Dr. Thelma Adair, the first African American woman elected Moderator of the General Assembly, dies at 103

She’s remembered as a passionate educator, church leader and human rights advocate

LOUISVILLE — Dr. Thelma Cornelia Davidson Adair, the first African American woman to be elected Moderator of the General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, died Aug. 21 at the age of 103. A private service was scheduled.

Adair is remembered as a passionate educator, church leader and human rights advocate. She was elected Moderator of the 188th General Assembly in 1976 in Baltimore. As the top ambassador for the church, she traveled to 70 countries and met with local, regional and national leaders, including former President Gerald Ford in 1977.

Some highlights of Adair’s accomplished life, including a video, have been preserved by Presbyterian Historical Society here.

Adair was born at midnight on Aug. 29, 1920, in Iron Station, North Carolina. Soon after her birth, her family moved to Kings Mountain, North Carolina. “I did have the great gift of knowing my great-grandmother, who lived to be 120,” Adair says on the video.

Her father had seven brothers. Seven of the eight Davidson brothers grew up to be Baptist ministers, including her father. “He was not only Black clergy — he was an educator,” Adair said. “The home of the minister became the gathering spot for educators.” Her father, Robert Davidson, was president and superintendent of Western Union Baptist Academy. “I’m sure that shaped who I am today,” she said in 2019.

Her mother, Violet Wilson Davidson, was a teacher and community organizer.

Thelma completed her studies at Lincoln Academy in Kings Mountain in 1934, then earned degrees from Barber-Scotia College and Bennett College. In 1940, she married the Rev. Dr. Arthur Eugene Adair, and they raised their three children in New York City, where he was pastor of Mount Morris Presbyterian Church.

She organized and directed daycare centers and Head Start programs for the children of migrant farm workers and for the children of working parents in New York City. As a specialist in early childhood education, she also wrote numerous books and articles that would become resources for educators around the country.

She earned a master’s degree and a Doctor of Education from Teachers College at Columbia University. She was named professor emeritus of City University of New York after serving 31 years as Professor of Education at Queens College. In 1944, she helped organize Mount Morris United Presbyterian Church’s Project Uplift, which grew into the Arthur Eugene Adair Community Life Center Head Start program.

“As an educator, I have been very concerned about the educational experiences provided for our children and youth,” she said. “It’s important it be structured and that it reflects the values of the home and the school that would carry them ‘through many dangers, toils and snares.’”

Adair’s many articles and books became authoritative guides to early childhood educators around the country.

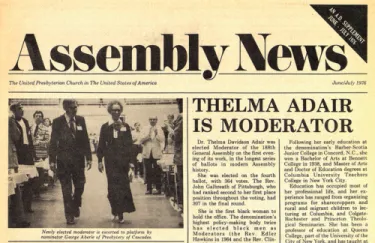

In 1976, she was elected Moderator of the 188th General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

“If we’re going to follow Jesus Christ, we are following a radical,” she told the Assembly, meeting in Baltimore. “We’re following a man who spoke out, acted and lived in a radical way.”

“You are not helpless,” she told the Assembly. “You have power as an individual, and you have power you can find and possess as a group. There are avenues of action. Don’t go home apathetic,” she urged those in attendance. “Go home radicalized by your faith, if you follow Jesus Christ.”

From 1980 through 1984, Adair served as president of Church Women United, a Christian women’s movement working for world peace and justice. Over four years, she traveled to many countries and helped to organize a peace rally held in Central Park on June 12, 1982, which was attended by an estimated one million people.

During her time as president of Church Women United, she set forth important ideas that were progressive for their time. She emphasized uplifting local voices, recognizing that American women could not assume to be experts in solving problems in other countries. She also encouraged women to build lasting friendships with their fellow Christian women in other countries, creating a mutually beneficial partnership.

“Without Church Women United, I would know only Presbyterian women,” she said. “Through the movement, we were able to know women of 28 denominations,” as well as Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox women. She recalled women “putting aside our tiny bickerings and focusing upon the things that mattered: a better life for children, clean water and the support of groups around the world that were bringing together their gifts. The joint gifts of thousands and millions of women in a simple way created paths of change.”

She was a teacher and consultant with the Peace Corps, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and Operation Crossroads Africa.

“Continue the hope and the dream,” Adair advised. “Document the struggle and create the plans for the future. You do that only by knowing how we got over it. You do that by having available those bits of history that create the map of the future.”

“You can’t do it unless you preserve that which we have experienced,” by becoming “fervent, fervent collectors of the past,” Adair said. “This is the rock bed of what my four-year-old great-grandson likes to sing: ‘Don’t let nobody,’ he says, ‘turn you around.’”

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.