The only Christian hospital in Gaza, Al Ahli Hospital was organized in 1882 by the Anglican Diocese of Jerusalem. In the aftermath of the 1948 war and Egyptian occupation of Gaza, the hospital was operated by the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society. The Baptists withdrew in 1982, a century after the hospital's founding, and an international coalition of funders stepped in, among them Church World Service, Dan-Church-Aid, and the PC(USA). Records in PHS collections shed light on the church’s oversight and scrutiny of Al Ahli, and offer a few insights on Presbyterian accompaniment with Gaza’s people.

As revealed in their words, American Presbyterians encountered Gaza in the context of two hundred years of Christian Zionism, and wittingly and unwittingly disclosed that influence, in spite of their efforts to do good works in the world.

Gwen Crawley, PC(USA) Associate for Health Ministries, visited Gaza in March 1985, and described an untroubled landscape:

“The scenery changed from the high rock hills near Jerusalem to flat groves of fragrant orange trees as we neared Gaza. There were few cars on the road and we were not stopped at the check points. Even though there was some apprehension about Land Day, there were almost no soldiers evident except when we passed army bases.” Even in the 1980s, citriculture had been dramatically impacted by Israeli ecocide; by the 2010s even the crops that replaced oranges were subject to "herbicidal warfare."

In a passage reminiscent of 19th century Protestant pilgrims, Crawley continues, tying the land and its people back to the Christian Old Testament, making the present day people and their political and social struggle comprehensible to her stateside audience through the lens of the Bible: “Historically Gaza is where Samson slayed the Philistines, was tricked by Delilah and finally destroyed both himself and many Philistines when his strength returned.”

Later readers will recognize the “Samson Option” as the name of Israel’s theorized self-destructive nuclear deterrent developed in the 1960s, according to Israeli historian Avner Cohen. Shimon Peres referred to it alternately as, “an option for a rainy day.”

Crawley notes that Al Ahli’s urology department is “an important specialty in a country with a high rate of kidney stones, gall bladder and prostrate [sic] problems due to the Moslem [sic] custom of fasting in hot weather, with little or no liquid intake, and high consumption of nuts in their diet.” This turned out to be a misconception. For one thing, the holy month of Ramadan moves around the solar calendar—this year it’s right now; currently, highs are in the 70s for Gaza, lows in the 50s. For another, even people with chronic kidney disease can with doctors' supervision undertake the fasting/feasting pattern observed in Ramadan. Though noting that more research is welcome, the authors of a 2014 study in the Journal of Research in Medical Sciences find “no evidences that Ramadan is injurious for patients with CKD willing to fast,” even encouraging doctors to take into account the medical benefits of religious practice for people with chronic kidney disease.

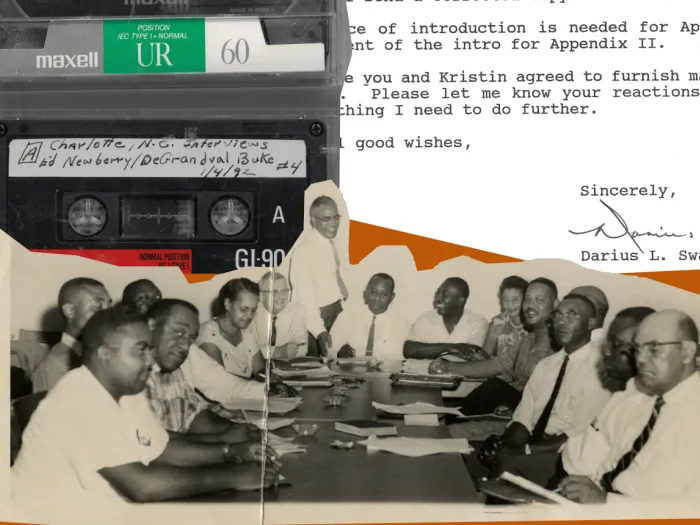

Al Ahli Hospital entrance, 1999, photo by Bob Ellis. From 13-0220, International Health and Development photographs and trip reports, 1994-2001.

In 1985 Al Ahli had just opened new dental and ophthalmological departments, and had an extensive burn unit. Crawley notes, “Open fires, used for cooking in the refugee camps, and kerosene stoves are the cause of severe burns among women and children,” an after-effect of systematic dispossession and displacement.

"The situation is unacceptable to all free people in the world who see human rights and dignity oppressed." —Jens Erik Tranholm, 1987

Apart from the at times mistaken impressions of foreign visitors, what emerges from the records of Al Ahli held in our Church World Service collection is quotidian, normal hospital administration – albeit with the complications of life under Israeli occupation. Olaf Beck, a Dane serving in hospital administration, lays out plays to consolidate outpatient services and retrieve $15,000 in funding recently removed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). He complains about the friction in importing equipment, citing “an ambulance tied up in customs for 2-1/2 years.” There are notes of thanks for monetary support, like the 1985 note from Rt. Rev. Samir Kafity, primate of Jerusalem, to Church World Service for their contribution of $31,000.

