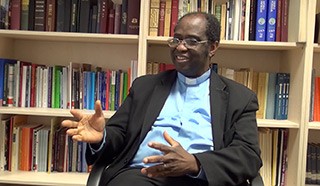

We talked to the Rev. Setri Nyomi, general secretary of the World Communion of Reformed Churches (WCRC), about his 14 years of service to the organization.

A video of the interview is available at http://vimeo.com/97152595.

What were you doing prior to becoming general secretary of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC, the predecessor of the WCRC)?

I was with the All Africa Council of Churches, which is the regional ecumenical organization in Africa, headquartered in Nairobi, where I was one of the two unit coordinators. In that structure, the unit coordinator has several other program staff under them and are the direct assistants to the general secretary in that sense.

Let’s step back further then; what brought you into the ecumenical world?

Well I’ve always been a theologian with a heart for the unity of the church and the church in action in the world. I’ve always invested Christian witness to include, yes, giving the good news of Jesus Christ to others who haven’t heard of Jesus Christ but also living out that good news in a way that affects the society. So justice issues have been very important to me for a long time. And I’m glad that in my formative years I found that the ecumenical movement was doing some of the things I thought were only on my heart. So from activity in the Christian Council of Ghana to working in the youth movement in my formative years to ensure that we were working together rather than on simple denominational lines has been always very important.

I used to teach in a theological college with an ecumenical theology — Trinity College in Ghana — which indeed gave me an opportunity again to team teach in a way which is not just one denomination but forming ministers together with other denominations. That is the same theological seminary I went to. So being ecumenical has been a part of my life for a long time in that sense. Meanwhile, much earlier than that, I was also on the youth working group of the World Council of Churches (WCC) as its vice moderator, between 1983 and 1991, between those two general assemblies. So I had quite a good exposure to activity at all levels of the ecumenical movement, on the national, regional and global.

So when you became general secretary, what do you think you brought to the position besides all of this experience?

I think, what I have received as a gift from the ecumenical movement is what I brought it. I received as a gift that the emphasis on the church has little credibility unless we are working in unity with the whole church. The divisions in the church, whether it’s in one denomination or along the lines of one denomination over against another, is a scandal. I have a strong conviction around that which I think I have brought in. The fact that the church has little credibility if it is not a counter-force against evil in the world, and injustice is a major evil in the world. I have a strong sense of that which I brought in to this position.

One of the backgrounds to that is that whenever I’ve gone into a situation in which the church is silent when there is evil, I simply can’t excuse that. And I raised questions when I was 18-years-old and went to Vicksburg, Mississippi, as an exchange student and saw that the church was way behind in terms of responding to racism than even the culture was. This was a year after schools were forced to integrate and churches were still operating along lines of “this is a white church, this is a black church.” I told myself that this was unacceptable. Even as an 18-year-old I felt the church needed to do something about it. So these are some of the backgrounds of a strong feeling of faith in the Lord Jesus Christ that needs to be shared; also it needs to be accompanied by a passion for making a difference in God’s world. I brought all these in.

One of my first interviews in the year 2000, I said I was an African and that no one was going to take that African-ness out of me, and I think that was also something that I brought in. This organization is a worldwide organization. I believe that each of us bring gifts that have to do with how we were shaped, from where we were shaped, and the African value for communal life, for deciding on things together, for ensuring we are moving together as a body and not just as a one-person leadership are things that meant a lot to me. The value for receiving the different gifts that each part of the world brings into this organization comes from that, from the, if you like, the feeling of ubuntu, we are not complete without the others in the community.

These were all things that I count as things that I brought into this organization — and all that lead to my values for the team work. Speaking just before our executive committee, I couldn’t see myself as playing my role as general secretary unless the consultation I need to do among my staff colleagues we have done. And at the same time, I see the role of the executive committee as we are in that as a team together, as well. So it’s not ever a “we-they” thing as far as I’m concerned. And that’s part of how we’ve carried ourselves in the past 14 years. It’s been very important to me.

I’ve always worked on the basis of if you focus on what needs to be accomplished, in a clear vision, you will have challenges. But the challenges should not have the final word. The focus on the things to accomplish should always be the driving force. In these 14 years that is the one value which has made us able to work even under the most difficult constraints financially, where the finances could have distracted us a lot more than they have attempted to do sometimes, but focusing on the tasks that must be accomplished, the vision we have, has trumped the concern over the finances.

