If the term liturgy more or less translates from the Greek as “the work of the people,” then the congregation of the West Plano (Texas) Presbyterian Church is working overtime—at least for three straight days at the culmination of Holy Week.

For the last 12 years, the 200-member church has wholly embraced the all-consuming practice and the larger, missional significance of celebrating Triduum, “The Great Three Days” of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Vigil, “a single liturgy in three acts.”

“Triduum challenges any pastor in any church,” said the Rev. Dr. David Batchelder, pastor of the congregation. “It’s a lot more work to do this liturgy. If you’re not used to doing it, or if you don’t want to do it, it’s not going to happen. You have to consent to expending yourself.”

Batchelder said that for him—and increasingly for the congregation—observing the three days is not an option, because “liturgical time calls us.” That is, the entire mystery of Christ’s incarnation, life, death, burial, resurrection, and return to God is concentrated and celebrated in this brief time period.

“I can’t help it that this is the way that history played out,” Batchelder said. “’The Great Three Days’ is not historical reenactment, but it does take account of the fact that in these three days is the Paschal mystery.”

The Rev. Dr. David Gambrell, associate for worship in the Presbyterian Mission Agency’s office of Theology and Worship, has called the Triduum the heart of the Christian year.

“In my view, the recovery of the liturgy for the Three Days is one of the most critical and exciting areas for the ongoing reform of Presbyterian worship,” said Gambrell, who—in partnership with the Presbyterian Publishing Corporation, the office of Theology and Worship, and the Presbyterian Association of Musicians—is overseeing a revised edition of the Book of Common Worship to be published by Westminster John Knox Press in 2018. Gambrell serves as co-editor with the Rev. Dr. Kimberly B. Long of Columbia Theological Seminary.

Maundy Thursday foot washing at West Plano (Texas) Presbyterian Church. —Photo provided

“The services for the Three Days are one of the hidden treasures of our Book of Common Worship,“ Gambrell said. “They are deep, rich resources, and unfortunately not very well known, well used, or well understood. These services are designed to be a ‘total immersion’ in Christian faith and life. When a congregation embraces the liturgies for the Three Days it can be an incredible opportunity for Christian formation, renewed discipleship, and spiritual growth.”

When Batchelder, who had previously instituted a celebration of Triduum at the congregation he formerly served in Latrobe, Pa., joined the staff of the West Plano Church in January 2003, he found that the church had an abridged Maundy Thursday service and an observance of Good Friday, but that the Easter vigil had somehow dropped off the church calendar.

“My first step toward restoring the liturgy of Triduum was the restoration of the vigil,” he said. “We brought it back in 2004 and have held it ever since.”

Batchelder described the Easter vigil as “a fully-embodied, multi-sensory, and thoroughly intergenerational liturgy,” around which the West Plano Church now centers its baptismal practices, hearkening back to the early church in particular, when the vigil was the primary annual occasion for baptisms.

“It’s not legislated so that you cannot be baptized at some other time of year, but it was so enticing that there was no resistance at all,” he said. “I have families with little kids that will wait, because there’s just no question that’s when they want their children to be baptized.”

The church’s Easter vigil, which is stational in nature, moves from the parking lot to the fellowship hall to the sanctuary. Batchelder said the unique service is “the high point for the church’s families.”

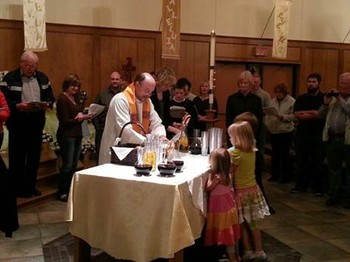

Easter Vigil communion at West Plano (Texas) Presbyterian Church. —Photo provided

Gambrell said that the Easter vigil is an especially good occasion to engage children. “Gathering around a fire and passing out candles, telling stories from Scripture in a great pilgrimage around the church, sprinkling with water or anointing with oil, sharing communion as a truly joyful feast,” he said. “All of this makes for a feast for the senses and a playground for theological imagination.”

Added Batchelder, “Easter Sunday morning is a great liturgy, but after the vigil it’s almost anti-climactic.”

Knowing that not everyone in the church can always make the Easter vigil, which starts after sundown and averages two and a half hours in length, Batchelder said that members always have a choice.

“We don’t apologize for any of this,” he said. “If you’re going to complain about this…you don’t have to be here, or you can come for an hour. This is not about ‘have tos.’ The way the invitation to the congregation is written, nobody is compelled.”

Because Batchelder views Triduum not only as a holistic liturgy of and for the church but also as a metaphor of what the church is called to become, he intentionally introduced the practice of foot washing to the congregation’s Maundy Thursday service, which, for him was the one key element that was missing.

“It was not without some coaxing, because people are funny about their feet,” he said. “There’s also a threshold of intimacy to which some people have a natural reluctance; but on the other hand, that’s kind of what it’s all about. Foot washing is about the vulnerability of the community to one another and in service to the world. Diaconal service is about us being openly for the “other” in ministry, so the very ritual of foot washing draws the community across its resistance and discomfort.”

For Batchelder, engaging the discomfort—as Peter did in John 13:1-17—is part of the intention of Maundy Thursday.

“That’s where we are as churches, right,” he said. “We have to negotiate our discomfort with strangers coming in, people who don’t look like us, people sitting in our favorite places in church. It’s about getting out of ourselves, moving beyond ourselves. So Maundy Thursday—really the whole of Triduum—becomes a living icon of what the church is called to become, and, in that sense, is about the church’s conversion to be more fully its servant self to the world. Every liturgy in that sense, Maundy Thursday included, is a service of wholeness in its own way in the sense that it calls us be more fully who we are created to be.”

Not surprisingly, Batchelder observed, the children of the church lead the way in the ritual of foot washing because they have no inhibitions. “We make space for things in the liturgy that maybe aren’t everyone’s first choice, but we’re thoughtful about not passing on our baggage to the children,” he said. “Just because we didn’t like it, we don’t insist that our children should grow up not liking it.”

Batchelder said that the church now “owns the liturgy” of Triduum in the sense that they’re not doing it because of him, or for him, or because he likes it. “It’s that this is who they are,” he said. “The liturgies themselves, when done well, take hold. What happens is that they then serve as a kind of point of reference from which we can think about what it means to do ministry and mission the rest of the year. We are a people who are marked by this.”

As an example, Batchelder cited an ordination prayer in the PC(USA)’s Book of Occasional Services, which was recently read on Sunday, March 6, when a new class of deacons was ordained, praying that those being ordained “offer a cup of cold water, wash one another’s feet.”

“The liturgy of Triduum awakens people to other allusions in different texts,” he said, “allowing them to ask, ‘What does that look like? What does it mean to wash feet?’ You can have conversations in a mission committee about that. It becomes a metaphor that lives. It’s empowering in that way.”

-----

Read a related article, “The fall and rise of Holy Week,” by David Gambrell. http://pres-outlook.org/2016/03/the-fall-and-rise-of-holy-week/