While the nation may focus on presidential politics in 2016, there is another contest on the same four-year cycle that captures the attention of many Presbyterians—the nomination and election of a Stated Clerk of the General Assembly to serve, in the words of the current job description, as chief ecclesiastical officer of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). This June, the 222nd General Assembly in Portland, Oregon, will elect a Stated Clerk to succeed Gradye Parsons, who is not standing for another term.

According to Carol McDonald, retired Executive of the Synod of Lincoln Trails, and Moderator of the Stated Clerk Nomination Committee, the process of nominating a new Stated Clerk has gone smoothly, with the committee working diligently to discern what the church is seeking now in a new office holder. The nine-person committee, which was elected by the General Assembly in 2014 according to a formula stipulated by the General Assembly Manual, will bring directly to the floor the name of J. Herbert Nelson, Director of the Presbyterian Mission Agency’s Office of Public Witness, to stand for election. Nelson will be challenged by one other candidate who made application and was considered by the committee, David Baker, Stated Clerk of Tampa Bay Presbytery. Nominations will occur on Sunday, June 19 and the election will take place on Friday, June 24.

Book of Order, 2015-2017

The most recent Stated Clerk nomination, in 2012, was uncontested, but consensus has hardly been the norm with regards to that process—at least not since reunion in 1983. Indeed, for a church that celebrates doing things in an orderly way, the Stated Clerk nominating process, which has been reworked several times over the past thirty-three years, has often been messy. The elections of a clerk reflect ongoing developments in the church’s understanding of the nature and purpose of the office in the context of changing demographics within the denomination and the reality of the transformed cultural landscape in which the contemporary church, and especially the mainline church, ministers.

A striking feature of Presbyterianism is the way it labels its primary officer “clerk.” Almost nothing is said about the office in the Book of Order, except that each council will elect a clerk. Although authority is understood to exist collegially and corporately in Presbyterian polity, the Stated Clerk is the one individual officer in which significant authority is lodged. His or her duties, spelled out in the General Assembly Manual and the Stated Clerk position description, include four main areas of responsibility: (1) Administration of the Office of the General Assembly, including serving as chief executive officer and maintaining historical records; (2) Ecumenical and interfaith ministries; (3) Upholding the Constitution; and (4) Chief polity officer at meetings of the General Assembly. All these responsibilities are, for each clerk, important. But each individual prioritizes and carries out the responsibilities in different ways, placing his or her own stamp on the office.

In much the same way a presidential nominating and electing process is defined by the individuals running for office and the issues that loom largest in the public’s consideration, so Stated Clerk nominations and elections are gauges of denominational concern—not only about church actions and theology, but about individual candidates.

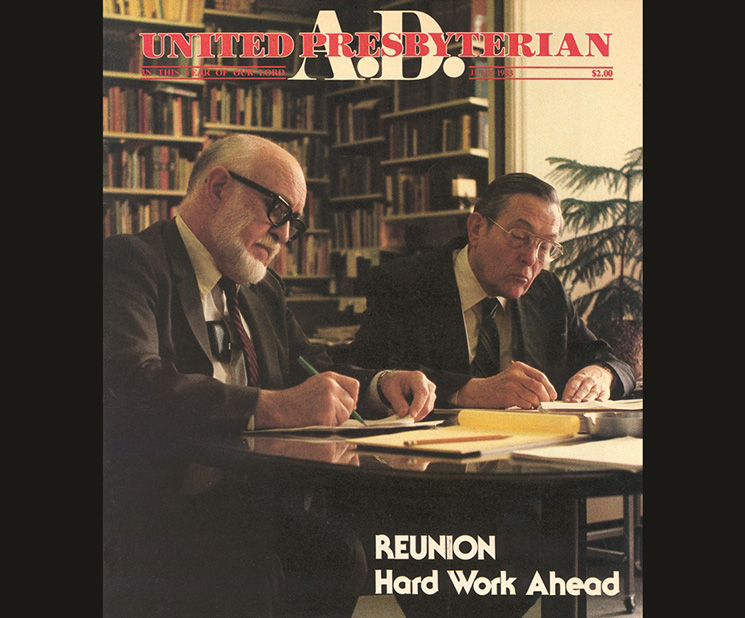

James Andrews and William P. Thompson, 1983

The current shape of the Stated Clerk office had its genesis in the 1983 reunion of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (abbreviated as PCUS and widely referred to as the Southern church) and the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (abbreviated as UPCUSA and widely referred to as the Northern church). Little was said in the Plan of Union, adopted in 1983, about the role of the clerk in a reunited church. The issues of greatest contention were other matters—especially property and freedom of conscience. James Andrews, Stated Clerk of the PCUS from 1973-1983, made a lighthearted comparison between reunion and marriage that was reported in the GA Daily News of June 11, 1983, saying, “You have not finished the job until you have amicably divided the closet space.” Resolving differences in style with regards to the office of Stated Clerk was one of those dividing issues, even if it was not viewed as the most difficult issue to reconcile.

