In pre-modern days, Korea was frequently ravaged by deadly plagues of smallpox, cholera, typhus and typhoid fever.

When a plague was sweeping across their land, rulers of Korea’s Joseon Kingdom, including the king and all the staff of his royal medical department, stood defenseless. Korea’s traditional medicine based primarily on herbs, acupuncture and pulse reading ― as in ancient China ― was absolutely useless in dealing with a germ-borne epidemic .

Totally in the dark in the science of microbes, germs, vaccination and sterilization, Koreans for centuries had believed that plagues were the work of evil demons and accordingly sought to ward them off with the only methods they believed to be effective: praying to the god of the plague at a temple built especially for the deity and exploding firecrackers to frighten the demons.

In the countryside, farmers would employ local shamans to perform rituals mixed with dancing and singing at a village entrance to prevent the plague demons from entering their villages.

All this changed thanks to the goodwill of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), which gave birth to Korea’s modern medicine based on science in the early 20th century. Today, Korean medical science is one of the most advanced in the world and is the envy of other Asian nations.

Korea’s medical modernization began with brave and self-sacrificing American medical missionaries of the PC(USA), including Drs. Horace Allen, John Heron, Oliver Avison (originally from Canada), Cadwallader Vinton and Lillias Horton Underwood, beginning in 1884. Their work was financed by Louis Henry Severance, a wealthy Presbyterian in Cleveland.

Their pioneering work on Korea’s modern medicine and health care, however, encountered many difficult hurdles. Closed to the outside world, especially to the West, Koreans looked upon foreigners with fear and suspicion. At one point, even a vicious rumor appeared in the capital that foreigners were cannibals.

Reminiscing about her personal experience in Seoul in 1888, Lillias Horton Underwood wrote in her book, Fifteen Years Among the Top-Knots: “Babies, it was said, had been eaten at the German, English and American legations, and the (missionary-run) hospital, of course, was considered by all the headquarters of this bloodthirsty work, for there, where medicine was manufactured and diseases treated, the babies must certainly be butchered.”

In addition to the people’s fear and suspicion, the missionary doctors had to overcome centuries-old cultural taboos, especially the Confucian ethical code absolutely forbidding any act of intentionally cutting any part of one’s own body and accordingly outlawing any form of surgery.

The first big break came on Dec. 4, 1884, when Dr. Horace Allen saved the life of Min Yeong-Ik (1860-1914), a close relative of powerful Queen Min and a trusted advisor to the royal court. When Min was seriously infured in a failed armed insurrection by an opposition political faction, the royal court turned to Dr. Allen and his “foreign medicine” in desperation. Dr. Allen was successful in saving the dying royal advisor valued by the King and the Queen.

Having gained the trust of the royal court, Dr. Allen proposed to establish a government hospital where he and other missionary doctors could treat Korean patients with Western medicine. The royal court consented and established, in April 1885, a government hospital named Gwanghye Weon (“hospital of far-reaching grace”).

Two weeks later, the name was changed, at the bidding of King Gojong, to Jejoong Weon (“hospital for all people”). This was Korea’s first hospital whee the missionary doctors, including Horace Allen, John Heron, Cadwallader Vinton and others began to introduce modern medicine and health care.

When Dr. Oliver Avison arrive in Seoul in August 1893 to assume the directorship of the hospital, he found it in a sorry state, ill-staffed, ill-equipped and ill-financed, under the mismanagement of inept government bureaucrats.

Determined to bring up Korea’s medicine and health care to high-level efficiency, Avison set a grand vision: building a modern hospital and establishing a medical school to train Korean physicians in western medical science.

First, he persuaded King Gojong to free the decrepit government hospital from the ineffective bureaucrats and place it under the Presbyterian Mission Board USA in ownership, operation and financing. Secondly, he embarked upon fundraising for the new hospital and medical school.

