Presbyterians and the American Revolution

Presbyterians and the American Revolution Page 1

Exhibit Overview

Before the Revolution: As “Dissenters” from the established Church of England, Presbyterians mistrusted British colonial power—and were not afraid to assert a right to religious freedom when it was threatened. Presbyterian influence in the colonies grew markedly in the middle decades of the 1700s, shaped by the Great Awakening and an influx of Scottish and Scots Irish immigrants, most of whom were Presbyterian. With words and actions—and sometimes with violence—these religious dissenters challenged colonial rule, and many felt moved to defy the status quo in the name of God.

During the Revolution: Presbyterian response to the war was far from monolithic—there were Patriot, Loyalist, and neutral Presbyterians. But the majority of Church leaders supported the rebels. Twelve of fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence were Presbyterian, including the only clergyman, John Witherspoon. George Duffield of Philadelphia’s Third Presbyterian Church (today’s Old Pine Church, next door to the Presbyterian Historical Society) served as chaplain to the Continental Congress, and patriot pastors supported the war effort from their pulpits in every state. Everyday Presbyterians felt the war’s impact in their communities and houses of worship. British troops occupied Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Savannah. From New England to the Carolinas Presbyterian churches were seized to quarter troops or damaged by forces loyal to the Crown who saw the revolution as primarily a “Presbyterian Rebellion.”

After the Revolution: America’s victory in the war benefited the many Presbyterians who supported the Patriot cause. John Witherspoon remained in the nation he helped create, leading efforts to formalize the Articles of Confederation and the U.S. Constitution. Antislavery views gained proponents, and in 1787 the Presbyterian Church came close to calling for immediate abolition. African American Presbyterians began organizing their own congregations with First African Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia the first in 1807. Women built on their public involvement in the Patriot cause, forming missionary societies and establishing schools. By the time of the Second Great Awakening in the 1830s, women were the majority of members in most Presbyterian congregations—although still barred from ordained ministry. Americans had guaranteed their religious freedom but this victory did not shield them from the social and political tensions that played out as the new country struggled over the meaning of freedom and equality for all.

Click below to explore each exhibit page

Before: Asserting a Right to Religious Freedom Page 2

Presbyterians took stands for religious and civil liberty well before the American Revolution. As “Dissenters” from the established Church of England, they mistrusted British colonial power—and were not afraid to assert a right to religious freedom when it was threatened.

Francis Makemie (1658-1708) arrived in the American colonies from Northern Ireland in the 1680s and founded a number of Presbyterian churches. In 1707 Lord Cornbury, the governor of New York, ordered him arrested for preaching without a license as required by the British government. Makemie spent two months in jail before his release on bail. At trial he produced his preaching license and was acquitted but not before incurring heavy legal costs. This became a landmark case in favor of religious freedom in America.

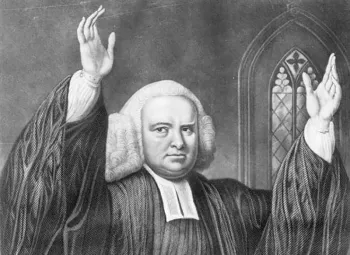

The mid-eighteenth-century Great Awakening fostered in many people a deeply personal Christianity that led them to act in ways that challenged established religious authorities, often stretching cultural norms of gender and race. Revivalist preacher George Whitefield (1714-1770), an English Anglican, fired the Great Awakening in America with his preaching from Georgia to New England.

Samuel Davies (1723-1761) ministered to Native Americans and enslaved African Americans in Virginia and influenced a young Patrick Henry.

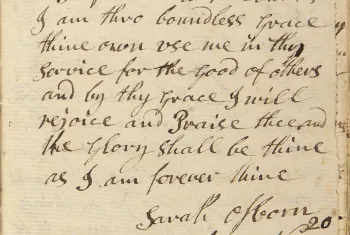

Sarah Haggar Wheaton Osborn (1714-1796) was a teacher and Congregational leader in Newport, Rhode Island. In the early 1740s, revivalist preachers George Whitefield and Presbyterian Gilbert Tennent deeply inspired Osborn, and she began to host Bible discussions with women from her neighborhood. By the 1760s, her weekly meetings attracted hundreds of people, including slaves—much to the dismay of some Newport residents who believed women should not act as religious leaders at all, much less to crowds of mixed race and gender.

Presbyterian influence in the colonies grew markedly in the middle decades of the 1700s, shaped by the Great Awakening and an influx of Scottish and Scots Irish immigrants, most of whom were Presbyterian. The heady mix of evangelical religion and increased population propelled Presbyterians to establish local academies and colleges to educate leaders for the growing flock.