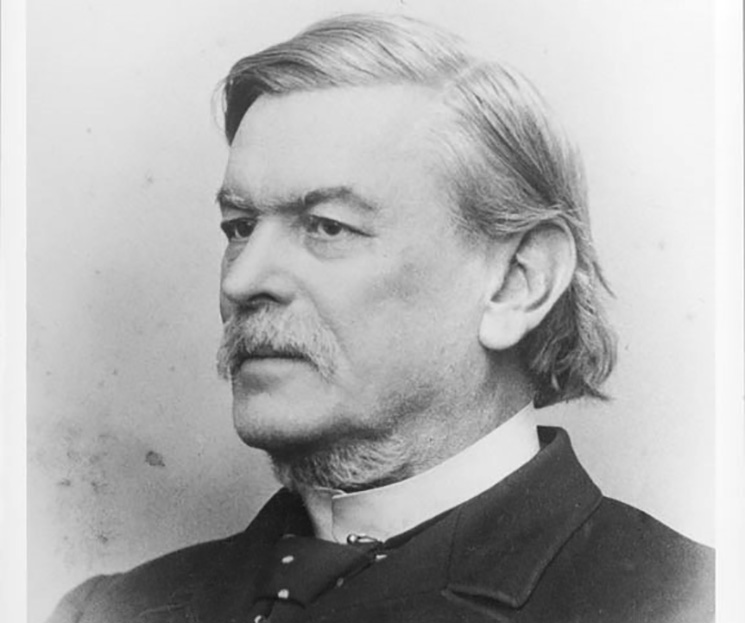

Arrest of Eugene Carson Blake, 1963

According to the terms of reunion, Andrews and UPCUSA Stated Clerk William P. Thompson were to serve as co-Stated Clerks until an election was held in 1984. Both men served as key figures in an Advisory Committee charged with the “Development of the General Assembly Manual and a Position Description for the Stated Clerk.” Once that process was completed, the General Assembly Council appointed a Special Committee on Nominations for Stated Clerk to make a recommendation based on the job description—a recommendation that was then sent to the General Assembly Committee on Nomination of a Stated Clerk during the assembly meeting itself. It was a convoluted process, to say the least, and subject to an array of differing opinions. A review of the records of the Advisory Committee at the Presbyterian Historical Society[2] shows that there were spirited discussions about what they were looking for in a clerk, as well as the election process itself.

The tradition in the Northern church had been for a strong, visible Stated Clerk. Eugene Carson Blake, clerk from 1951-1966, pressed for the church to be engaged with social issues, made national news by being arrested during a 1963 civil rights demonstration in Baltimore, and spoke out against the Vietnam War. Thompson—a lawyer by training who was elected clerk in 1966—followed in that activist role, filing important “friend of the court” briefs.[3] His strong advocacy for civil rights and the cause of peace, as well as his work with the National and World Council of Churches, led the New York Times to call him “one of the world’s most influential religious leaders.” In the Southern tradition, the clerk had been a less visible figure, and the whole administrative structure less top-down, modeling what one long-time administrator with Southern church roots called a “decentralized personalist” approach to Presbyterian polity. Other than Joseph Ruggles Wilson, whose long tenure as clerk from 1865-1898 made him an influential figure in the Southern church, and who is widely remembered today as the father of President Woodrow Wilson, most PCUS clerks acted largely behind the scenes. According to one now-retired Presbytery Stated Clerk who was nurtured in the Southern stream, many in the PCUS tradition viewed the General Assembly Moderator as the figure deserving more visibility than the Stated Clerk, whereas the opposite was true for many in the Northern stream.

Jospeph Ruggles Wilson

Reunifying the nation’s largest Presbyterian denominations was no mean feat. (To compare the clerk nominating process to a presidential one, imagine combining the Republican and Democratic traditions.) To make matters even trickier, societal tensions were mounting during the mid-1980s. Mainline churches, no longer the visible presences of Christianity they had been in the time of great growth during the 1950s and 1960s, were losing members and yielding their public role to other expressions of Christianity, including a resurgent evangelicalism and rejuvenated Catholicism. The widespread emphasis during the Reagan years on smaller, less powerful, and more decentralized institutions was further diminishing to the cultural authority of the mainline churches at the national level.

