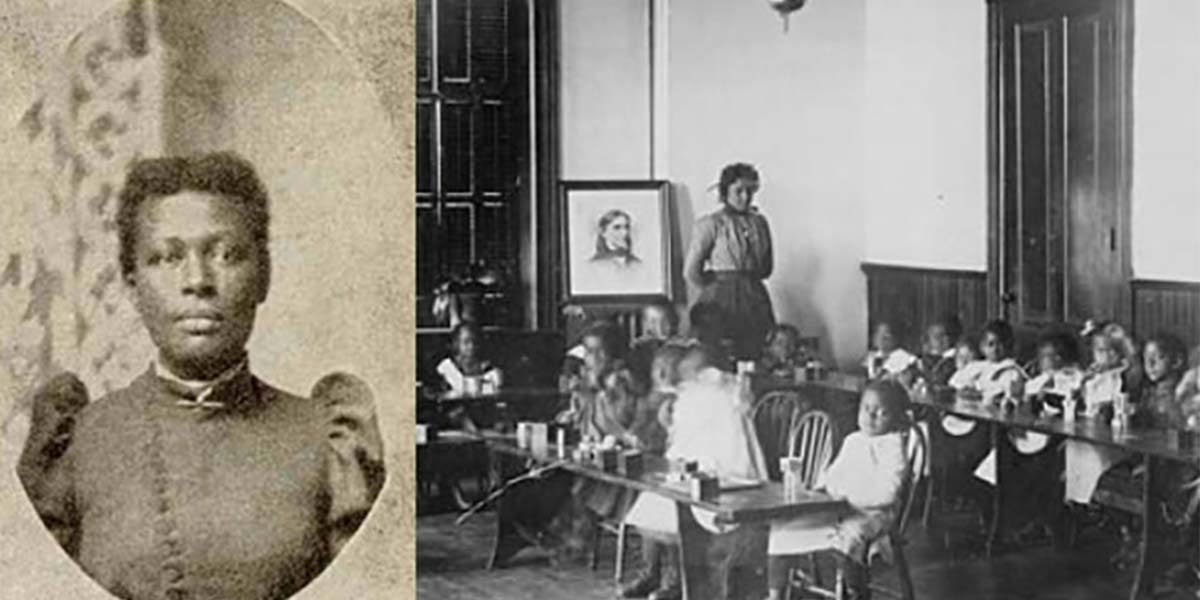

Lucy Craft Laney (left) and a kindergarten class in session at the Haines Institute at the turn of the century. Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The bells of Washington Avenue Presbyterian Church in Macon, Georgia, where Lucy Craft Laney’s father served as pastor, rang at the end of the Civil War in 1865. About four years later, at the age of 15, Laney enrolled as a student at the newly founded Atlanta University, where she would be part of the first graduating class in 1873.

Could she have known, on the day of her graduation, all that laid ahead of her? That a decade from then she would be the founder and principal of a school all her own?

Laney began teaching in the Georgia public school system, with appointments in Macon, Milledgeville and Savannah before settling in Augusta. There, she met the Christ Presbyterian Church community, which saw how she interacted with the local children and convinced her to start a school in their building. The lecture room, typically empty of visitors, was located on the basement floor of the church. It was there that Laney began teaching a group of six children in 1883. Slowly but surely, that number continued to grow. At the end of her second year of teaching in the basement room, Laney had a class of over 200 pupils.

It was in this way that Laney became the founder of the first kindergarten for African American children in Augusta — and, further, one of the first of its kind in the southern United States. Three years after the initial lessons began, Laney’s school became a chartered institution, thanks to the donation of lifetime benefactor Francine E.H. Haines, who gifted Laney $10,000 specifically for the charter. The Haines Normal and Industrial Institute earned its name from its friendly benefactor, Francine.