William Tennent (1673-1746) founded the first school to educate Presbyterian ministers in colonial America in 1727. During the Great Awakening his "Log College" and its graduates adhered to the evangelical views espoused by George Whitefield, Samuel Davies, and other "New Side" Presbyterians.

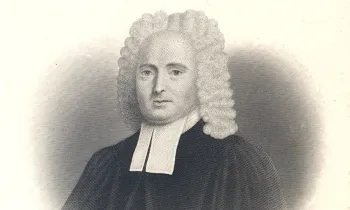

Francis Alison (1705-1779) was one of the most influential Presbyterian pastors and educators in the decades leading up to the Revolutionary War. Alison was born in Ireland, educated at the University of Glasgow, and arrived in the colonies in the 1730s. He stood with “Old Side” Presbyterians during the Great Awakening, and founded the New London Academy in Pennsylvania. He later taught at the College of Philadelphia and Newark Academy in Delaware. Three signers of the Declaration of Independence studied under Alison as did Presbyterian Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress.

Before: Religious and Political Conflict in the 1760s Page 3

In Pennsylvania, many of the new Presbyterian immigrants settled in frontier areas. Conflicts with Native Americans and concerns about Quaker political dominance erupted in violence in late 1763 when the Paxton Boys massacred a group of peaceful Susquehannock Indians near Lancaster. A larger group then marched on Philadelphia in early 1764. Benjamin Franklin rallied a militia that stopped the Paxton Boys outside the city, but the incident sparked much political tumult, especially between Quakers and Presbyterians who were labeled “Piss-brute-tarians (a bigoted, cruel and revengeful sect).” To counter the Presbyterians, Franklin backed a plan to install a royal government in Pennsylvania in place of the Penn proprietorship. Leading Presbyterian ministers including Gilbert Tennent and Francis Alison spoke out against a royal charter, and the conflict prompted formation of the first committees of correspondence—organized by Pennsylvania Presbyterians to oppose Franklin and his scheme. The Presbyterians and their allies succeeded, and a decade later committees of correspondence became a hallmark of American opposition to British rule during the Revolution.

Political cartoons of the era captured the animosity between Quakers and Presbyterians. In the drawing below, Quaker merchant Israel Pemberton, identified by his initials “IP” on the barrel in the lower left, gives hatchets to the Indians, telling them to “Exercise those on the Scotch Irish & Dutch & I’ll support you while I can.” Benjamin Franklin, in the right foreground, stands holding a bag of Pennsylvania money saying he will be content if he gets the government. A group of Quaker men sit behind them at the table and fret over the colony’s fate with one of them saying, “I’m afraid those wicked Presbyterians will get their ends accomplished.”

Presbyterians joined others in criticizing the Anglican Church, contributing to the revolutionary fervor by undermining the concepts of authority that had denominated colonial life. Controversy over the possible appointment of an Anglican bishop for the colonies heated up in the 1760s with George III's accession to the British throne.

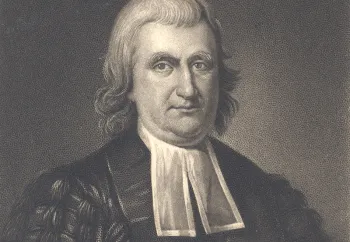

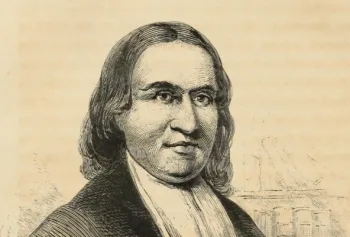

Into this charged atmosphere came John Witherspoon. He arrived from Scotland in 1768 to lead the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), the school founded by “New Side” Presbyterians in 1746. Although seen as a moderating force initially, Witherspoon was quite outspoken in his support for the patriot cause. Both Witherspoon and Francis Alison strongly opposed the installation of an Anglican bishop in America. Witherspoon served in the Continental Congress and was the only active minister to sign the Declaration of Independence. He also educated a number of leading revolutionaries including James Madison and Aaron Burr.

During: Urging Americans to Arms Page 4

The Presbyterian response to the Revolutionary War was far from monolithic—there were Patriot, Loyalist, and neutral Presbyterians. But the majority of church leaders supported the rebels. Twelve of fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence were Presbyterian, including the only clergyman, John Witherspoon. Others supported the war effort as chaplains and soldiers, and from their pulpits and pews.

