Even the famously cerebral John Calvin, widely acknowledged as the founder of the Reformed tradition, recognized the arts—music, sculpture, and painting—as “gifts of God.”

In fact, Calvin insisted that Christians employ all of their senses in the service of God, a practice that was second nature to Harold Daniels, one of Calvin’s foremost contemporary heirs in the art of Reformed worship.

Daniels, a celebrated Presbyterian theologian and editor of The Book of Common Worship, who died on February 5 at the age of 87, had amassed—and deeply enjoyed—a considerable collection of liturgical art throughout his lifetime.

“Harold Daniels had a deep appreciation of beauty in life and liturgy,” says David Gambrell, associate for worship for the Presbyterian Mission Agency, “not for the sake of decoration, but for a holy purpose: drawing us into the great mystery of the living God, and opening our eyes to the transforming presence of the risen Christ.”

And in the months prior to Daniels’s death, he remained committed to finding a way for his art to live on in the life of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) He eventually achieved his purpose by gifting his collection—in its entirety—to First Presbyterian Church of Dallas, Texas, a congregation with which he had no formal ties, yet, as a Presbyterian, nevertheless felt deeply connected.

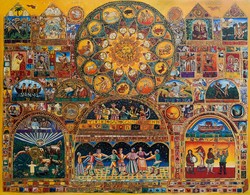

His impressive collection includes works by Sadao Watanabe, Robert Hodgell, and Nalini Jayasarya—all of whom were artists in residence at the Presbyterian Center in Louisville, Ky.—John August Swanson, Jyoti Sahi, and others.

How Daniels ultimately decided upon First Presbyterian to safeguard his legacy is a testament to the power of the connectional church.

As Daniels’s health began to fail, he and his wife Marie met with Hal Hopson, the well-known composer and church musician, and his wife Martha, both “friends” of First Presbyterian. Their daughter, Carol Herriage, chairs the church’s worship council.

Marie Daniels and Joshua Taylor during the delivery. —Sara Ponton

“When Harold asked the Hopsons if they knew of a church that would value and display art, Hal mentioned our church,” recalls Joshua Taylor, the congregation’s director of Worship & Music. “First Presbyterian has a rich history of valuing the arts—visual, musical, and otherwise—in worship. That’s also present in our community ministries, especially the Stewpot open art program, where members of the homeless community participate in art classes. We frequently display the art they create.”

As plans for the gift began to unfold, Taylor says he continually discovered “fascinating intersections” between himself and Harold Daniels, as the two—and Marie—began to talk and exchange letters.

“Even though I grew up a Presbyterian, when I began my career as a church musician, someone recommended to me that if I wanted a deeper understanding of worship in the Presbyterian Church that I pick up a copy of To God Alone Be Glory, Harold’s book that he wrote about The Book of Common Worship,” Taylor says. “I still have that book sitting on my shelf. So when Hal [Hopson] mentioned that Harold might be contacting me to discuss the art, he said, ‘Are you familiar with who Harold Daniels is,’ and I was, because I had read this book and his journal articles, which makes me a Harold Daniels groupie. I don’t think I’m alone in that.”

Taylor also knew Daniels through their shared service to the Presbyterian Association of Musicians (PAM), to which Daniels was given honorary lifetime membership in 1997, and for which Taylor served as a member of the executive board and as conference director for the 2014 Mo-Ranch/PAM Worship & Music Conference.

Daniels also knew Taylor’s name from the columns he had written for Call to Worship, a quarterly journal published by the Presbyterian Mission Agency’s office of Theology and Worship.

“As a young professional in the church, I’m humbled by Harold’s work and then I’m also humbled by this generous gift to our congregation,” Taylor says, “that will give back in so many ways, just like his writing and his scholarship on behalf of the denomination.”

Although Daniels had hoped to deliver his extensive collection to the church in person, because of his failing health—and subsequent death—the task fell to his wife Marie.

Delivery of the art. —Sara Ponton

Just over a month after Daniels died and two weeks before Holy Week, his widow and one of their sons delivered all 40 works of art to the church.

Taylor says that while Harold Daniels may have been the collector, it was Marie Daniels who was the lover of the art.

“Although it was his love of art that brought it into their home, for Marie giving the gift—actually being the one who drove from Albuquerque to Dallas to deliver it—was so incredibly personal,” he says. “It was so important to her that they carry out this wish because the day Harold passed away, he was still talking about it. He wanted to make sure that the art was taken care of and was going to have a good home. And so for her it was incredibly important that she be present to see where the art was going to be stored and where it was going to be hung.”

Plans for a dedication service, which Taylor hopes Marie Daniels will be able to attend, are under way. First, Taylor says, the church must make sure that the paintings are properly hung and appropriately lit so that the artists are honored, and through them, Daniels.

“I think that one of the reasons they wanted to make this gift was because they wanted the art to continue to serve the church, and that’s what we’re hoping to do with it,” says Taylor. “Through the stories depicted we can inspire other artists, our young people, and our congregation to ponder these stories in a different way through the visual arts.”

Taylor says that all of these intersections have helped him to more strongly appreciate “our Presbyterian world.”

“Harold truly embodies what it means to be the connectional church,” he says. “That someone who has given so much to the church would value a congregation he’s not connected with, and to which he would entrust the stewardship of his art collection, is just a beautiful example of the connectional church on display, which is such an amazing thing.”