On Thursday night at Westminster Presbyterian Church, Presbyterian Historical Society (PHS) board director and public historian Tim Hoogland gave an hour-long presentation on the life and legacy of the Rev. David Sindt.

Following the presentation, PHS Executive Director Nancy J. Taylor led a panel discussion reflecting on Sindt’s story and connecting it to the struggles faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals and communities in 2023.

Sindt, who grew up in the Twin Cities and came out as an openly gay pastor in the early 1970s, is remembered today as a groundbreaking figure in the struggle for full inclusion of LGBTQ+ Presbyterians. During the 1974 United Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) General Assembly in Louisville, Sindt held up a sign reading, “Is Anyone Else Out There Gay?” — a “ministry of presence” that Hoogland highlighted at the beginning of the presentation.

Event video courtesy of Westminster Presbyterian Church and PHS, June 22, 2023.

Audience members followed along with a document-based curriculum booklet Hoogland began developing with PHS staff members and friends years ago: “David Sindt and the Fight for the Full Inclusion of LGBTQ Presbyterians in the PC(USA).” The printed booklet includes denominational records from the general PHS collections as well as items collected through the Pam Byers Memorial Collecting Initiative, such as newsletters from groups taking opposing views on inclusion. Hoogland played a recording available through PHS’s Pearl digital repository of a 1972 sermon where Sindt tells worshipers at Lincoln Park Presbyterian Church in Chicago about plans for direct ministry support to the local gay community. The original recording was added to PHS’s collections in 2019 after Lincoln Park provided it and other Sindt-related materials.

Per the research guide for the David Sindt Papers, Lincoln Park’s session had called Sindt “to serve as an assistant pastor and establish an outreach program to the local gay community, but this call was rejected by the Presbytery of Chicago … This was believed to be the first call ever issued to an openly gay man by a Presbyterian congregation.”

Hoogland, a Westminster member, connected that rejection to Sindt’s holding up his now famous sign at the 1974 General Assembly. After leadership within Sindt’s presbytery would not support ministry to the gay community, he took his appeal to the wider church.

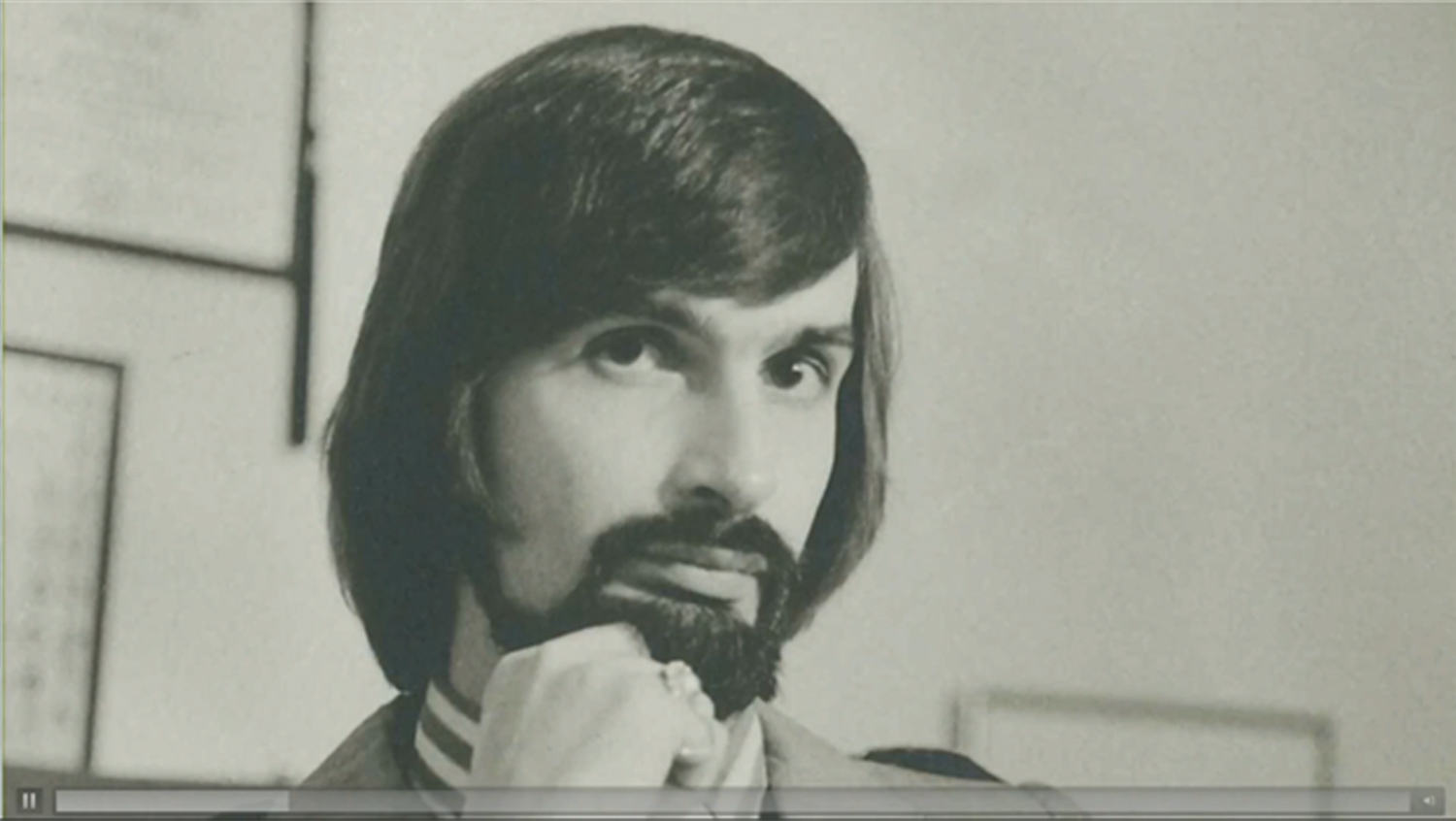

Presentation slide showing David Sindt. All images from June 22, 2023.