Historians might debate whether it was the deliberate intention of the Presbyterians who developed the position description for the new Stated Clerk in the early 1980s to temper the power of that office in light of the aforementioned societal forces. But clearly the Special Committee on Nominations for Stated Clerk saw its mandate being the recommendation of a solid but low-key administrator of the kind defined by the newly developed position description. Working toward that goal, the Special Committee nominated Patricia A. McClurg, a well-regarded administrator of the PCUS General Assembly Mission Board, during the 196th General Assembly in 1984. The Assembly Committee on the Nomination of the Stated Clerk declined to take the committee’s suggestion, however, and ended up interviewing four persons before nominating the acting co-clerks Andrews and Thompson to stand for election. (Two other candidates were nominated from the floor, including Robert C. Lamar, former co-chair of the reunion committee.) Thompson held a significant lead after the first ballot, but on the fourth ballot James Andrews prevailed. Perhaps as a way of offering consolation following a stunning defeat, the assembly passed a resolution thanking Thompson for his “dedicated service and gifted leadership” and gave him a standing ovation.

Patricia A. McClurg

The 1984 election was an inauspicious beginning for the Office of Stated Clerk in the reunited church—both to the nominating and electing process, and to the man who assumed the office. That election was the first of three in which Andrews either received no endorsement from the official nominating body or was bested during the initial ballot. All three times (1984, 1988, and 1992) he emerged as clerk.

James Andrews was a competent and personable Stated Clerk, if not the forceful and visionary public figure many wanted. By 1988, there was some desire in the five-year-old united church to replace Andrews, in part because of the church’s handling of various matters of litigation. The Search Commission appointed in 1987 received applications from seven persons as well as Andrews’s end-of-term review. Apparently, the commission did not recommend a particular person for the job but passed the applications on to the Assembly Committee on the Nomination of the Stated Clerk.[4] Because four of the applicants had not yet declared publicly their intention to stand for the office, the Assembly Committee voted to meet in executive session, except for a period of open hearings—a decision that likely contributed to concerns that the process was not open enough. The Assembly Committee unanimously chose to nominate Harriet Nelson, the Moderator of the 1984 General Assembly. But after Andrews was nominated from the floor, he, and not Nelson, was elected in a tight vote, 323 to 298. Some at the assembly felt cheated—if not by the outcome, then by the process. Several commissioners, including the chair of the Assembly Committee, officially protested reporting in the GA Daily News that had suggested the way in which the church nominated the Stated Clerk was “clandestine, top secret, and underhanded.”

James Andrews and Martin Luther King, Sr., 1983

By the time Andrews began considering re-election four years later, in 1992, he was advising his Office of the General Assembly staff that he might not be re-elected and urging their loyalty to the eventual clerk. The church continued to struggle its way toward developing a consistent process that would be open-minded and fair. The Search Commission advertised the clerk position and received three applications. Although the commission members had been asked by the Committee on the Office of the General Assembly to review the entire process leading to the coming election, they reported back that they could not arrive at a consensus, and offered only recommendations about the disposition of commission records.

The Assembly Committee on the Nomination of the Stated Clerk recommended that James Andrews be elected for a third term, but to wide surprise he was defeated on a third ballot by W. Clark Chamberlain, Stated Clerk of the Synod of the Sun. Even more surprising was Chamberlain’s announcement the following day that he could not proceed with installation. It was later revealed that a member of the Office of the General Assembly made assertions regarding sexual harassment that involved Chamberlain. (He would again seek the post, declaring himself a candidate in 1996.) For a short time parliamentary confusion reigned, until it was decided to hold an election between the remaining two candidates, with Andrews prevailing in gaining a third term. After the vote Andrews addressed the assembly, conveying his understanding of the serious concerns expressed during the gathering. The church moved on to other assembly matters, but once again, there was an obvious need to develop a better process for selecting the PC(USA)’s lead officer.

James Andrews decided not to stand for re-election in 1996, thus opening the opportunity for a fresh start. The recast job description for Stated Clerk stressed that “the position...exists for the purpose of helping the General Assembly as the governing body fulfill its goals.” But it was not just an administrative leader the church sought as a new millennium approached. Rather, the job description stressed that “the work of Stated Clerk must be undertaken as a conscious act of discipleship to Jesus Christ. It always bears elements of a pastoral style, both with individuals to whom the clerk relates, and as a spiritual leader for the whole church.”