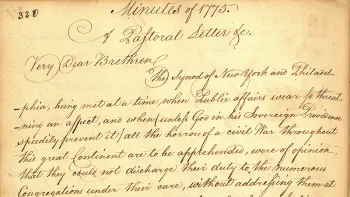

In the spring of 1775, the Synod of New York and Philadelphia, the national governing body of American Presbyterians, circulated a pastoral letter among its members to prepare them for the war ahead:

“If…the British Ministry shall continue to inforce their claims by violence, a lasting and bloody contest must be expected.” Counseling fortitude, the letter reminded Presbyterians that, though “it may please God, for a season, to suffer his people to lie under unmerited oppression, yet…we may expect, that those who fear and serve him in sincerity and truth, will be favoured with his countenance and strength.”

Strongly influenced by Witherspoon and the Philadelphia ministers George Duffield and Francis Alison, “radical” ministers such as John Rodgers in New York, David Caldwell in North Carolina, and John Blair Smith in Virginia espoused the principles of individual and national liberty to their congregations. From the pulpit of New York City’s Wall Street Church, Rodgers (1727-1811), a staunch patriot who would later serve as a chaplain during the war, lauded those Continental army volunteers who chose “rather to risk their lives in the cause of liberty, than to resign their privilege and live in slavery.”

During: The Fighting Presbyterians Page 5

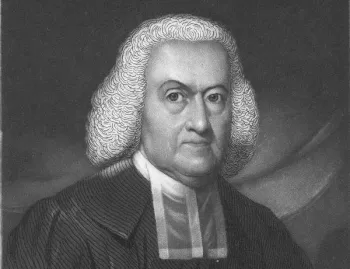

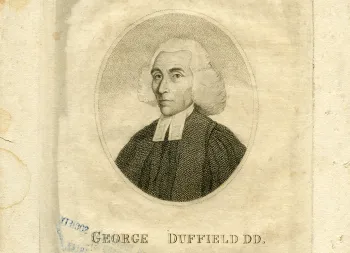

George Duffield (1732-1790) left his role as pastor at Third Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia to serve as Chaplain of the Pennsylvania Militia and co-Chaplain of the Continental Congress. Sixty men from his congregation joined him in the army; their collective service earned Third Presbyterian the nickname “Church of the Patriots.”

John Rosbrugh (1714-1777), an Irish immigrant and Presbyterian pastor in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, was the first chaplain killed during the war. In 1776, Rosbrugh and members of his congregation organized the third Northampton County, Pennsylvania militia, and Rev. Rosbrugh accepted a commision as their chaplain. The militiamen then joined General George Washington and the Continental Army. During the Second Battle of Trenton in January 1777, Rosbrugh was bayonetted and killed by Hessians.

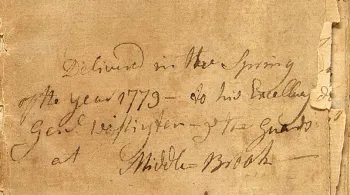

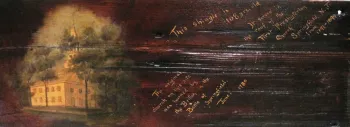

James Francis Armstrong (1750-1816) studied under John Witherspoon at the College of New Jersey in the years before the war. He was ordained in 1776, and soon began a career as a chaplain that lasted until 1782. In 1779, he preached a sermon to George Washington’s troops at the Middlebrook encampment near Bridgewater, New Jersey. The manuscript copy of the sermon still exists in the collection of the First Presbyterian Church in Trenton, New Jersey.

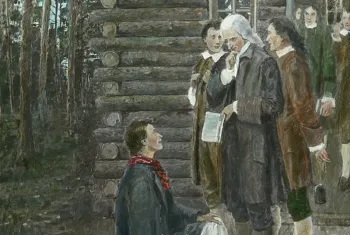

Other Presbyterian chaplains and officers gave their lives to the Patriot effort. James Caldwell (1734-1781), pastor of the Presbyterian Church in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, earned the moniker the “fighting parson” for his commitment to the rebel cause. Like Duffield and Armstrong, he served as a chaplain, in this case to the Continental Army. During the June 1780 Battle of Springfield, Caldwell exhorted American troops to use pages from copies of Isaac Watts’ Hymnal as gun wadding. Legend has it that Caldwell told the troops, “Give ‘em Watts, boys!” or “Put Watts in them, boys!”—a scene vividly rendered in Henry Alexander Ogden’s watercolor, “James Caldwell at the Battle of Springfield.”

After the Battle of Springfield, British forces burned down the First Presbyterian Church of Springfield, New Jersey, and the surrounding village. Later that month, Caldwell’s wife Hannah was shot and killed after the Battle of Connecticut Farms in Union Township, New Jersey. Reverend Caldwell died in November 1781, also on the fringes of battle, when an American sentry shot him—reportedly for refusing to allow the search of a package he was carrying.