Three more years passed until her school found a permanent building to call home. In 1889, Laney bought a property at the corner of Robert and Gwinnet streets in Augusta, and was gifted $10,000 for the construction of a building, which would become Marshall Hall. The four-story brick building contained classrooms on its ground floor and dormitories on the remaining floors. In 1906, another check was made out to Laney in the amount of $15,000 for the construction of another building — the four-story brick building, called McGregor Hall, housed the administrative offices and more classrooms.

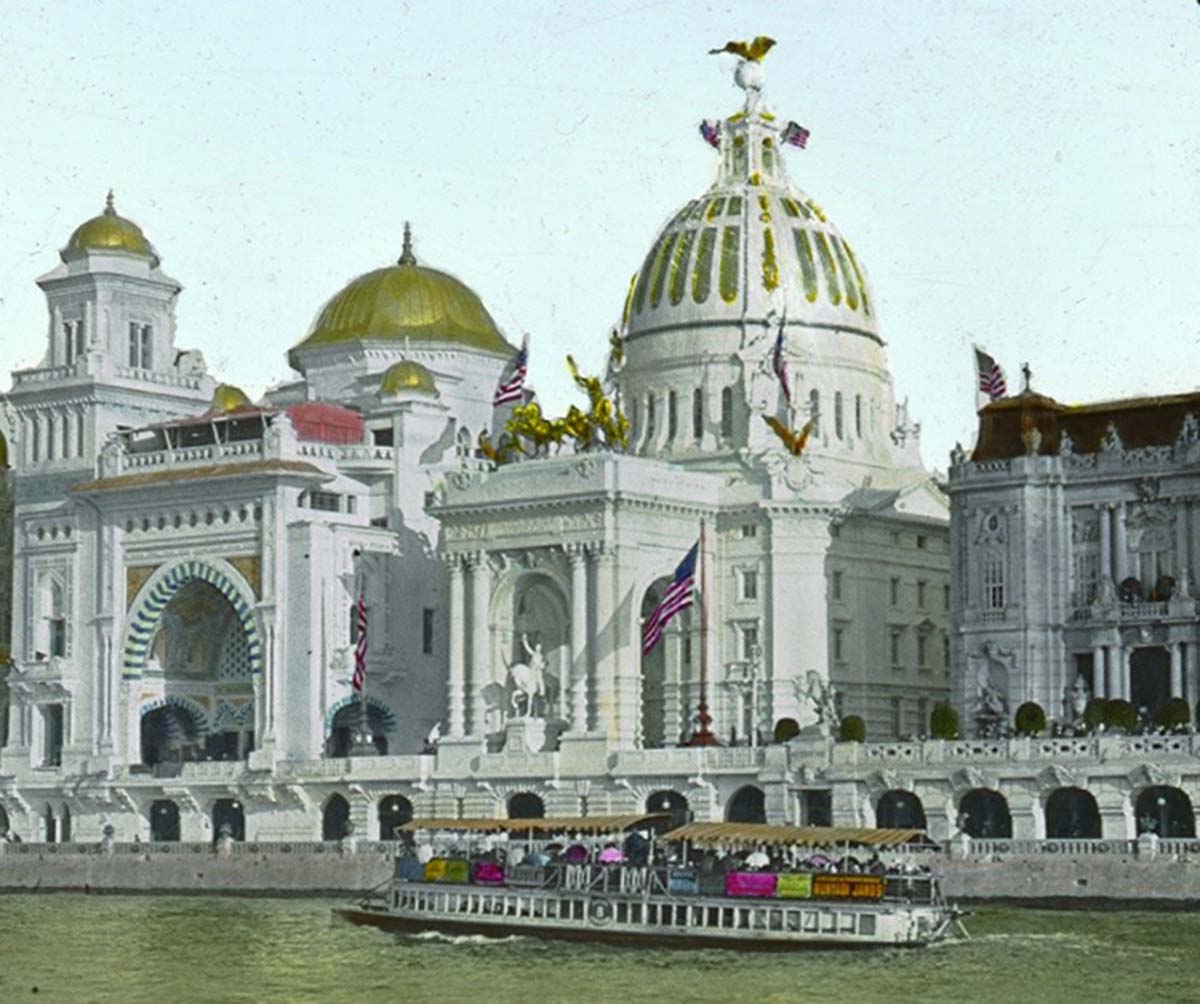

The great success of the Haines Institute was brought to the attention of thousands at the Paris Exposition. The Exposition Universelle of 1900, the last and largest of five expositions held in Paris, worked to highlight the achievements of the 19th century. Millions of visitors walked through the galleries and buildings that housed exhibits of various themes, including the Palace of Civil Engineering, the Palace of Textiles and the Palace of Education. Talking films, a Ferris wheel, moving sidewalks, diesel engines, x-ray machines and the first magnetic audio recorder were listed among the items of wonder at the Exposition.

The American Pavilion building at the Paris Exposition of 1900. Image courtesy of World Fair Magazine.

Among the galleries was a building devoted to matters of “social economy.” W. E. B. DuBois had curated an exhibit in this building that attempted to show “the history of the American Negro,” “his present condition,” “his education,” [and] “his literature.” DuBois, working with the special agent assigned by the U.S. for the Exposition, gathered a total of 500 photos, 32 charts and maps and 200 books to display.