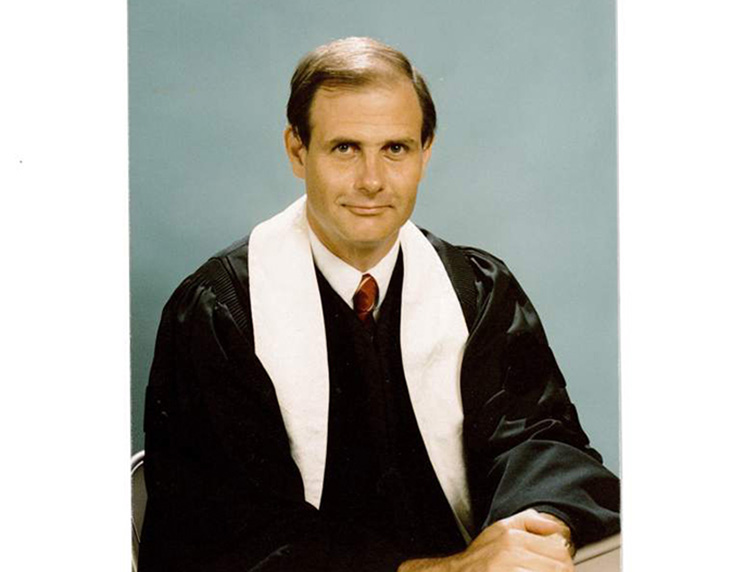

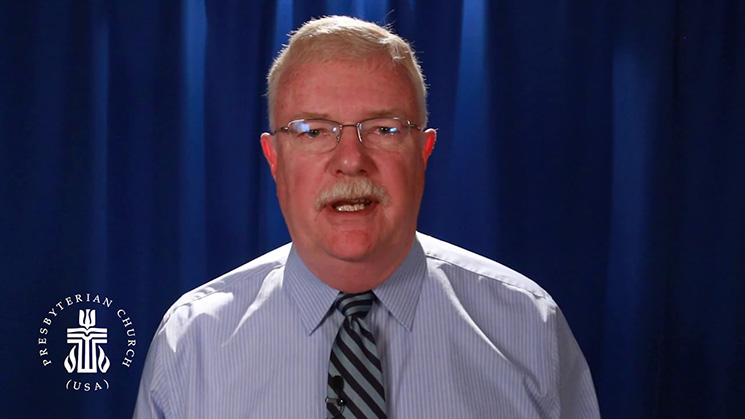

By the 1996 election, the Stated Clerk Review/Nominating Committee understood that its task involved recommending a specific candidate. Culled from a large pool of twenty completed applications, the name it unanimously put forward was Clifton Kirkpatrick, a highly regarded church executive who had administered denominational mission work in the PCUS and then the PC(USA) since 1981. Although the Stated Clerk is elected, the position descriptions make clear it is a job to which one is called. Kirkpatrick, in 1996 and during subsequent elections, stressed to the committee his views on the importance of discerning whether or not God was calling him to this task—both personally and through the voice of the church. The committee had kept open the application process beyond the original deadline and Kirkpatrick put in his papers just before the final deadline.

Clifton Kirkpatrick. Via Presbyterian Outlook, 2016

Four other candidates were nominated at the 1996 assembly, requiring the appointment of an Assembly Committee on Candidate Review to establish a process for reviewing materials and providing adequate opportunity for the candidates to present their positions. The committee this time confirmed the judgment of the Stated Clerk Review/Nominating Committee and endorsed Kirkpatrick. Despite that choice, a disagreement on the Candidate Review Committee about their task, and whether it was authorized to recommend its own candidate as most qualified (superseding the month’s long process of the Stated Clerk Review/Nominating Committee), led to a request that the Committee on the Office of the General Assembly review the entire process as outlined in the Standing Rules. The request was referred to the Committee on the Office of the General Assembly, which recommended standing rule changes.

Kirkpatrick was elected on the first ballot, and by a substantial majority. Soon afterwards, he signaled his intention to be a highly visible clerk. “The clerk needs to be out in the church proclaiming the gospel,” he told the assembly. Internal matters took initial precedence, however, as he and Moderator John Buchanan led a retreat that began the process of easing the somewhat fractious relationships between General Assembly entities. In a church that was even then experiencing budget cuts, membership declines, and division over issues regarding sexuality, Kirkpatrick stressed the importance of unity. Early in his tenure he co-authored the book What Unites Presbyterians: Common Ground for Troubled Times. Having deep roots in mission and ecumenism, Kirkpatrick thrived at those parts of the job and received high marks in those areas during performance reviews. A former Moderator wrote, “[Kirkpatrick] has more gifts in the area of ecumenical relationships than any other.” A colleague affirmed, “[Kirkpatrick] is a giant in this field and should be a source of pride and inspiration.” For the clerk’s part, an ecumenical vision was not just an option, but something “needed in the denomination,” as Kirkpatrick told me in a recent phone interview. It is too easy, he added, to let the denomination fracture “without considering ecumenical implications.”

