Foundations of the Faith

Foundations of the Faith Page 1

In Western Europe, the authority of the Catholic Church remained largely unquestioned until the Renaissance in the fifteenth century. Around 1450, the invention of the printing press in Germany made it possible for the masses to read the Bible and other religious texts, enabling the discovery of religious thinkers who had begun to challenge the Church. The term “Reformation” is used to describe the series of changes in Western Christendom between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries. The early sixteenth century, in particular, brought divergences from Catholic doctrine caused by the perceived financial excesses of the Papacy and the Curia.

The emerging Reformed churches are those that were influenced by the theology of reformers such as Desiderius Erasmus, Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli, Philipp Melanchthon, John Calvin, Théodore de Bèze, and John Knox. Designation of these ‘Protestant’ churches as Églises réformées, reformierten Kirchen, and ecclesiase reformatae was common before the end of the sixteenth century.

This exhibit examines sixteenth century European reformers and their contributions to the Reformation. Unless noted, all images are sourced from the society's collections.

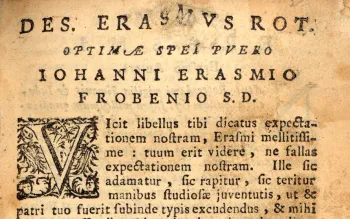

Desiderius Erasmus: Humanist of Rotterdam Page 2

As the “Father of the Reformation,” Desiderius Erasmus (1466/69-1536) and his writings influenced theologians, scholars, and common people. But ultimately, Erasmus was a humanist, not a theologian or a radical reformer, and he remained a member of the Catholic Church for his entire life. Decades after his death, the Council of Trent listed his writings on the Index of Prohibited Books.

For his time, Erasmus held rather unconventional teaching views. He encouraged physical education, criticized the use of harsh discipline, and insisted that students learned better when teachers stimulated their interest. As the foremost scholar and humanist of the period, his acquaintances included Thomas More, John Colet, and Henry VIII.

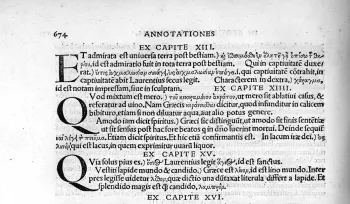

With the upheaval of religious thought during the Renaissance, new versions of scripture emerged. One of the first was Erasmus’ 1516 New Testament in Greek and Latin which he derived from several partial Greek manuscripts. This new edition comprised a vastly different interpretation from the Vulgate, the Latin version of the Bible accepted and used for centuries by the Catholic Church. In the preface to his New Testament, Erasmus urged others to continue his work by translating the Bible into their native languages. Many reformers, such as Martin Luther, did just that. In addition, scholars and theologians into the modern era used Erasmus’ text as the basis for other important biblical translations and commentaries. As Erasmus wrote, “it is an unscrupulous intellect that does not pay to antiquity its due reverence” (Works of Hilary, preface, January 5, 1523).

Martin Luther: Founder of the German Reformation Page 3

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was ordained as a priest in 1507 and became a professor of biblical interpretation at the University of Wittenberg in 1508. Under Luther’s influence, the Wittenberg faculty of theology was committed to a program of theological reform based on "the Bible and St. Augustine." Luther also contributed to major theological reform by translating the Bible into vernacular German, which enabled the masses to hear and read the gospel of Jesus Christ in their own language.

In 1517, Luther launched a movement against the Catholic Church when he posted his 95 Theses, or Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, on the door of the castle church at Wittenberg.

In 1520, Pope Leo X warned Luther with the papal bull, an official papal document written in response to Luther's 95 Theses, ordering him to recant 41 sentences from his Theses and subsequent writings or face excommunication. Luther responded by publicly burning the document and was excommunicated in 1521.

