Appalachia’s song is a hymn, not an elegy

Inclusive Christian community brings spirit of Appalachia to flatlanders

UNION GROVE, North Carolina — Appalachia has long captured the imaginations of missionaries and politicians in the history of the United States. The selection of U.S. Senator J.D. Vance, author of the book “Hillbilly Elegy,” as the Republican vice presidential nominee reinforces how strong the Appalachian myth is in the American consciousness. The campaign to save the soul of America by responding to the plight of Appalachia began in the 1870s with Protestant missionaries. That fervor continues into this century, mostly through political rhetoric that does not reflect the full humanity of the people of the region.

The Wild Goose Christian Community (WGCC), a new worshiping community located in Abingdon Presbytery in Virginia and supported by the PC(USA)’s 1001 New Worshiping Communities, has its own song to sing and story to tell about God’s presence in the mountains of Appalachia.

The welcome statement on its website states that Wild Goose is a nontraditional worshiping community reaching out to those who might never darken the door of a traditional church.

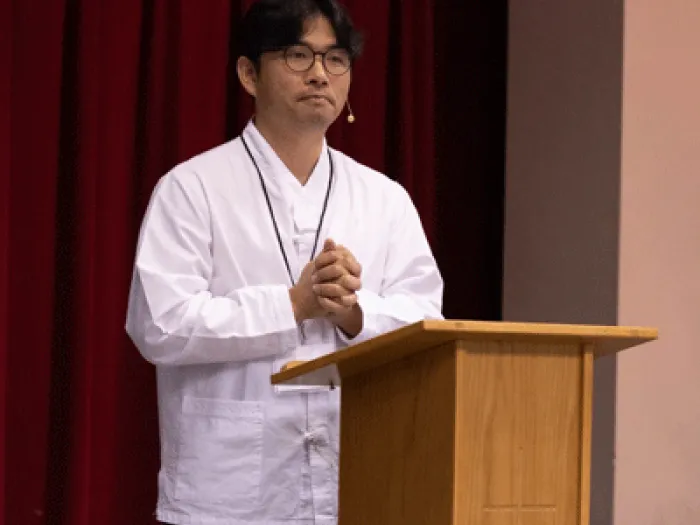

The church has embraced what its pastor, the Rev. Grace Kim, calls the “Goose on the Loose,” bringing a style of worship and a story of mutual care amid diverse beliefs to other communities. Kim explained that this move was not easy because of the history of exploitation of Appalachia’s resources and identity by the rest of America — for economic or political gain. “Through the coal and lumber industries, mountain people have been exploited by outsiders. That has led to suspicion of flatlanders,” said Kim, who was met with resistance the first time she proposed that church members leave the mountains to share their worship and tell their own story.

On July 13, members of the WGCC traveled over two hours down steep, winding roads to share their unique style of worship and inclusive community with pilgrims at the Wild Goose Festival, a four-day festival of faith, music, justice and the arts that took place in Union Grove, North Carolina. Though they share the same name, the festival and church formed independently. Both names are inspired by the Celtic depiction of the Holy Spirit as a wild goose. “The goose is wilder than a dove,” explained a WGCC member. “At times, it’ll bite you in the butt.”

Kim is the second pastor called to the role of “Lead Honker” of the WGCC. She spends two Sundays there and two with another church she serves. Her husband also pastors a church in Bristol, Tennessee, where the family lives. When Kim is away, the Rev. Rebecca Taylor, pastor of Hillsville Presbyterian Church, and others act as “substitute honkers.”

Kim embraced a shared approach to worship leadership for cultural and practical reasons. “People ask me, ‘What is this Korean woman pastor doing in Appalachia?’” said Kim, who immigrated from Korea to earn a graduate degree at Union Presbyterian Seminary in Richmond, Virginia. “I told them, ‘I can only be who I am, and I hope you will be fully who you are.’”

She described the ways she and the community find common ground. “My people identify themselves as Scottish descendants, and they still keep their strong identity with their Scottish lineage,” said Kim. Along with the Celtic symbol of the goose, the Scots-Appalachian identity is also expressed in how they approach music. “Music does not just add to the service, but is the heart of worship,” said Kim, who explained why the community sits in a circle for worship: “Music for Appalachians is not performance. It is music you participate in.” This understanding explains why the community’s name for a worship service, “uprising,” fits so well and why the other parts of the service, from the welcoming icebreaker and the meditative prayer to the shared reflection on Scripture, feel like a harmonious practice rather than a solo act.

During the “uprising” at the festival, 25 people gathered in the hot sun under a white tent in the flat farmlands of central North Carolina. Members of the church gave more details about worship in their own context.

“This is a mini version of us,” said Susan Slate, a young adult member. Slate grew up in neighboring Carroll County but now lives in Blacksburg and works at Virginia Tech. She commutes an hour to the church; WGCC is in Indian Valley, Virginia, in Floyd County. Highway 221 is the closest major road. When trying to explain the location, she said, “You have to mean to get there.” Along with the music, a major draw to some members is that it is one of very few open and affirming churches in the area.

Slate leads the meditative prayer every week, a part of the worship she calls “sit in a spell.” She explained how the congregation usually sits in rocking chairs in a circle and takes communion out of a Mason jar. “We try to pull in as many Appalachian traditions as we can.”

During the service, WGCC musicians known as Mac and the Geese pluck out the notes of praise on a banjo, fiddle and guitar as the congregation sings selections from the “Old Time Gospel Song Book.” Their hymns are arranged in the mountain musical style. The final hymn is always presented in a kind of call-and-response format called “hymn lining,” a tradition that has been traced back to when copies of hymnals and literacy were rare in American churches in the 17th and 18th centuries. The precentor — in this case, Mac the guitarist — quickly calls out each line of the hymn before the congregation follows in the slower pace of the melody.

The gracious back and forth of line singing underscores the compassionate communication that happens around the circle as people engage language and try to translate their thoughts about Scripture and God’s presence into words.

“I love language,” said Kim, who explained that this was something that also inspires the community. To each service, Kim brings Greek and Hebrew word studies related to the chosen texts. Kim described how this kind of investigation into the Bible particularly excites her members who have never earned a degree. She also consults various English translations of the Bible, like the “First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament,” that she used for the festival’s uprising. In this version of John 3:1–17, the meaning of each character’s name is given. Nicodemus is “Conquers the People, ”Jesus is “Creator Sets Free,” the Pharisees are “Separated Ones,” and Israel is “Wrestles with Creator.”

After the Scripture was read, the group was invited to respond. Within this conversation, Kim gave a few insights on the translation and explained how some cultures, like her own, emphasize the meaning behind their names. For example, her Korean name means “Grace,” which is why she is called by this English word rather than her given Korean name. Kim’s own life story as an immigrant and a woman pastor in a conservative area models a resilient faith in a community that has often felt the pain of one’s identity and story being mistranslated and misappropriated.

According to the Rev. Nikki Collins, coordinator of 1001 New Worshiping Communities, Kim is successful in serving a community in a context so different from her own because she adopts a “posture and spirit of learning.”

“I think the larger church could learn a lot from Grace’s example,” said Collins.

The “Goose on the Loose” uprisings spread that spirit of learning when the WGCC goes on the road.

Under the festival tent, Mac and the Geese played an encore at the end of the uprising with a hymn called “Farther Along.” Rather than lamenting the present reality, it praises a God that is greater than disagreements and makes peace with what can and can’t be known for certain.

“Farther along we’ll know all about it, farther along we’ll understand why. Cheer up, my [siblings], live in the sunshine, we’ll understand it all by and by.”

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.