There is also gimlet-eyed scrutiny of the necessity of new gifts. Gwen Crawley responds to the same 1985 appeal for funds from Kafity: “This appeal surprises me. When I was at Ahli Arab last spring their budget looked quite well covered. We contribute $9,000 with women’s summer medical and women’s sewing and supply so I don’t feel more is needed now.”

Proposed construction of entirely new building in late 1986 and early 1987 was greeted with cold feet from PC(USA) and NCCC, which wrote to Kafity that “It is our perception that such a proposal, if enacted, would require a renewed commitment of support to the hospital from international partners over the long-term,” and reminded Kafity that the funders are coming to the end of the “transitional period” of five years they’d agreed to back in 1982. Before approving funding, the NCCC asked for answers to a litany of questions drawn up by Crawley—rate of occupancy, amounts paid per bed, which departments lose money, possible cost savings, “Could some hospitalization be reduced with better outpatient or preventive care?”—all of which aimed to limit the costs associated with the hospital.

Peggy Orr Thomas visited Gaza in March 1987 and explained, in part, what’s going on: the Anglican Diocese of Jerusalem is too small to maintain funding for the hospital, and without them it will close permanently.

"If the Anglicans let go of the hospital, the authorities have indicated they will close the hospital and that it will not be allowed to reopen in the future. Gaza is already short of adequate medical facilities, so this is a very serious difficulty.”

Thomas does not specify the authorities in question, but clearly means the Israeli civilian administrative apparatus spun out of military government in the West Bank and Gaza after 1981.

Thomas goes on to answer Crawley’s questions—Ahli is preparing a new agreement with UNRWA that will provide a steady stream of funding; the hospital’s new director is a professional administrator from Denmark, Jens Erik Tranholm, who’s committed to streamlining operations; plans for collaboration with the Anglican hospital in Nablus are afoot; Ahli will specialize in urology and obstetrics/gynecology.

By June of 1987, Bishop Kafity had secured promised redevelopment funds from the German charity EZE, including support for a new building. Plans were set to lease Ahli land to local developers to build a shopping center, which would add a funding stream to the hospital. According to meeting notes, the hospital held five dunams of land in trust, and planned to set aside two of them for commercial development. One quarter of the income created would fund construction of a new multi-story hospital building.

Samir Kafity, in Al Ahli’s 1987 annual report, is the first to mention the Intifada: “Your continued interest and support, especially during the Intifada, made us able to extend our ministry of healing to the young boys and girls who were shot, or whose legs and hands were broken, and the many others who suffered from teargas and plastic bullets.”

Tranholm’s successor, writing in the 1988 annual report, notes how the Intifada changed daily operations at the hospital: “Many things have been changed during the first year of the Intifada in order to meet the needs, not only for the normal patients but also to be able to manage the increasing number of casualties arriving in the hospital.”

Al Ahli Hospital, 1999, photo by Bob Ellis.

Al Ahli survived the crackdown on protests in Gaza, and the PC(USA) kept faith with the hospital, remaining among its institutional donors into 1996. That year, in response to a series of suicide bombings, Israel closed Gaza’s borders, ending transport of commercial and agricultural goods and, according to Al Ahli’s 1996 annual report, shutting off transport of medicine and humanitarian aid.

During the Second Intifada, Al Ahli was designated a frontline hospital for casualties, and its executive director Suhaila Tarazi prepared for Israeli military assaults on Gaza. In a July 2002 interview, Tarazi explained that even without an active shooting war, the hospital never operated without military friction: “Everything is connected to the Israeli military forces and they can stop anything they want. They make no differentiation between humanitarian shipments such as medications and other supplies. It is all tightly controlled and we spend hours working on receiving the things we need to care for those who come to Ahli- sometimes we succeed and sometimes we don't.”

Selections from files on Al Ahli, from 05-0106, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). International Health Ministries records, 1983-2002.

Since the attacks by Hamas on Israeli settlements outside Gaza on October 7, Israel has assaulted Gaza’s hospitals, clinics, and ambulances more than 300 times, per the World Health Organization. The UN’s Permanent Observer on Palestine has said Gaza’s hospitals are “Israel’s primary target.” As of February 23, 2024, Al Ahli was operating at 30% capacity, running entirely on solar power. On March 9, 2024, the World Health Organization reached Al Ahli, delivering trauma supplies and fuel.

The PC(USA) continues to assist the Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem, which oversees Al Ahli. The stated clerk, Bronwen Boswell, has joined other church leaders to call for a ceasefire.

Jens Erik Tranholm, reflecting in 1987 on his 13 months as director, makes an appeal for peace with justice in Palestine that in retrospect is evergreen: “To us it seems to be impossible, but we know it is necessary to find a peaceful solution for all parties with equal human rights for all including the many unhappy refugees in the camps. The situation is unacceptable to all free people in the world who see human rights and dignity oppressed.”

--

Learn more:

Presbyterians and Palestine (2021)

RG 529, Church World Service records, 1911-2000

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.