In the mid-1980s, Trinity Presbyterian Church in Tacoma, Washington, was on life support, and Olympia Presbytery had begun nudging the session to consider pulling the plug.

Drugs, crime, and gangs had infested the church’s deteriorating neighborhood. A handful of loyal members attended worship and struggled to maintain the church building.

“But something surprising happened,” says the church’s current pastor, Matt Robbins-Ghormley. “Resurrection happened.” As he describes it, the congregation went from being “on the brink of extinction” to becoming energized through mission in the community.

Last year, Trinity reported 375 “total adherents” (including active members, baptized members, and other regular attendees) and a gain of 19 new members. The number of children in the congregation has grown over the past decade from 30 to 130, and 70 adults are involved in Trinity’s ministries with children and youth.

“The people who have been here a while just shake their heads in amazement,” Robbins-Ghormley says.

One of those long-time members is 87-year-old Irene Orando, who joined the church in 1945. She has remained active in the congregation as it hit rock-bottom and bounced back again.

Orando recalls that once in the mid-1980s she was the only person to show up for Wednesday-night prayer meeting. As she waited hoping others would arrive, she looked around at all the church’s empty classrooms. Finally, she says, “I just stayed and prayed by myself—that we would have people here, that others would come.”

And gradually, the people began to come. Youth With a Mission began using Trinity as a base for outreach to the community. The energy for mission demonstrated by these teens inspired the tiny congregation.

“It was encouraging to us to have them here,” Orando says. “After they left, we thought, ‘What are we going to do now?’ So we got together a task force to see what we could do for the community.”

They came up with two ministries: a tutoring program, in partnership with nearby Bryant Elementary, and a weekly “soup & conversation” gathering to build relationships with people in the neighborhood. “We let people come in and tell us what their needs were,” Orando explains.

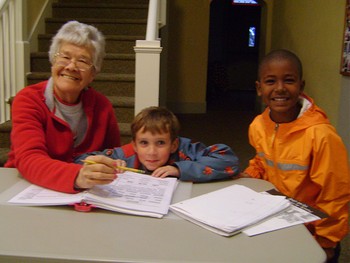

Irene Orando with two kids at the Trinity Afterschool Program in 2012.

Lynn Longfield became pastor of Trinity just as the congregation was beginning to rebound. “When I first came, there was a core of about thirty people,” she recalls. “The thing that struck me was how courageous they were. It took a lot of courage to stay in this neighborhood.

“God had given us everything we needed to thrive,” she continues. “We had folks with a huge heart for the struggles of poverty. We had talent, purpose, and faith. What we needed was to open our eyes to what God’s Spirit was doing and not get in the way.”

“We found we had people in our congregation who were well-suited to do what needed to be done and willing to give their time,” Orando says. One of those was Hazel Pflugmacher, a retired elementary school principal, who was living in a local retirement home.

“Hazel filled her car with retired teachers” and brought them to help with Trinity’s tutoring program, Orando recalls. Orando herself tutored for twenty-eight years, until giving it up two years ago. She still knits sweaters for every new baby in the congregation—sometimes as many as fourteen a year.

Longfield remembers her installation as Trinity’s pastor in the late 1980s. Paul McCann, executive of Olympia Presbytery at the time, gave the charge to the congregation. Noting the signs of renewed vitality as well as the challenges, he told Trinity members, “The future is going to be a roller-coaster. Here’s what you have to do: ‘Buckle up, hold on tight, and pray like crazy.’”

“That became our rallying cry,” Longfield says. “We put it on a big banner and hung it in the sanctuary.”

Ministries and partnerships multiplied quickly, once the congregation stepped out in faith and began engaging with the community. “Things happened so fast,” says Orando, using a metaphor similar to McCann’s. “It was like we were on a river with very strong rapids, and we were swept along by it.

Trinity Staff Member Iris Jackson welcomes guests with a meal and clothing every Thursday night at Pat's Closet

A clothes closet was organized. People from other area congregations came as short-term “missionaries” to lend a hand. University Place Presbyterian Church set up a medical clinic in Trinity’s old manse. The congregation received a redevelopment grant from the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and support from several nonprofits and corporations.

Harlan Shoop became pastor of Trinity in 2000, a few years after Longfield left to become executive of Olympia Presbytery. He recruited a cadre of students from the University of Puget Sound to help with ministries at Trinity.

Welcoming all these new people was a challenge for the small congregation, Longfield says. “It could have been their undoing. But their sense of vision, their trust that this was something God was doing, made all the difference in the world.”

Trinity’s mission statement says the congregation seeks to be “a transformational presence” in its community. This means not just doing things for needy people but listening and building relationships, Robbins-Ghormley says.

“We want to be humble learners alongside our neighbors as well. We also are being transformed.”

Last fall, as Trinity celebrated its 125th anniversary, it launched a $3.1 million capital campaign to restore its building. This will include transforming the lower level into a “neighborhood center” for the congregation’s growing outreach ministries. In phase one of the campaign, seventy member households pledged $1.2 million, Robbins-Ghormley says. Phase two of the campaign seeks funding partners beyond the congregation.

“An outward-looking vision” is key to Trinity’s continued vitality, Robbins-Ghormley believes. “The gospel is never about perpetuating our own institutions. It’s about getting involved with others in word and deed, working for justice, getting to know neighbors—and not being obsessed with our own survival.”

In new-member classes, he asks people what drew them to Trinity Presbyterian Church. Many say, “This is a congregation that puts faith into action. I want to be part of a church like that.”