Did you come in with some initial goals as general secretary?

Yes, one cannot come into a position like this without initial goals. I was actually very excited about the history of the then-World Alliance of Reformed Churches. I read Marcel Predavane’s book, A Century of Service, and the more I read it, the more I got excited about this organization which has accomplished so much in its existence since 1875 and its clear commitment to Christian unity and actions that make a difference in the world. And so I came telling myself that the one thing our being able to hold together those two things we should never step back from. And whatever I do in this position holding together the quest for Christian unity and making a difference, especially in the area of justice in this world, should be a clear focus.

The second thing for me was I knew how painfully in the Reformed family we are the most apt to divide. So I wanted to lead an organization in which this body could be a safe space for discussing difficult things but also the organization which could be trusted when divisions are occurring somewhere for us to be able to mediate and help them overcome if possible, because it’s kind of a loss for us to simply to accept the divisions because it’s what Reformed churches do. So at the very least I felt those two need to be identifiable goals in which we can make a difference.

Then I made myself open to what I would learn in this organization in the first two years of ministry because I was very much aware that I was coming into something new; and that had things that I may not know. So I told myself the third thing that’s important in at least those first two years is the need to be learning years for me to know what is important for this organization that I can feed into and build on what my predecessors have done, because I believe they have done a lot, and my job was to build on that, and to build on it properly I have to be a learner, as well. So these are the things I will point to as goals that I had.

What were some of the challenges — and not just the challenges but the learnings — that you found in those first two years, that you had to deal with or carry forward?

Well, most of my challenges had to do with the finances. I did know that the organization did not have the millions of Swiss francs it needed. But I was even more surprised about how challenging it was. We had less than I thought we had. So that was quite a difficult challenge. I think one of the images that described it was soon I discovered we were called upon to make bricks without straws. And yet I found willingness at many levels to be part of this organization.

In the first couple of years I traveled around quite a bit — more than I do now — because I wanted to meet the constituents and discovered everywhere that there was enthusiasm about the organization. When we start talking about money they might start raising their own contextual financial challenges, but each time we talked about how important the World Alliance at that time was to them they were excited with me.

And they were also doing things on the ground, sometimes different from how we approached things, but they were doing things that were exciting. And I learned in that process that what we do as Alliance, or now as a Communion, is not always what we in Geneva think through and say, “This is what churches need to be doing for justice to be achieved.” But I needed to sharpen my skills at listening and affirming what churches are doing even if it’s not exactly what my vision of justice is — and then to help link it with what we are doing. That was quite a challenging learning, but I’m glad we went through that, and that was before the Accra General Council. I think that probably helped churches which may have looked at what the Communion was doing justice-wise with some suspicion begin to hear that their approaches were also being taken into account.

Let’s talk about the Accra General Council and the confession that came out of it. What was that process like? Where did it come from? And how did it all come together?

As I indicated before taking this position, I was quite excited about the achievements of this organization. I knew in the 1990s they went through this process of regional consultations about the global economy, and especially the Africa meeting which was held in Kitwe, Zambia, was very clear that unless economic injustice was tackled with the same fervor that apartheid was tackled, the World Alliance would have no credibility. So they actually called for a strong action. I was in Debrecen in 1997, not as general secretary but as a consultant to one of the sections, and that was when they took the decision of processo confessionis on economic injustice and climate injustice. And I was proud as a Reformed person to see this body, which I didn’t know at that time I was going to be leading, take steps of that kind.

So I came in saying, well, there’s a process in place, put in place before I came, thankfully, so I didn’t even need to invent that anew. How can we engage in that process that leads to some definite results in Accra? So that’s the process that we led from 2000 to 2004, having some more regional consultations, having a clear aim in Accra to have something that would be something definite. And in Accra we brought all those in, and thankfully it resulted in the acceptance of a confession, to give the clear point to us that this is not simply a peripheral issue. This is at the core of our calling. And we needed a confession. In the Reformed tradition, we have had confessions whenever our faith is at stake there is a state of confusion that, based on the Word of God, we need to say something clearly. And so these are some of the things that led to that confession. We had the people in place from different regions to put the points down. We had a vigorous debate, but everybody was ready to accept that direction we had immediately. But the vigorous debate led to the Accra Confession, and I’m thankful for that.