Another Presbyterian martyr was Hugh Mercer, a Scottish-born physician who became an officer in the Continental Army in 1776. Instrumental in General Washington’s victories in Trenton in December 1776, Mercer was leading a group of Washington’s soldiers to Princeton in early January 1777 when his brigade encountered British troops. Mercer was mistaken for George Washington and ordered to surrender; though he fought for his life, he was killed by British soldiers.

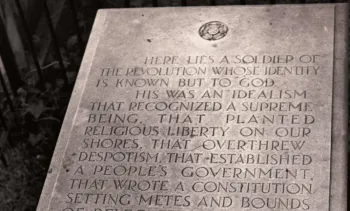

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Old Presbyterian Meeting House in Alexandria, Virginia, serves as a poignant memorial to the war’s many dead. The permanent tombstone dates to 1929, when Alexandria's American Legion Post 24 led a nationwide effort to erect the permanent tribute.

During: War Stories Page 6

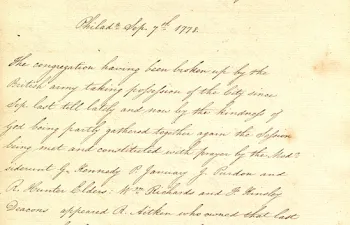

Ordinary Presbyterians were drawn into the war on either side of the conflict--or sometimes on both. The session minutes of Scots Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a predecessor of today’s Old Pine Presbyterian Church, recount an episode involving "R. Aitken," who signed an oath of allegiance to the “king of Britain” after previously siding with the forces of the Continental Congress.

Presbyterian Elias Boudinot (1740-1821) was Commissary General of Prisoners from 1777 to 1782, when he was elected President of the Continental Congress. Throughout the war Boudinot oversaw the housing and provisioning of prisoners and ruled on petitions for clemency and early release.

Among Boudinot’s papers at the Presbyterian Historical Society is a 1778 letter from a prisoner named “A. Skinner,” who managed to find grace in the idea that should he die in prison, he would “Die … like an American, and with the full Satisfaction of having Done my Country that Service it was Entitled to, from me, and in hopes of Meeting a Proper Reward in the next World.”

Everyday Presbyterians also felt the war’s impact in their houses of worship. British troops occupied Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Savannah. From New England to the Carolinas Presbyterian churches were seized to quarter troops or damaged by forces loyal to the Crown who saw the revolution as primarily a “Presbyterian Rebellion.”

Originally from Pennsylvania, Presbyterian physician David Ramsay (1749-1815) had settled in Charleston, South Carolina, before the war’s outbreak. In 1780 he was arrested in that occupied city by British forces and sent to prison in Florida. After the war he served in the Continental Congress. His experiences during the war prompted him to write one of the first published histories of the Revolutionary War, History of the Revolution in South Carolina (1785).

During: Difference and Dissent Page 7

Not all Presbyterians were Patriots, nor were all Patriots men. Presbyterian women who backed the rebel cause boycotted the importation and use of British goods. Their efforts were satirized by British cartoonist Philip Dawe in his depiction of a group of North Carolina women drafting a petition to boycott English tea in response to the Continental Congress’s resolution to boycott British goods.

African Americans and Native Americans fought on both sides of the war, seeking to preserve native lands or gain individual freedom. On the western frontier, where tensions between Patriot settlers and Native Americans were especially high, Presbyterian minister Samson Occom —a member of the Mohegan tribe of east-central Connecticut who converted to Christianity at age 18—encouraged other native Christians to remain neutral.

Loyalist ministers and lay leaders could be found at Presbyterian churches throughout the colonies—men such as John Zubly of Savannah’s Independent Presbyterian Church and William Smith, Jr. of New York City’s First Presbyterian Church. In Philadelphia, Quaker and Anglican Tories made common cause with Presbyterian Loyalists such as William Allen (1704-1780), one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest men.

In 1780, Anglican minister Jonathan Odell wrote, “I’d rather be a dog than Witherspoon.” Three years later, after the Treaty of Paris formally ended hostilities, Odell found himself a resident of British-controlled Canada. John Witherspoon remained in the nation he helped create, leading efforts to formalize the Articles of Confederation and the U.S. Constitution.

After: Presbyterians Following the War Page 8

America’s victory in the Revolutionary War benefited the many Presbyterians who supported the Patriot cause. John Witherspoon led the College of New Jersey, later to become Princeton University, until his death in 1794.