Reflecting further on his years as Stated Clerk, Kirkpatrick stressed the importance of his role to preserve, defend, and interpret the church’s constitution. During his 2000 self-evaluation, he indicated his intention to lead a church that is “more flexible and open to diversity while clearly grounded in Reformed faith and theology.” Being engaged in public witness, communicating actions of the General Assembly to church and community, addressing issues of polity—these were all part of the process of capturing “a vision of what the church is to be” and what “it means to be the body of Christ, living out the principles of Presbyterianism.”

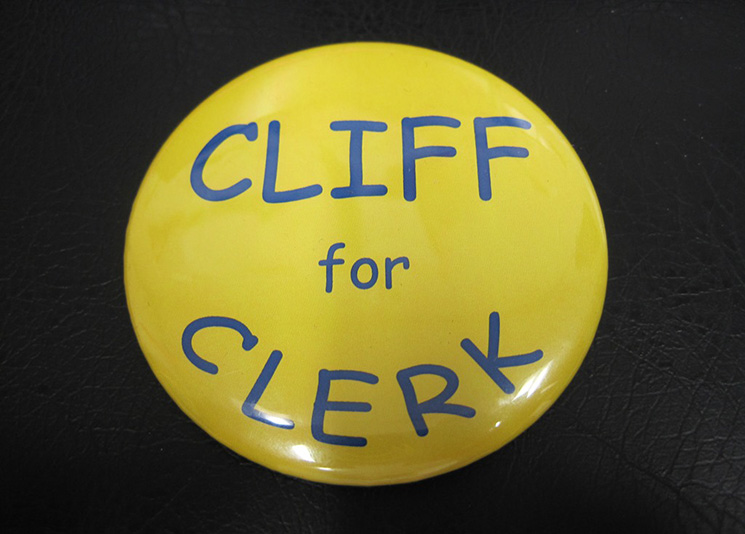

Button supporting Kirkpatrick for Stated Clerk

Kirkpatrick felt a deep sense of call to the office of Stated Clerk and loved the responsibilities of the position, but he admits that standing for election was “an emotionally difficult process.” While acknowledging there is merit in having to face opposition, he hated anything that seemed like self-promotion and still wonders about the wisdom of certain aspects of the nominating and election process.

In the 21st century, those processes continued to undergo refinement, in part because of disturbing developments that occurred during Kirkpatrick’s subsequent elections.

The Stated Clerk Review/Nomination Committee nominated him for a second term in 2000. After an additional nomination was made from the floor, an Assembly Stated Clerk Review Committee—consisting of the Nomination Committee plus ten additional commissioners—was formed again. That body also recommended that Kirkpatrick be elected, which he was by a substantial majority. Despite Kirkpatrick’s continuance in the office, and the sense of continuity his reappointment provided, tensions within the church over the future direction of the PC(USA) complicated matters at the assembly. Winfield “Casey” Jones suggested the church was in crisis and needed a clerk who would deepen the commitment to scripture and confessions and broaden the ecumenical conversation beyond current partners. (Kirkpatrick said he preferred to see the church as a glass "half-full.") Once again the recommendation was made that the Committee on the Office of the General Assembly “review the entire process of the election of a Stated Clerk,” and report back to the 2001 GA, although the minutes of that assembly do not indicate that this happened.

Winfield “Casey” Jones

The election in 2004 was more contentious than the one in 2000, in part because the Stated Clerk’s position became the focus for increasing discontent within the church. The Iraq War had divided the church, as it did the nation, and a commissioner’s resolution called on Kirkpatrick to justify his endorsement of a World Council of Church’s statement on the war.[5] After receiving the Committee on the Office of the General Assembly’s positive assessment, the Stated Clerk Review/Nominations Committee proceeded with its own review, receiving 364 responses, in contrast to only 89 four years before. Although the great majority of responses were positive, affirming Kirkpatrick’s ability to “delineate proper authority for the clerk” and his skill at “grasping vision” for the church, a significant minority of responses raised questions about a range of issues regarding the clerk, including his upholding (or failing to uphold) the constitution and his handling of budget cuts and membership losses.

