thoughts of home… Not a few tears are wiped from those bronzed and bearded faces; but they are not unmanly tears; our enemies will find…that the love for homes and households…will make every one of these men as a lion in the day of battle…”

(Robert Lewis Dabney to the Central Presbyterian, 13 June 1861, in Thomas Cary Johnson, The Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney. Richmond, Va.: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, [1903], 236-237.)

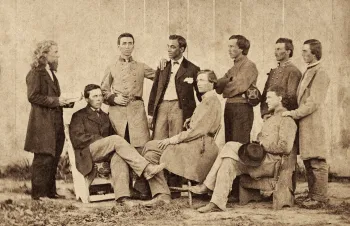

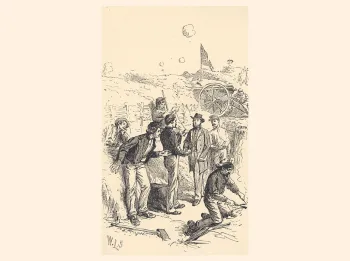

Rev. Isaac W. Handy (1815-1878) served congregations in Delaware, Missouri, Maryland, and Virginia. During the Civil War, the Union Army detained him at Fort Delaware for fifteen months for refusing to deny allegations that he made statements against the American flag. While at Fort Delaware, he preached every day and conducted Bible classes, contributing to the conversion of over seventy Confederate officers. The photograph here shows Rev. Handy (to the far left) preaching to fellow prisoners around 1863.

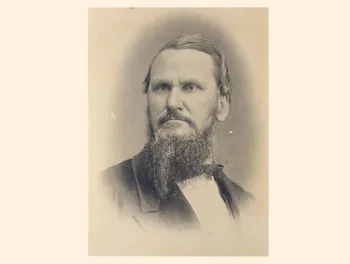

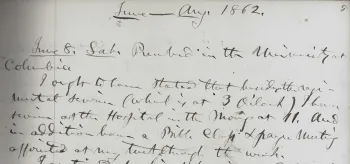

Born in Philadelphia to Baptist parents, Robert W. Landis (1809-1883) joined the Presbyterian Church at age twenty and was ordained in 1832. During the Civil War, Rev. Landis served three and a half years in the Union Army as a chaplain to a cavalry regiment. He kept a diary and recorded on the Sabbath, June 8, 1862:

“…I ought to have stated that besides the regimental service which is at 3 o’clock, I have services at the Hospital in the morning at 11. And in addition I have a Bible Class and prayer meeting appointed at my tent through the week…”

From 1868 to 1869, he occupied Dr. Robert J. Breckinridge’s chair at the Presbyterian Theological Seminary at Danville, Kentucky, and later served as a professor at the seminary.

Caring for Soldiers and Freedmen: Tracts & Outreach Page 6

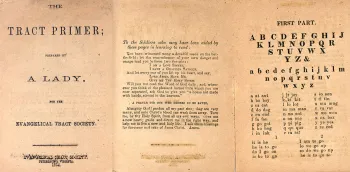

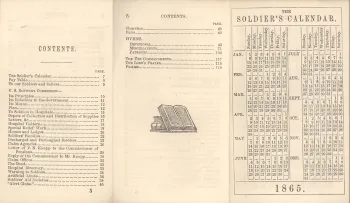

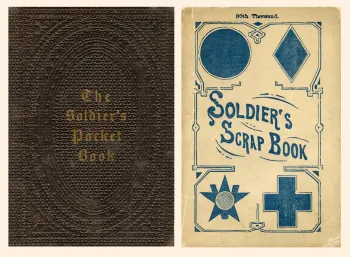

Tracts for soldiers

Throughout the war various agencies, including the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), the United States Christian Commission (USCC), the Presbyterian Board of Publication, the American Tract Society, and the Evangelical Tract Society, published booklets that were distributed to soldiers by chaplains, volunteers, and nurses serving in the field and in hospitals. These pocket-sized tracts were intentionally small so that soldiers could carry them in battle.

Outreach to freedmen

Northern Presbyterians at the national level formally organized Freedmen’s work during the war—in 1863 for the United Presbyterian Church of North America, and in 1864 for the Old School and New School branches of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Synods and presbyteries often led the effort, sending delegations south to set up and staff schools and provide other assistance.

After Union troops liberated the Sea Islands off South Carolina in 1862, Charlotte Forten (1837-1914) went to Fort Royal to teach the “contraband.” Charlotte was the first black teacher to journey south; she later married Presbyterian pastor Francis Grimké.

Presbyterian pastor and abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet (1815-1882) recruited freed slaves to fight for the Union and offered his support by collecting and distributing supplies and ministering to soldiers.

Individual Stories Page 7

Newspaper publisher, teacher, minister, President of the United States of America. These are just a few of the occupations held by Presbyterians during the Civil War. Their experiences and stories, some more well-known than others, are shared here.