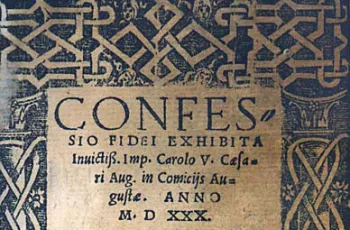

The Lutheran confession of faith, the Augsburg Confession (1530), was mainly the work of Philipp Melanchthon, who, after receiving the approval of Martin Luther, presented it at Augsburg to the Emperor Charles V. To make the Lutheran position as inoffensive as possible to the Catholics, the Confession’s language was studiously moderate. A considerably revised text issued by Melanchthon in 1540 was accepted by the Reformed (Calvinist) churches in Germany.

Ulrich Zwingli: Swiss Reformer Page 4

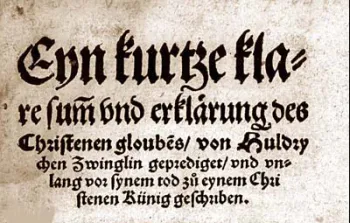

Ordained as a priest in 1506, Ulrich Zwingli (1484–1531) was a devoted admirer of Desiderius Erasmus. He used the Dutch humanist’s 1516 edition of the Greek New Testament to enrich his knowledge of the original text. Unlike Martin Luther, Zwingli experienced no acute religious crisis--he became a reformer through his studies. A dominant political as well as ecclesiastical force in Switzerland, Zwingli is considered to be one of the more liberal Reformers.

In 1518, Zwingli was elected preacher at the Minster in Zurich, Switzerland. The start of the Swiss Reformation is credited to Zwingli’s sermons on the New Testament, which he preached in 1519. In 1523, before the Council of Zurich, Zwingli presented and defended his doctrines in a public disputation. His theses included establishing the Bible as the sole basis of truth and rejecting the authority of the Pope, the Mass, saints, fasting, and clerical celibacy. Supported by the city council, Zwingli’s church reforms were rapidly put into effect. Zwingli developed his characteristic interpretation of the sacraments in a series of published sermons that contributed to the development of a Reformed theology. In 1524-25, Zwingli began to develop a purely symbolic interpretation of the Eucharist, producing a series of writings against Martin Luther’s doctrine of consubstantiation.

Philipp Melanchthon: German Reformer Page 5

In 1518, Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560) became a professor of classics and philosophy at the University of Wittenberg, where he was influenced by Martin Luther. Though he was born Philipp Schwartzerdt in Bretten, Germany, his uncle and teacher called him “Melanchthon”--the Greek version of his last name, translated as “black earth,” for his achievement in Latin and Greek. He authored numerous treatises, biblical commentaries, and translations, including a revision of Luther’s translation of the New Testament. While Luther was confined in the Wartburg in 1521, Melanchthon headed the Reformation in Germany.

During the controversy on Eucharistic doctrine, from 1525 to 1536, he was a solid supporter of Luther against the followers of Ulrich Zwingli. The chief architect of both the Augsburg Confession (1530) and Apology of the Augsburg Confession (1531), Melanchthon was often criticized for his conciliatory views towards Roman Catholicism. He was hailed as a major innovator in German education and seen by some as the primary organizer of the German public school system. His teachings on free will, known as synergism—cooperation between God and man—caused many to accuse him of being too humanistic. He faced strong objections from strict Lutherans due to his continued work to create areas of agreement with some Catholic views. He died in Wittenberg on April 19, 1560.

1888 edition of the Augsburg Confession. Translated into English by Richard Taverner. Edited by Henry E. Jacobs. From Internet Archive via Princeton Theological Seminary Library.John Calvin: French Theologian and Reformer Page 6

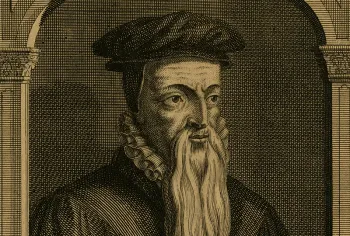

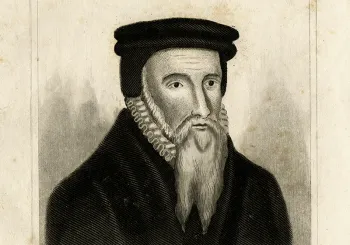

An intelligent member of the Catholic middle-class, John Calvin (1509-1564) had the family connections to place him in good schools. He left home in Noyon, France, in 1523, and traveled south to Paris to study law on a church scholarship. There he was exposed to theological conservatism, humanism, and a movement calling for the reformation of the church.