In 2004, the Stated Clerk Review/Nominations Committee nominated Kirkpatrick for a third term, and three other candidates were nominated from the floor. All voiced concerns about leadership, and one declared rather bluntly that the current clerk “has failed us as a constitutional leader, as a denominational leader, and as an ecumenical leader.” Although Kirkpatrick was again elected, receiving 65 percent of the ballots, his reelection heightened concerns about the fairness of the process. The committee noted that although there were standing rules governing the election of the Moderator, there were none concerning the Stated Clerk; it then recommended that rules be added for future actions. A request made after the election for an “investigation” of the process passed overwhelmingly.

Presbyterian Outlook, August 2004

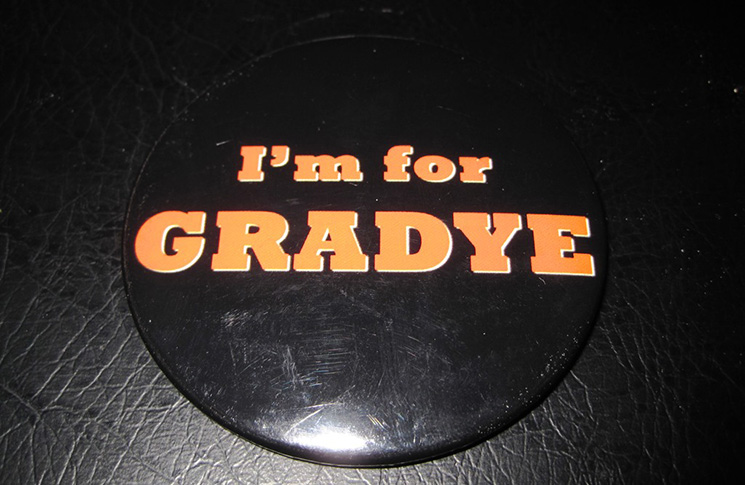

Many saw this as long overdue. The increasingly politicized process was especially visible during the 2004 election. Some raised concerns that “friendly” questions had been planned and fed to candidates in advance, that lists of “endorsements” were circulated, and that advocacy groups were holding strategy sessions and distributing materials (including one decrying Kirkpatrick’s “failed leadership” that was stuffed into commissioners’ boxes). Campaign buttons for and against Kirkpatrick were visible around the assembly. Although such lobbying efforts had long been part of the assembly process in other matters, an article in Presbyterian Outlook from August 2004 shows that numerous Presbyterians questioned whether “resourcing the commissioners” in these ways was appropriate for the election of the Stated Clerk.

Despite the Stated Clerk Election Review Committee examining the process at the 2004 General Assembly and determining it to be fair and open, a major overhaul was approved at the 2006 GA. The review portion of the Stated Clerk Review/Nominating Committee was eliminated and that task re-assigned to the Committee on the Office of the General Assembly (which was already conducting a review, in fact). All applicants for the office were required to submit a Personal Information Form or current resume, and an incumbent wishing to be re-nominated was required to let the committee know of that decision 180 days before the start of the General Assembly. The committee would then interview all applicants and select one as its nominee. Other applicants not chosen who wished to be nominated against the committee’s nominee were to declare their intention 45 days before the opening of the assembly, effectively eliminating last minute nominations of individuals who had not been vetted by the committee. Some committee members, concerned about “self-promotion,” objected to the requirement that candidates make personal application rather than being proposed by others. But that concern was deemed a minor one by most committee members and it did not shape the election process overhaul.

Perhaps the most significant changes were the rules established to prevent anything considered “a campaign for the office of Stated Clerk.” Printed materials provided by the candidates were to be distributed by the Office of the General Assembly only and were to be limited in scope—that meant no flyers, buttons, or other materials distributed by the candidate or by those acting on his or her behalf. Even the candidates’ availability at the meeting prior to the election would be curtailed. The intent was to ensure the office be considered a “calling and not a popularity contest.”

Moderator buttons through the years. From PHS Museum Collection.

While much had been clarified regarding the nomination and election of a Stated Clerk, including the differences between that process and the selection of a Moderator, the 2008 General Assembly showed that significant ambiguities remained to be worked out. Cliff Kirkpatrick’s decision not to seek re-nomination opened the door for a new clerk. Fourteen persons initially applied. After Gradye Parsons—the Associate Stated Clerk for eight years and a Presbytery Executive and long-time pastor before that—received the Stated Clerk Nominating Committee nod, three other candidates indicated their desire to challenge his nomination.