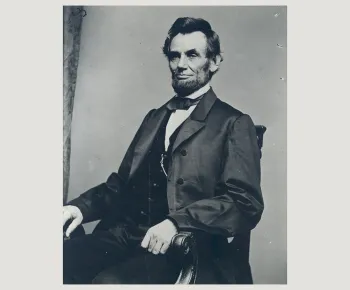

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)

Much has been written about Abraham Lincoln’s religiosity. His Christian attitude drew admiration from prominent figures in many religious traditions. Though his beliefs were generally nonsectarian, and he was never formally attached to any church, the Lincoln family attended the First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, Illinois, where Lincoln served as a trustee beginning in 1853.

Many sermons and orations marked the occasion of President Lincoln’s death on April 14, 1865. Among the most famous is the sermon delivered at the funeral, held at the Executive Mansion in Washington, D.C. on the nineteenth of April. Rev. Phineas Gurley (1816-1868) had been the Lincoln family’s pastor for four years at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington. The sermon reveals how Lincoln’s pastor viewed the president’s place in history. "Where reason fails, with all her powers, There faith prevails, and love adores," Gurley states in his oration.

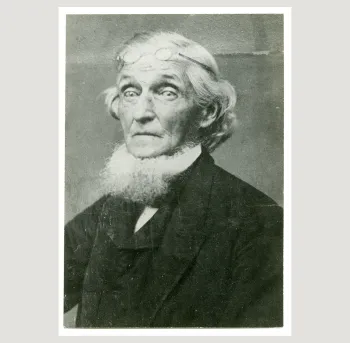

Amasa Converse (1795-1872)

Amasa Converse founded the Christian Observer in 1840. After the Civil War, it became the flagship newspaper of the Presbyterian Church in the United States. In his unfinished autobiography, Converse recorded his view on the volatile debates over slavery, which had split the Presbyterian church before the war:

“…In 1854 and afterwards while…the Christian Observer was pursuing the even tenor of its way, and gaining many new patrons, the abolition party was not at rest. The Church had repeatedly recorded its judgment on the subject of slavery: but nothing which the Church could say in its General Assembly seemed to quiet the agitators, the demand was reiterated by that party and continued from year to year for more action. At length in the New School Assembly of 1857, the blow was struck which severed the commissioners of the Southern from all connection with the Church in the Northern New School Assembly…”

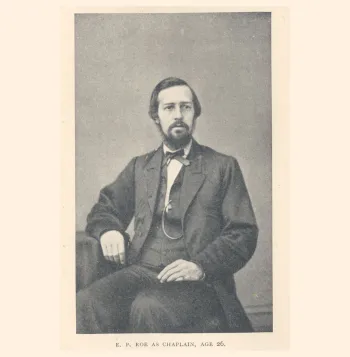

Rev. Edward Payson Roe (1838-1888) and Anna Sands Roe

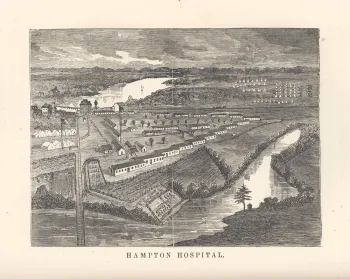

Fortress Monroe, Virginia remained under Union control throughout the Civil War and housed two military hospitals, Hampton and Chesapeake. Rev. Edward Payson Roe (1838-1888) served as chaplain of Hampton Hospital alongside his wife, Anna Sands Roe. Together they gave spiritual counseling, provided supplies, read and talked to wounded soldiers, and even campaigned for the installation of a hospital library.

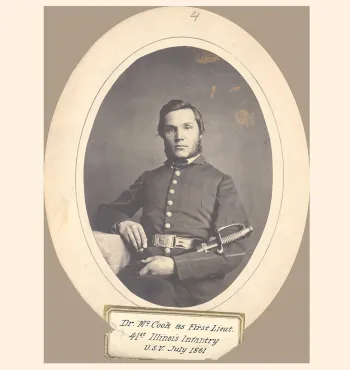

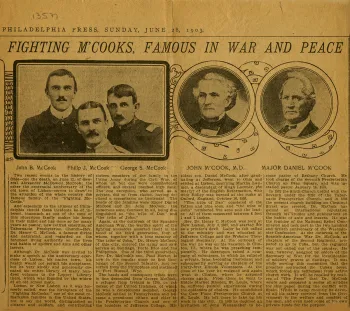

Henry Christopher McCook (1837-1911)

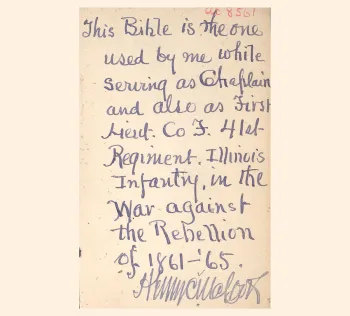

Born in New Lisbon, Ohio, on July 3, 1837, to a Scotch-Irish family known popularly as the “Fighting McCooks,” Henry C. McCook was one of fifteen McCook men to fight for the Union. Following the outbreak of the Civil War, McCook left the Western Theological Seminary in Pittsburgh and headed west that summer. He stopped in Clinton, Illinois, and enlisted as first lieutenant in the 41st Illinois Infantry. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed chaplain of the regiment. After nine months of military service, McCook resigned from the chaplaincy to serve as a volunteer aid on the staff of General John McArthur. Though he intended to take another position in the army, he was convinced by friends that he could serve his country best behind the pulpit.