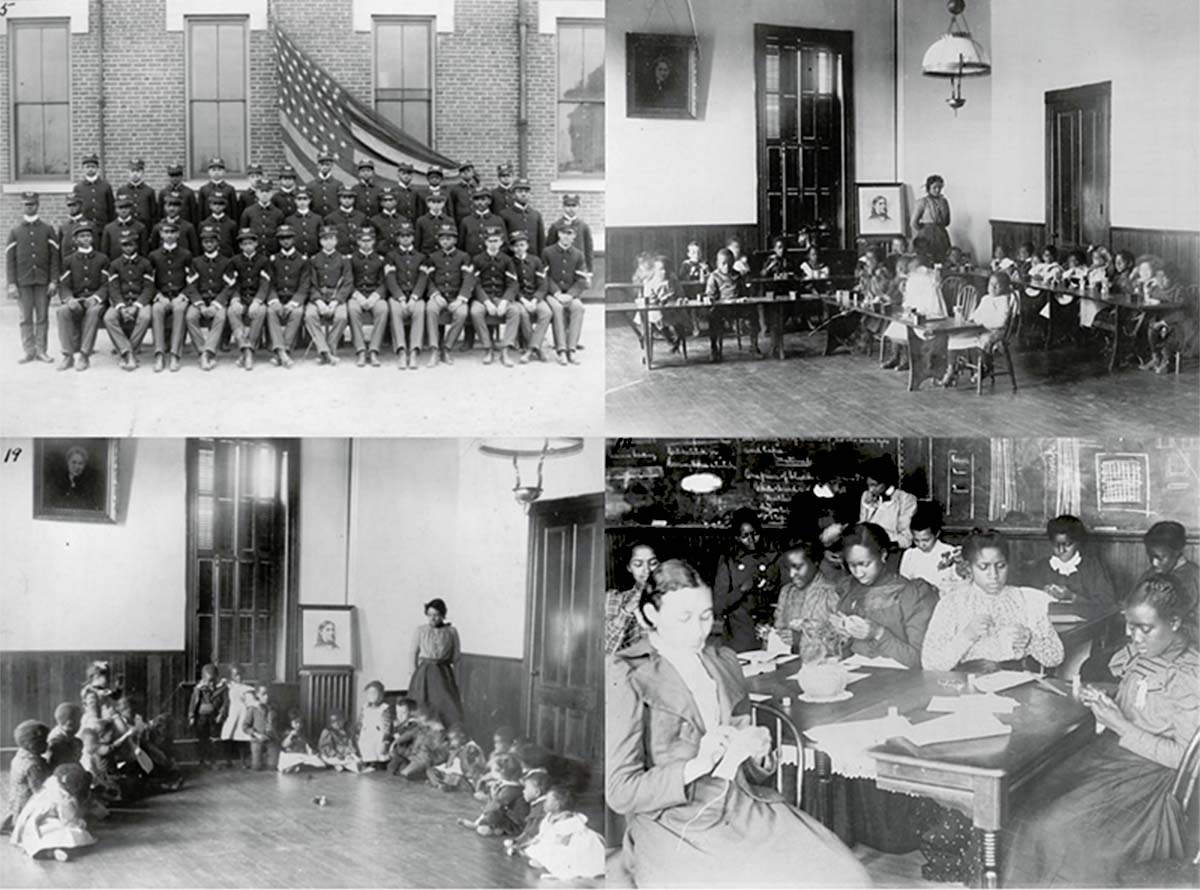

The Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, Shaw University in North Carolina, Roger Williams University in Rhode Island and the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia were accounted for within the photo collection. Placed alongside these other educational institutions were photographs taken at the Haines Institute that showed various classes in session, as well as a group of young cadets.

Photographs of the Haines Institute collected for the Paris Exposition. Group photo of cadets outside of the Institute, top left; kindergarten classes, top right and bottom left; sewing class, bottom right. Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1909, President William Howard Taft visited the school grounds. At the completion of his tour of the institution, he declared that he “had seen nothing in the way of efficiency and of self-sacrifice that could compare with the work of Miss Laney.” In 1912, 26 years after its founding in 1886, the Haines Institute had a staff of 34 teachers and a student body of over 900.

As the years passed, the Haines Institute continued to develop and grow into a highly respected academic institution. Its curriculum grew to include kindergarten, junior high and a nursing school, which was the first nurse training institute for African American girls. The title “Normal and Industrial Institute” speaks to the focus of the classes offered there; the “Normal Department” is what the teacher’s training classes were referred to at the time. Along with offering nursing and education curricula, the Institute taught traditional arts and sciences courses, as well as job-training and vocational-specific programming.

Lucy Craft Laney passed away in October 1933. The memory of her life lives on in a variety of ways. A painted portrait of her can be seen on the walls of the Georgia State Capitol building next to the likenesses of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr and the Rev. Henry McNeal Turner. In 1949, Laney