The Stated Clerk Nominating Committee spent considerable effort in 2008 defining the new standing rules adopted at the previous GA. Candidates were to “stand” for election, not “run.” No Presbytery endorsements should be sought, no materials distributed (other than the official six pages authorized by the committee), and no candidates were to accept speaking engagements during the assembly or respond to interview requests unless the same opportunities were afforded to all candidates. Parsons commented at the time that “the standing rules are both very clear and very vague about what is allowed and what is not concerning ‘standing for clerk.’” One of the other candidates expressed concerns along those lines, namely that the committee had used its “discretion to interpret the rules in a way that limits information.” Nevertheless, the committee held firm to its interpretation of the rules, and Parsons was elected by a wide margin on the first ballot.

Since 2008, Parsons has served as Stated Clerk. His tenure has been marked by a number of daunting challenges. Membership decline and budget and staff cuts have been ongoing. Beginning especially with the “Peace, Unity, and Purity” report in 2006 and continuing through the modifications of the constitution eliminating the “fidelity and chastity” clause regarding ordination and permitting same gender marriage, discontent has been registered by congregations desiring to leave the denomination. Parsons told me in a recent phone interview that his office has become a target for much of that discontent, and that it is not easy for him or others in the Office of the General Assembly to deal with such sustained criticism. He understands that being clerk is a “grown up job,” and that “taking a punch goes with the territory.” Despite mounting difficulties, he has demonstrated a pastor’s heart while working to encourage the church to utilize new tools of discernment and other ways of decision making. His deep personal faith, strong roots in Reformed theology and practice, appreciation for the differences among church elders, and sense of humor have gained him unwavering support in many areas of the church.

Parsons acknowledges that much of his work’s effectiveness has depended on developing relationships and building collegiality—areas he considers personal strengths. But he contends that there are certain times when the clerk “needs to be assertive.” The days may be gone when American culture looked to mainline churches as the hub of religious leadership, but Presbyterians still “create leaders.” When issues such as the police shooting in Ferguson emerge, it is important for the church to be a sympathetic voice in national discussions and to engage in actions that are grounded in the policy of the denomination.

Gradye Parsons

Parsons is keenly aware of the changes facing the church and the need to cast a vision for the future. “We’re going to be a different church in light of recent decisions, certainly more open-minded and welcoming. It’s time we claim that this is who we are and not be embarrassed about our social witness.” Acknowledging the pain that comes from separations, he offers hope from a Carly Simon song, “There’s more room in a broken heart.”

A more open church requires new possibilities. Parsons suggests that the church’s future ministry will not be top-down, at the national level or the local church, but rather laity-led; it will also require learning how to lead “from the middle.” While some denominations still prefer the idea of a single corporate leader, Parsons does not think that model is right for Presbyterians. What is? The whole church is trying to figure that out. The answer will likely require a Stated Clerk who is open to new possibilities, seeking to lead not according to a style that worked fifty years ago, but in a way that fits the changing contexts of today and tomorrow. “I remain hopeful about the church’s future,” Parson said, “though its shape may be quite different” than that of the past.

That buoyant spirit, in the face of deeply challenging circumstances, is surely one reason Parsons is the only clerk since the 1983 reunion to run for the office uncontested. (He received the unanimous vote of the 2012 General Assembly.) Another reason is the way some Presbyterians no longer see the clerk’s office as a locus for the kind of denominational transformation they have sought and have placed their energies elsewhere. Parsons describes himself as “humbled” by the former reason; he seems understanding but unperturbed by the latter. “It is a healthy sign that people don’t see that the only way to change the denomination is from Louisville,” he said. Many letters to the Stated Clerk Nominating Committee in 2012 from his General Assembly colleagues were laudatory; “[Parsons] is a superb Stated Clerk who is appropriate for his time” offered one. In presenting him for re-election, the Committee praised his calming presence, his “love for the church” and his belief in “the church God wants us to be.” It also noted with satisfaction the clerk’s deep roots in his local congregation, where he teaches regularly an adult Sunday school class.

Button supporting Parsons for Stated Clerk, 2008

Despite some confusion about the clarity of the rules, for the most part the church seems to have settled into a procedure for nominating and electing a new Stated Clerk that works smoothly and meets the commissioners’ desire for a fair, open process. The church desired and developed a process for this continuing office that is different from the election for the Moderator and the processes for securing executives for the mission agency of the church. The dignity and historic roots of the office make the procedures by which a new Stated Clerk is called of significant importance.

Parsons’s decision in 2015 not to stand for another term generated considerable interest in the office. Thirteen persons submitted applications, including J. Herbert Nelson and David Baker, and six were interviewed. The committee emphasized its desire to consider women and persons from diverse racial, ethnic, and leadership groups. Previous committees had emphasized a similar concern, though only white men have been elected to date, and only one elder.

