When Crossroads International Fellowship Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) in Princess Anne, Md., closed its doors March 1, 2015, the loss was felt by the congregation and neighborhood. The storefront church had spent many years ministering to peoples' need in what its pastor, the Rev. Donna Bowers, calls “the poorest county in all of Maryland.” Yet, it hadn't reached a level of financial sustainability that would allow the congregation to continue.

Little did the grieving people of the recently shuttered multi-cultural church plant know that they would soon be brought together by tragedy to continue their ministry.

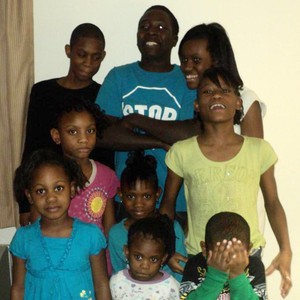

On April 6, eight people were found dead in a home near the church—seven of them were children who had regularly attended Crossroads. The father, Rodney Todd Sr., 36, had not been to work since March 28. His supervisor at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore dining-services notified authorities about Todd's unusual absence.

Police went to the home and discovered Todd and his children—the boys Cameron, 13, and Zhi’Heem Todd, 7; and the girls Ty’Juziana, 15, Ty’Keria, 12; Ty’Nijuzia, 11; Ty’Niah, 9; and Ty’Breyia Todd, 5—dead in their beds. A portable generator in the kitchen with several extension cords powering heaters and lights had run dry of fuel. The coroner cited the cause of death as carbon monoxide poisoning due to the generator exhaust not being ventilated from the home.

As news spread among those who had attended Crossroads, Bowers says people from the community came together, “just to be near each other.” Bowers walked through the crowd that had gathered to mourn the family, “giving and receiving hugs” and offering a time of worship. The church also organized a vigil where 20 former members joined with neighbors to honor and grieve the loss of the Todd family.

“We handed out flashlights to symbolize the light of God that was in the children,” she says of the church members' practical and symbolic gesture for those gathered. “We needed to remember to walk in the light.”

Bowers became pastor of Crossroads in August 2013. She and its members had worked to make the congregation a resource center, with a food pantry and community health outreach, in addition to striving to gather an interdenominational coalition to address community needs.

“Crossroads was a church for people who weren't comfortable with traditional church,” says Bowers. “It's where people who don't have a voice were welcome.”

Bowers says the Todd children began attending Crossroads four years ago, brought by the oldest of the children, Rodney Jr., 17, who was at his grandmother's home when the deaths occurred.

She describes the children as “polite and respectful” and Rodney Sr. as a “good dad who worked and took care of [the children.]” Bowers says he especially doted on the girls, braiding their hair in the latest styles. “He was better than most beauticians,” she continues, “He learned how to do it for his kids.”

The children became an integral part of the congregation, Bowers remembers, following a time when she had to stop worship because the children of the church were being “so antsy.”

“We just stopped worship and had the congregation move around so that each child had an adult sitting next to them. We had everybody learn the name of a child—which isn't easy because some of the names are difficult—and something about them,” she says of the timeout. “It started relationships in a deep way.”

“Many of the people in the church didn't have parents where there were appropriate relationships,” she says of the adults at Crossroads. “They took these kids under their wings.”

These relationships continued after the church closed, in the month preceding the children's deaths. “When we stopped doing our community meals [as a church], the congregation made sure these kids still ate with them,” says Bowers. “And the kids didn't come because they were hungry, they came because they wanted the relationship.”

Bowers is a registered nurse and was ordained a Presbyterian teaching elder in 2013. She continues to work in Princess Anne addressing issues of health and poverty, especially as it affects children. She describes the community as historic and one in which large houses have been subdivided into apartments that aren't very efficient.

Bowers says that heating one of these apartments during a cold winter like this last one costs many families $500-$600 per month. With rents roughly that same amount, for an approximate total of $1200 per month, she says many people couldn't afford both rent and heat, and looked for alternative means of heating. That's the course of action Todd took when he decided to use the gas powered electric generator in his home. Electricity to the home was shut off March 25 when Delmarva Power workers found a stolen power meter, noting that it had originally discontinued electric service in October, prior to the Todds renting the home. No request had been made to reconnect service.

A funeral for Rodney Todd Sr. and the seven children was held April 18 in which Bowers says she played a small part. She's been in contact with Rodney Jr. and says she and others from Crossroads will continue to help in any way they can.

“Even though the doors of the church are closed,” Bowers says, “we are still looking for ways to support [Rodney Jr.]”

Bowers recommends churches engage in community outreach regarding carbon monoxide poisoning, especially in areas where gas powered electric generators are used as an alternative to the tradition power grid. Educational materials are available at the Centers for Disease Control web site on the dangers of carbon monoxide poisoning and resources for its prevention. The CDC reports that more than 400 people in the U.S. died from carbon monoxide poisoning in 2014.