High School opened on the original Haines Institute campus; the street it sits on is named Laney Walker Boulevard. The Cauley-Wheeler Building that housed the primary school of the Haines Institute was the last remaining original structure from the campus for decades until it was demolished in 2014. A historical marker was unveiled in 2009 in front of the Laney High School building that speaks to the history of the Institute, and the continuing ripple effect of Laney’s legacy. Laney herself lies buried on the campus of her school.

Laney’s legacy reamains connected with organizations other than the Haines Institute. In 1918, she was a founding member of the Augusta branch of the NAACP. Laney attended meetings of the Interracial Commission, the National Association of Colored Women and the Niagara Movement. Along with serving as the principal of her school, she was director of the African American community’s cultural center in Augusta. Laney was often referred to as “the mother of the children of the people,” and her commitment to her pupils, to the growth of her community and to the friends she made along the way served as evidence of this title.

A teacher through-and-through, Laney is quoted as saying, "God has nothing to make men and women out of but boys and girls."

This article first appeared as a Presbyterian Historical Society blog post:

www.history.pcusa.org/blog/2022/03/lucy-craft-laney-and-haines-institute

Learn More about Lucy Craft Laney:

Batesel, Paul. “Haines Normal and Industrial Institute, Augusta, Georgia, 1886-1949.” https://www.lostcolleges.com/haines-institute

Jones, A. “Lucy Craft Laney (1854-1933).” November 15, 2017. BlackPast. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/laney-lucy-craft-1854-1933/

Leslie, Kent Anderson. “Lucy Craft Laney.” March 10, 2003. Last edited July 21, 2020. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/education/lucy-craft-laney-1854-1933/

“Lucy Craft Laney.” Georgia Women of Achievement. https://www.georgiawomen.org/lucy-craft-laney