The committee’s most recent application and interview process was detailed. Each candidate was asked to make (1) a video presentation about “why they should be the nominee,” (2) answer a series of questions about their experiences, (3) evaluate their gifts in the four areas over which the clerk has responsibility, (4) write a statement of faith, and (5) provide five references. Applying required a definite seriousness of intent.

Beginning of Stated Clerk job description, 2016

Any future clerk needs to be prepared for the possibility of structural change. Several overtures before the 2016 General Assembly suggest placing the General Assembly mission and program under the office of the Stated Clerk. There are budgetary and interagency rationales behind this suggestion, and the church has long had a tradition of trying to solve theological and practical challenges with structural and organizational solutions. And yet, historically, the clerk is the public persona of the denomination, with functions that remain distinct from those of the Executive Director of the Presbyterian Mission Agency; a merger of the Presbyterian Mission Agency and the Office of the General Assembly would require a significant change in polity. Whatever the future church structure will be, the new clerk, in the opinion of the Stated Clerk Nomination Committee, has to be prepared to participate in that conversation. Committee Moderator McDonald suggests that this clerk will serve in a time of transition, and undoubtedly help to reshape the denomination.

Though the most recent job description for the Stated Clerk remains largely the same as earlier versions, one conspicuous addition gives the office holder the task of being “cheerleader for the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)”—not in the sense of presenting a rosy view of all things, but by being a positive public presence for the entire denomination.

Hopefully, the 2016 General Assembly in Portland will confirm that we have a sound, fair, and clear process in place for the election of this important officer, and that all things will be done “decently and in order.” However the assembly plays out, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) will soon have a new Stated Clerk, who will take office on August 1 and who will need and covet our encouragement and prayers. The new U.S. President will no doubt warrant the same, but that’s a matter for another time.

[1]Rich Reifsnyder recently retired after 44 years in pastoral ministry in the PC(USA), including 21 years as pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Winchester, Virginia. He is a graduate of Duke University, Yale Divinity School, and Princeton Theological Seminary, where he received a Ph.D. in Church History. Among his publications are articles on the history of church organization and leadership in The Presbyterian Presence series. Rich lives in Salisbury, CT.

[2] A note on sources: Primary sources consulted during the research for this post at the Presbyterian Historical Society are the Minutes of the General Assembly (1983-2012); the Joint Committee on Presbyterian Union Records, the Records of the Advisory Committee on the Development of the GA Manual and a position description for Stated Clerk (1983-84); and the Reports and Records of the Stated Clerk Nominating Committees (with varying names, 1984-2014). Because many of these unprocessed records are restricted, I have been cautious in citing specific identifications.

I also interviewed Stated Clerks Clifton Kirkpatrick and Gradye Parsons, as well as current Stated Clerk Nomination Committee Moderator Carol McDonald.

[3] Thompson had General Assembly action as justification for such amicus briefs, though he was challenged by some within the denomination who thought he overstepped his authority.

[4] A note on name and structure changes to the nominating committees: The committee charged with the task of overseeing the nominating process of the stated clerk was initially called the Search Commission and later the Stated Clerk Review/Nomination Committee (SCRNC). It is elected by the assembly a year before a Stated Clerk’s term ends.

Although the Committee on the Office of the General Assembly did its own end-of-term review of the clerk on a regular basis, this special committee was also given that task, and took its job quite seriously. Input was solicited from among the clerk’s colleagues at the General Assembly, the Stated Clerks of the Presbyteries, other church and ecumenical leaders, and the church as a whole. If the current clerk chose not to be nominated for another term, the committee was charged with the task of conducting a search, including “recruiting, screening, interviewing and selecting a candidate” to nominate. The Committee on the Office of the General Assembly was to provide an updated job description. While initially the Search Commission/Stated Clerk Review/Nomination Committee passed its recommendation of a specific candidate on to an Assembly Committee on the Nomination of the Stated Clerk, in subsequent elections it became unclear if that was the intention or if its mandate was only to collect and screen applications to pass on to the Assembly Committee.

Indeed, exactly how the SCRNC work was to relate to the Assembly Committee was unclear. If the SCRNC did propose a specific candidate after months of work, it was unsettling that the Assembly Committee, meeting only for a few days, might reject that nominee, as happened in 1984. By 1996, the step of having a separate assembly committee was eliminated, and the SCRNC began reporting directed to the assembly.

[5] The Committee on the Office of the General Assembly affirmed that the clerk’s actions were in compliance with the standing rules and were part of his responsibility as clerk.

This article has been republished in its entirety from the Presbyterian Historical Society website.