Young Calvin, his name Latinized to Ioannis Calvinus, completed his studies and settled in Paris. He experienced what he described as “a sudden conversion” and joined reform-minded activists who were taking stronger and more public stands on church reform. When his friend Nicholas Cop was installed as rector at the University of Paris in 1533, Cop advocated for church reforms in his inaugural address. Some believed Calvin authored Cop’s controversial remarks, which showed affinities with Desiderius Erasmus and Martin Luther, and Calvin was forced to flee Paris.

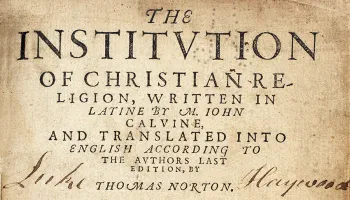

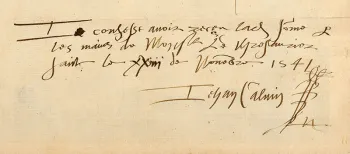

The twenty-four year old Calvin relocated to Reformation-minded Basel, where in 1536, he wrote his six-chapter distillation of evangelical faith, published in Latin: Christianae religionis instituto, or Institutes of the Christian Religion. This treatise was systematic and clear. It derived much of its form and substance from Luther’s Kleiner Katechismus (1529) and addressed law, the Decalogue, the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the sacraments, and Church government.

Passing through Geneva later that year, he was persuaded to stay and assist in organizing the Reformation in that city. However, on Easter Day 1538, Calvin publicly defied the city council’s instructions to conform to the Zwinglian religious practices of Berne and was ordered to leave. After serving as pastor to the French congregation in Strasbourg for three years, Calvin accepted an invitation to return to Geneva. In 1541, he began fourteen years of work to establish a theocratic regime in the city, and his Ecclesiastical Ordinances were adopted by the city council in November 1541. These ordinances distinguished four ministries within the church: pastors, doctors, elders, and deacons. Other reforming measures included introducing vernacular catechisms and liturgy.

Over time, John Calvin expanded on and refined his thinking in the Institutes. Responding to the considerable interest in the work and the controversy it generated, he issued a much expanded eighty-chapter version. The text became the most important theological text of the Reformation. The 1559 Latin edition was widely circulated in various forms, becoming the theological source document of Protestantism. The Institutes is hailed as the cornerstone of Calvinist theology.

1845 edition of Calvin's Institutes, translated into English by Henry Beveridge. From Internet Archive via Princeton Theological Seminary Library.Calvin’s theology proved to be the driving force of the Reformation, particularly in Western Germany, France, the Netherlands, England, and Scotland. It was from Calvin that John Knox gained the knowledge of Reformed theology and polity that he used as the basis for founding the Presbyterian denomination.

Théodore de Bèze: French Calvinist Theologian Page 7

In 1528, while studying law at the university in Orleans, France, theologian and scholar Théodore de Bèze (1519-1605) was greatly influenced by Melchior Wolmar, a German scholar who had also mentored John Calvin. Thirty years later, in 1558, Bèze accepted an offer from Calvin to teach at the newly founded academy at Geneva. In 1559, he published his Confession de la foi chretienne, an exposition of Calvinist beliefs, which was translated into Latin in 1560. Upon the death of Calvin in 1564, Bèze succeeded him as head of the Genevan Church and leader of the Calvinist movement in Europe.

Bèze’s New Testament went through five editions during his lifetime. The work was intended to replace Erasmus’ Greek text, Latin translation, and annotations, which Bèze considered doctrinally and textually unsound.