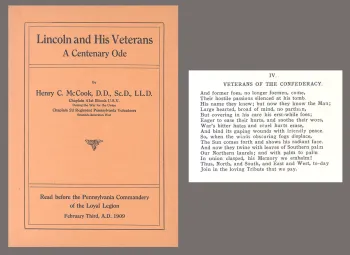

Years after his military service, McCook wrote an ode to commemorate the centenary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. He read his ode before the Pennsylvania Commandery of the Loyal Legion on February 3, 1909.

Moses Porter Snell (1839-1909)

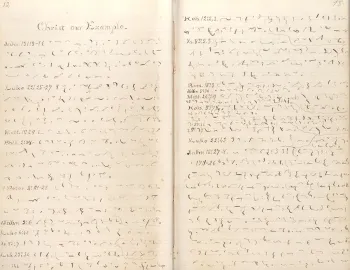

Moses Porter Snell acted as camp assistant to Union General Samuel Crawford during the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign in Virginia. While in camp during October of 1864, Snell kept this journal of biblical studies, written predominantly in short hand. A deeply religious man, Snell was later ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1887.

Margaret Elizabeth Breckinridge (1832-1864)

Presbyterian Sunday school teacher and nurse for the Union army, Margaret Breckinridge was born in Philadelphia on March 24, 1832 to an influential Presbyterian family. Her father was Presbyterian minister Rev. John Breckinridge, and her mother, Sunday school teacher Margaret M. Breckinridge, was the daughter of Princeton Theological Seminary professor, Rev. Samuel Miller.

Before beginning work as a volunteer hospital nurse, Margaret worked at home packing supplies for soldiers and writing letters and articles, such as “A Word about the War” for the Princeton Standard, in an effort to bring to light the pressing needs of soldiers and call upon what she saw as the duty of women in war time.

“…Talk as you may of the horrors of this civil conflict that is about to burst upon us, yet when you think of the holy cause for which we fight, when you remember how a nation of loyal hearts, roused from their trusting security, greeted that cause with a whirlwind of loving recognition that shook the land, when you consider who those are that go forth to fight for it, is there not a fitness, a grandeur in it, such as war has never yet known?...” (Memorial of Margaret E. Breckinridge, p. 39.)

Against the wishes of family and friends, she entered hospital service in 1862. Soon after beginning work in Baltimore, Margaret travelled to Lexington, arriving just before the invasion of Gen. Kirby Smith’s army. A few weeks after the Confederate army lost possession of the town, Margaret ventured on to St. Louis, where she worked in the hospitals of Jefferson Barracks. After spending two days in the Barracks, she wrote:

"…I shall never be satisfied till I get right into a hospital, to live till the war is over. If you are constantly with the men, you have hundreds of opportunities and moments of influence in which you can gain their attention and their hearts, and do more good than in any missionary field…” (Memorial of Margaret E. Breckinridge, p. 50.)

From St. Louis she completed two trips on hospital barges, transporting sick and wounded soldiers up and down the Mississippi River, before falling ill several weeks later. Struggling for a year through sickness and exhaustion, Margaret always intended to return to her post on the hospital boats. However, upon hearing that her brother-in-law, Col. Peter A. Porter, had been killed in battle, she rushed to comfort her family, embarking on a trip which proved too strenuous. She died shortly after arriving in Niagara Falls on July 27, 1864.

Samuel Fisher Tenney (1840-1926)

Samuel Fisher Tenney served in the Confederate army in Virginia and North Carolina. A devout Presbyterian, Tenney was ordained as a minister after the war. His son, Samuel Mills Tenney (1871-1939), founded the Historical Foundation of the Presbyterian and Reformed churches, which served as the archives of the southern stream of the Presbyterian Church in the United States.

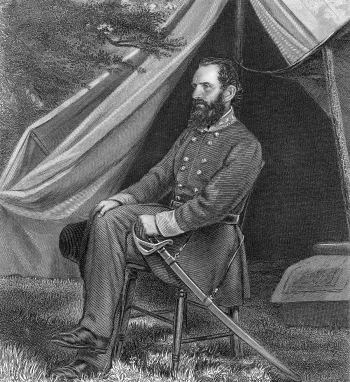

“Stonewall” Jackson (1824-1863)

As a boy, Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson was known for his gravity and sobriety of manner, and as an adult, for his tenacity and strategic genius. What is less well known is that he was a devout Presbyterian. While living in Lexington, Kentucky in the 1850s, he was seen every Sunday at the First Presbyterian Church. In 1857, he married Mary Morrison, the daughter of a prominent Presbyterian minister, and they had one child.