Before the presentation, the Westminster audience heard introductory remarks from Westminster’s Senior Pastor the Rev. Dr. Tim Hart-Andersen, Taylor from PHS and Synod Executive and Co-Moderator of the 224th General Assembly Ruling Elder Elona Street-Stewart.

“Histoy is our collective memory,” Street-Stewart said. “It is an exploration of how some see the world and how the world sees them ... We must see oursrelves not only as we are today, but we must see ourselves through time, shaped by relationships and cultural norms that preceded us.

“History always calls us to go back to retrieve the lessons of the past, because truth exists beyond our present time.”

Tim Hoogland presenting from curriculum guide. Photo by Tom Northenscold.

Hoogland, who began the presentation acknowledging that he is not an expert in LGBTQ+ history, thanked the LGBTQ affinity group at Westminster as well as the Hennepin History Museum for helping to publicize the event. He said that a recent email from David Sindt’s sister revealed that the siblings attended Sunday school at Westminster when they were growing up in Minneapolis.

The presentation moved away from Sindt’s story as Hoogland summarized the church debate during the 1980s, 1990s and the first decades of the 21st century related to inclusion, including the Silent Protest at the 1991 General Assembly in Baltimore, polity changes within the PC(USA) and the eventual ordination of LGBTQ pastors. At the end of the presentation, he returned to Sindt’s personal story, and how his death from complications related to HIV/AIDS prevented him from seeing many of the movement’s hard-won victories. A section of the National AIDS Memorial Quilt dedicated to Sindt features irises, a flower he cultivated throughout his life. For the presentation at Westminster, irises had been arranged at the back of the room.

Presentation slide showing David Bailey Sindt section of the National AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Hoogland ended the presentation by asking audience members to fill out a survey, information that he and others at PHS will use to shape the presentation for wider sharing in the future.

The four-person panel moderated by Taylor reflected on individual experiences in the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights inside the denomination and connected changes in church polity to the larger gay rights movement.

Panelists shared what was most personally meaningful about the history covered in the presentation, including appreciation of Sindt’s courage at the 1974 General Assembly and beyond. “Back in the ‘70s it was scary to be gay,” said Terry McEowen, a member of Westminster’s LGBTQ affinity group. “It's very helpful he started the whole process.” Peh Ng, who is active in More Light Presbyterians at a St. Paul congregation, observed that the isolation of a pre-internet world would have made connecting with others in the LGBTQ+ community much more difficult than it is today.

Panel discussion, photo by Tom Northenscold.

The Rev. Lisa Larges, who was mentioned in the presentation as one of the first openly LGBTQ Presbyterians to stand for ordination, called the presentation “very moving to hear and experience.” Like the other panelists, Larges connected the presentation history to the renewed denigration and violence LGBTQIA+ people face in 2023. “Those same methods of oppression — calling a person criminal, sick and sinful — are being used again … We still have work to do.”

Taylor and the panelists also discussed moments of personal joy during the struggle for full inclusion, including same-sex marriages in Westminster’s sanctuary and renewed faith owing to the church’s eventual embrace of LGBTQ+ Presbyterians. “It’s not in spite of the church but because of it that I’m still a Christian,” Ng said.

Larges brought laughter from the audience with a story of a surprising connection between her and an inclusion opponent. After Larges had penned a satirical take on the dispute over inclusion to the PC(USA)’s Presby Web, she received a message from someone telling her “I didn’t think gay people could be funny.”

“It was a moment of crossing a bridge where we both saw each other as having the potential of humor,” Larges added. “Apparently there are funny people everywhere.”

Presentation slide highlighting newsletter stances on LGBTQ inclusion from the 1970s.

Audience remarks and questions focused on Sindt’s early life in ministry and how church polity can address structural realities that make responding to histories of oppression more difficult, including changes to the way the General Assembly debates and discerns.

Echoing Street-Stewart’s introductory remarks, Larges said, “History is remembering but also forgetting, erasing.” She applauded the work PHS is doing “on the remember side and also challenging the erase side” while acknowledging the lingering trauma she feels after years of fighting for inclusion inside the denomination, including judicial hearings where her life was often talked about in terms of legal abstraction.

“That experience of being othered, especially in the church with its spiritual power — it gets to a person after a while,” she said.

In closing the event, Taylor said, “I’m so proud that PHS is able to highlight this history. We want to tell these stories. And we depend on all of you to help us tell these stories.”

Learn More

The David Sindt Papers: https://www.history.pcusa.org/collections/research-tools/guides-archival-collections/rg-521

PHS LGBTQIA+ history timeline: https://www.sutori.com/en/story/timeline-of-lgbtqia-history-in-the-pc-usa

PHS LGBTQIA+ history blog posts: https://www.history.pcusa.org/about/blog/lgbtqia%2B-history