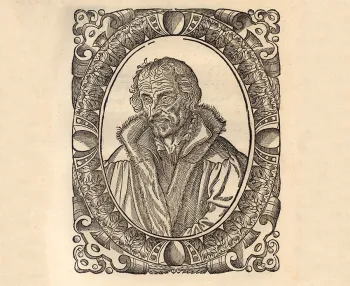

Bèze’s Icones (1580) contains portraits and biographies of religious leaders who contributed to the Reformation of the church. View C.G. Goulard's facsimile of the full volume below.

C.G. Goulard's Bèze's Icones: Contemporary Portraits of Reformers of Religion and Letters, facsimile reproductions of the portraits in Bèze's Icones (1580) and in Goulard's edition (1581). From Internet Archive via University of Toronto Libraries.John Knox: Scottish Reformer Page 8

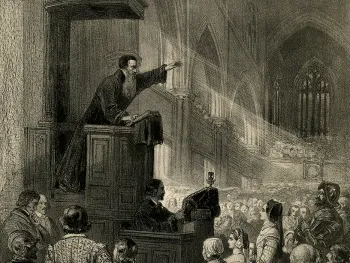

John Knox (ca. 1514-1572) was a leader of the Reforming party in his native Scotland. Knox studied with John Calvin in Geneva and took Calvin’s teachings back home with him to Scotland. The Presbyterian Church traces its ancestry back primarily to Knox in Scotland and to England, and so Knox is widely regarded as the founder of Presbyterianism.

Educated in Glasgow and possibly at St. Andrews, Knox received minor orders, set up as a notary in Haddington, and then became a private tutor, c. 1544. Soon afterwards he embraced the principles of the Reformation. After being taken prisoner by the French during their attack on St. Andrews, he made his way from France to England, where he served briefly as chaplain to Edward VI. Shortly after Queen Mary Tudor's ascension to the throne in 1553, he fled to Geneva, where he met and was influenced by John Calvin.

Eventually returning to Scotland in 1559, after more than a decade abroad, Knox became a minister in Edinburgh and, soon after, the acknowledged leader of the Reforming party in the Kirk.

In close collaboration with his ministerial colleagues, Knox published three influential documents in the course of the next few years that were to be his principle contribution to the Reformation in Scotland—and to the religious and social history of his nation for the next century. He contributed to the writing of the Scots Confession (1560), a short evangelical consensus of Reformed doctrine and the principal theological standard of the Kirk until it was superseded by the Westminster Confession in 1647. He was the main author of the Book of Common Order (1556-64), based on prayer forms used by Knox in Geneva and widely used in Scottish worship until the adoption of the Westminster Directory of Public Worship in 1645.

Knox's Book of Common Order, commonly called John Knox's Liturgy. Translated into Gaelic by John Carswell, 1567. Edited by Thomas McLauchlan, 1873. From Internet Archive via National Library of Scotland.Another of Knox’s most significant works is History of the Reformation of Religion within the Realms of Scotland. Originally issued in an unfinished edition in 1587, it was immediately seized and suppressed. The first complete edition appeared in 1644.

1644 edition of Knox's History of the Reformation of Religion within the Realms of Scotland. From Internet Archive via Princeton Theological Seminary Library.In the (first) Book of Discipline (1560), Knox and the Reformers worked out their concrete program of reform in both church and society. Knox’s goal was to create in Scotland nothing less than the “Godly Commonwealth” of ancient Israel. Had the education and charity provisions of the Book of Discipline been implemented as Knox wished, Scotland would have had the first program of systematic poor relief and universal compulsory primary education in Western Europe. Comprehensive, egalitarian, and practical—but hardly democratic—the Book is still recognized as a landmark of Christian social reform.

It was said after his death that Knox was a man who neither feared nor flattered anyone alive. Scotland would have had a Reformation without him, but it was from him that it received much of its distinctive character and direction. American Presbyterians, as heirs of the church he helped to create, owe something of their character to his moral courage and social vision.