What do you think the confession’s importance is today, ten years later?

The issues that the Accra Confession talked about are still with us. And in fact they are expressing themselves in more vicious ways than they were in 2004. We still have economic injustice, we still have many, many, many people dying as a result of the way the global economy is shaped. Since 2004, that has also touched the global north in a way that couldn’t have been envisioned in 2004. In 2004 people thought, “Oh, that’s the issue for Latin America, and Africa and Asia.” But in 2008 we had the economic meltdown that impacted the north and I personally had letters from people in the global north saying, “Looks like this is the very thing the Accra Confession is talking about.”

And so ten years later we have those issues still with us. For me the unfortunate thing is I don’t see how it is being lived out, even in the lives of our church members, to the extent I would have liked to see. If I had any evaluation of the Accra Confession I would count that a failure, that it is still not part of the mainstream of the life of people. And I hope this tenth anniversary we’ll be able to do that kind of evaluation and redirect ourselves because it’s not the kind of confession that you put on a shelf and say, “We’ve achieved a good statement.” It’s not even the kind of confession that you’re happy about if once in a while you recite it in churches as one of the wonderful confessions of the church. It is one that calls on us to engage in some actions, and unless we are doing those I would say we need to say we have failed.

So there’s justice. You also talked unity, and I guess the pinnacle of that was the Uniting General Council and the formation of the Communion. Could you lead us through that?

The important thing that drew the Gospel writers and our Lord Jesus Christ himself to comment on constantly is Christian unity. And John, chapter 17, is one key passage we keep referring to where the Lord prayed that the church, or that his followers, may be one. And the Godhead — the Trinity — speaks to us on the importance of unity. Our oneness is supposed to be modeled over as the Triune God is one. So that’s one thing that I’ve always felt the church needed to focus on. In this sense, I’m not simply having when the Reformed are one. I like the fact that we always say, “To be Reformed is to be ecumenical.” Our calling is to also contribute to the oneness of the whole church, not just the Reformed family. But we, of all families, are often the most apt to divide.

And in the year 2000, I came to see that there were five global organizations serving the Reformed family alone. This was unacceptable. I was happy again that I could build on what had been happening before because the Reformed Ecumenical Council (REC) and the WARC had since 1988 engaged in some conversations together. So I asked myself how could we deepen those conversations so that at least two of the five — and the two biggest of the five (the World Alliance was the biggest and the next was the REC) — at least those two biggest could show some form of unity. So we did place some emphasis on those conversations. And in the year 2004, we raised the question whether or not we could increase what we call cooperation at the time. And at that time I must confess we did not talk about organic unity; we didn’t even think about it. But at least if we can give a sense that we are together in how we do things that will satisfy what I thought was my goal.

In the year 2006, when we met in Grand Rapids on a very cold day — and I don’t like cold weather — those three days of meetings yielded something which was beyond what any of us in that meeting could have set as a goal. And I will always say that very clearly and honestly. None of us went to that meeting feeling we would leave here with a decision to become one body. We went with a goal of working more closely together. But the Holy Spirit is the Holy Spirit and we cannot dictate to the Holy Spirit. Our first meetings were to share with one another what is important for us, what our vision is, what we see as differences between us. By the end of the day we were asking the question: why are we not one organization? And that’s what started the moves. While I’m being careful not to claim that we orchestrated it and it came from our wonderful human planning, I will say this: that indeed once the decision was made, it was what met my wildest dreams of how we can be one together, and the next three years of working on that vision together were very fulfilling. That we could express to the whole world that the Reformed can also overcome division, and then it comes to strengthen what we try to do for congregations facing division, for churches facing division within our ranks, because at the global level we have demonstrated that we can.

What’s been your greatest joy of being general secretary?

Seeing what our churches doing effectively. When I visit our churches — it’s not so much what we do. But seeing that Reformed churches are living and acting and working effectively in different parts of the world and what we do can resource them, can encourage them, can strengthen what they do. But the important thing is that they are doing wonderful things. It’s not all of them, but many are doing wonderful things in their regions.

The second thing I will point to is the dedicated staff teams that I’ve had to work with. In many organizations that I know if we had the limited resources that we had, it often leads to demoralization, it often leads to people who are wanting to simply do the little that belongs to their job, but I have not found that in this organization. We have always risen to the challenge and done more than we are called upon to do. And I will always point to the fact that the dedicated staff teams that I have worked with all along has been my joy. Yes, we’ve had challenges within those also, but that’s a different story. But overall, working with the kinds of teams that I’ve worked with has been wonderful in this.

And it’s also been a joy for me personally to know the family support that I’ve had from my wife, from my children, who have not only had to deal with long absences but even when I’m at home, my weird hours of working, I think if I didn’t have a supportive family in that I wouldn’t be able to work. So it’s a joy to see that it’s all around, not being working alone, but with all these circles. I started with the member churches and what they have done, and also with the staff groups I’ve worked with, and the role the family has played is all happening — wonderful joys.

Do you have any regrets?

I’ll say without mincing a word: no, I don’t have any regrets. We’ve had many challenging moments, but I’m glad I was called to this position, and I’m glad about things that we were able to do together in all these teams together. There are things we could have done differently in times of these 14 years, but I wouldn’t call those regrets. I was just pointing to one of the challenges that has to do with the finances; I think there are times that things could have been dealt with differently in terms to responses to our challenges. We are a human institution as well, so those come with the territory

What are you doing next?

God willing I’ll return home later this year, and I’ll be pastoring a church in a suburb of Accra so I look forward to going back to the basics. I was ordained as a pastor in 1980 and at that time all I thought I would be doing was being a pastor of a church, and for more than half of those 34 years I have done other things but pastor a local congregation. So I’m going back now to the basics of pastoring a local congregation. And hopefully contribute what I’ve learned globally to the national scene, as well.

So what do you think you’ll be taking back into the parish ministry from all this experience internationally?

Well let me preface it by saying while here in this position I have always told myself that what we do globally will be meaningless unless we always keep an eye to the local congregation, because that’s the basic unit of the church we serve. If we think we can be either in Geneva or Hannover and think we know it all without keeping an eye on how this will impact a congregation, we would not be effective.

Now in my next life, I will have to turn that around. If any congregation thinks that’s the only reality, that it, too, can lose track. I think every congregation has a responsibility to think of itself as part of a global reality — and how it takes into account in that global reality and the gifts of the bodies to which we belong, including the World Communion of Reformed Churches, can bring to us, to live out that global reality even as we are effective witnesses locally is very important. And I think that’s a gift I expect to bring to the local situation and also being part of the national church, to bring to my colleagues in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church in Ghana to which I belong. And so in a small way contribute to what I’ve learned all these years to our reality.

Do have any advice for your successor?

I always shy away from giving advice to others so I always take that opportunity to only express wishes because I believe the search committee and the executive committee went through a very good discernment process, and that it’s yielding a person called to serve this organization and believe he will do well. And I don’t think anybody should burden him with advice on what to do and what not to do. I can only say I only wish this organization remains a strong force on Christian unity and on justice in the world and remains a safe space for all the members with all the variety, from the very conservative to the very liberal, to feel safe enough to discuss difficult questions and yet stay together and witness together. That’s my wish. How it will be done or whether or not it will be done, I trust in the wisdom of the new general secretary to be able to lead in his own way.

Anything else you want to say about your 14 years?

It’s been a good 14 years. It’s been challenging. It’s been years in which we can point to some milestones for which I think we as a team can be happy about and we thank God for what has been achieved. It’s also been years in which — we are human. There may have been problems — or there were problems — and if there are defaults that people have found about my leadership, I’m human, and I know there were many of those. I’m sure I’ve learned from some of them, but I know there have been some of those, and then I would hope that the evaluation decides that the feedback would help the organization in moving forward.

I would also always hope that the good leadership we’ve had in terms of governing body working in close tandem with management will continue. My thoughts in the last 14 years, the only times I was challenged was when governance and management was mixed up in a way in which often governors felt like doing things that governance is not called upon to do and that I would this organization would keep on watching for — so that we can have a healthy organization going forward.

For the most part we’ve done that and I thank God for the successive presidents we’ve had and the successive executive committees we’ve had which has led in that direction. This is the third set I’m working with, and I thank God for all those. And I thank God for the opportunity to serve this family of churches. It will always remain in my heart wherever I go. These years have been precious and I will continue to cherish them. And I will continue to think about this as my family.