In April 1900 Avison came to New York to attend the Ecumenical Conference on Foreign Missions held in Carnegie Hall, focusing on “literary, evangelistic, medical, educational, industrial, women’s work and … current conditions in various parts of the world.” It was attended by 600 foreign missionaries from 50 countries and at least 200,000 pastors and lay leaders.

Avison, as one of 500 conference speakers, spoke on behalf of Korea: its poverty, the deadly plagues which had ravaged the country in 1887 and 1895, problems inherent in Korea’s traditional medicine and health care, and Koreans’ desperate need for modern medicine, physicians, nurses and medical facilities. He also spoke of Korea’s future and its potential to become a light to other nations in Asia.

Among the 200,000 attendees was Louis Henrgy Severance (1838-1913), an oil magnate, a close friend and partner of John D. Rockefeller, and the treasurer of Standard Oil. He was also a devout Christian, and elder and Sunday School teacher at Cleveland’s Woodland Avenue Presbyterian Church.

Most of all, Severance was a philanthropist committed to improving the conditions of human life in less developed nations. That was the reason why he was in Carnegie Hall in April 1900. Deeply inspired by Avison, Severance eagerly offered to help fulfill his vision of building a modern hospital and a medical school in Seoul.

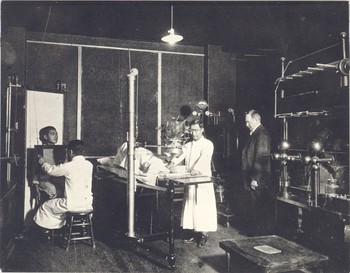

An x-ray room at Severance Medical School, c. 1920. —Presbyterian Historical Society photo

With an initial $10,000 donated by Severance, Avison completed the construction of a hospital in 1904 and named it Severance Memorial Hospital. Simultaneously he launched a medical school as part of the hospital.

Four years later, on June 4, 1908, the medical school graduated seven students, Korea’s first physicians trained in modern/western medical science. The following year the medical school was named Severance Medical School.

In 1906, Severance made a trip to Korea to see personally the fruits of his contributions. Upon returning home, he sent Dr. Alfred Ludlow, a renowned surgeon and his personal physician, to Severance Hospital to help advance Korea’s modern medical science, especially in surgery.

According to historians’ estimates, before he died in 1913, Severance had contributed today’s equivalent of a half-billion dollars to the advancement of Korea’s medicine and health care.

Severance Hospital and Medical School continued to grow, and in time became the finest hospital/medical school in Korea. In 1955, Severance Medical School and Yonhee Christian University ― another monumental work of PC(USA) mission ― decided to merge and become Yonsei University, one of the top three universities among 387 institutions of higher learning in Korea.

Consolidated into an impressive non-profit health care complex, Severance Health System now consists of three regional branches plus a dental school, nursing school, a hospital for mental patients and a graduate school of public health and nursing.

The main Severance Hospital, located on the campus of Yosei University, provides cutting edge health care in 25 areas, including asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, psychiatry, pulmonary disease and nuclear medicine. It also maintains 2,064 rooms for patients.

In 1996, Severance Medical School was rated by the Korean University Education Association as “the most outstanding medical school” among Korea’s more than 40 medical schools. In its 110-year history, it has trained more than 12,000 doctors. More than 1,000 of them have served in the U.S. as professors, cardiologists, oncologists, family doctors and medical researchers.

Others have volunteered to serve in Africa, the Middle East and other regions of the world in the footsteps of the brave and self-sacrificing missionary doctors who pioneered Korea’s modern health care in the spirit of Louis Henry Severance, whose motto was “It is more blessed to give than to receive and to serve than to be served.”

Far-reaching indeed are the blessings of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) to Korea and its 50 million people enjoying one of the best and modernized health services in the world.

Song Nai Rhee, Ph.D., is academic dean emeritus at Northwest Christian University in Eugene, Ore., and courtesy research associate in the Center for Asian and Pacific Studies at the University of Oregon.