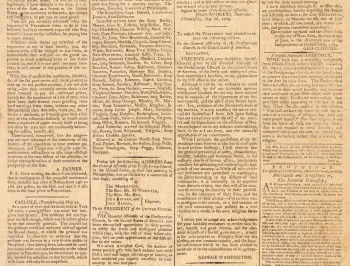

Presbyterians were instrumental in laying down the foundations of higher education in the new nation. Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, worked with Rev. Dr. John King of Franklin County, Pennsylvania, to help organize Dickinson College, which was chartered in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. It was the first college founded after the formation of the United States, six days after the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War in September 1783.

New Presbyterian schools such as Centre College in Kentucky and Davidson College in North Carolina helped to educate Americans as the nation grew.

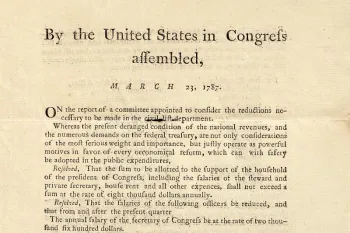

The new nation now had to govern and determine its own future. Presbyterian Charles Thomson (1729-1824), Secretary of the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1781 and Secretary of the Assembled Congress from 1781 to 1788, signed this act of Congress stipulating that salaries for persons charged with maintaining the household of the “president of Congress” not exceed $8,000 per year. It also called for reduced salaries for various leaders, including the Secretary of Congress and the Secretary of Foreign Affairs.

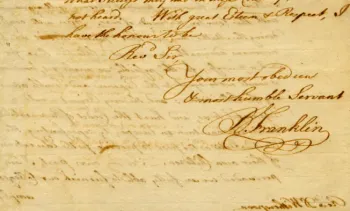

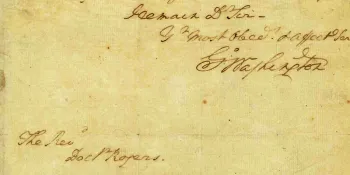

Meanwhile, in the peace following the Revolutionary War, Presbyterians were forming a national church. Presbyterians organized the first General Assembly in the United States in 1789 in Philadelphia. Writing on behalf of the first General Assembly, moderator John Rodgers wrote of the “unfeigned pleasure” the assembly felt at the appointment of George Washington to the “first office” in the nation.

In a 1784 letter to Rodgers, Washington had expressed how he read with “great pleasure” Rodgers' Thanksgiving Sermon, The Divine Goodness Displayed, in the American Revolution.

After: Freedom and Equality for All Page 9

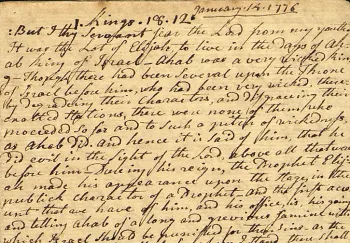

In the war’s aftermath, the fate of slavery remained an open question. On May 26, 1787, an overture came before the Synod of New York and Philadelphia, calling on all pastors, churches, and “families under their care, to do every thing in their power consistent with the rights of civil Society to promote the abolition of slavery, and the instruction of Negroes whether bond or free.”

Two days later, delegates approved a watered-down version of the overture, praising “the general principles in favor of universal Liberty that prevail in America,” but noting that newly-freed slaves might be “dangerous to the community” and endorsing a plan “to give those persons who are at present held in servitude such good education as to prepare them for the better enjoyment of freedom.” They further recommended “to all their people to use the most prudent measures…to procure eventually the final abolition of Slavery in America.”

The final abolition of slavery across the United States would not come for another seventy-eight years; African Americans in the South would continue to live in bondage even as some attended Presbyterian churches. Johns Island Presbyterian Church in South Carolina was founded in 1710. When it exlarged its sanctuary in 1823, the congregation added a balcony where slaves worshipped during services.

African American Presbyterians began organizing their own congregations in the early nineteenth century. First African Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia was the first, founded in 1807. It was organized by John Gloucester, a former slave from Tennessee who became a Presbyterian minister.

Women built on their public involvement in the Patriot cause. The church provided an acceptable outlet for women to be socially engaged. It was at the beginning of the nineteenth century that many churches formed women’s societies that provided relief to the poor, aided missionaries, and established schools. By the time of the Second Great Awakening in the 1830s, women were the majority of members in most Presbyterian congregations.

One of the most active women in the Presbyterian Church following the American Revolution was Isabella Marshall Graham (1742-1814). Graham was a Scottish teacher and philanthropist called to Christ under the ministry of John Witherspoon in Paisley, Scotland. She immigrated to New York in 1789 and founded several benevolent societies, including the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows.