The Rev. Candie Blankman, pastor of the multi-cultural urban First Presbyterian Church of Downey, admits that her Midwestern, suburban and fairly homogenous small town upbringing might seem a world away from her current call.

But a world away — the Philippines and Japan — is actually where much of it began.

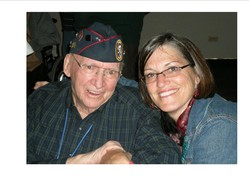

Blankman’s discovery came out of the process of writing her first book, the self-published “Forged By War: A Daughter Shaped by a WWII POW Story.”

“Writing the book started out being just my determination to get my father’s story in writing so that my children would know it,” said Blankman, who began the process of documentation in the late 1980s.

“I started interviewing my dad every time I went home to visit and would take time to ask him about his experience as a POW (prisoner of war),” Blankman said.

After about eight years of these storytelling sessions, Blankman entered seminary, got busy and allowed the project to stall. In the late ’90s, her father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease; by 2003, he no longer knew who his daughter was. He passed away not long after.

“Even though I got busy in ministry and life, I always had it in the back of my mind that I would love to travel to the places where he had been — to actually see them, smell them, touch them,” said Blankman.

When she found out about the clergy renewal program through the Lilly Foundation, Blankman decided it might be a way to accomplish two goals — retracing her father’s footsteps and exploring more deeply multicultural ministries — something she had found herself immersed in since being called as pastor to the ethnically diverse milieu of her Los Angeles community.

“In my mind at the time I had trouble reconciling how those two fit together — I could do it, but it was a bit of a circuitous route to get there,” Blankman said. “But once I began to travel in Asia and then started to paint, write and blog about it, it became very clear to me that they were intricately woven together.”

Blankman began to realize was that who she was as a person and as a pastor were both very deeply imprinted by what her father had experienced as a POW in WWII and how that had shaped her life.

“Largely what we experience in America today is the result of these men and women who came home and continued to sacrifice and serve their families, communities and churches in the same way that they sacrificed and served in WWII,” Blankman said. “But they never talked about it.”

Most books that have been written on the subject, Blankman notes, have only come about in the past 10-15 years.

“My book is in a sense the sequel, of what it was like to be raised by someone who suffered what he suffered. It wasn’t a case of mere survival, but someone who thrived out of those circumstances and who taught me to do the same,” Blankman said.

It was in the writing down of her father’s story, woven together with her own, that Blankman came to understand herself even more than she understood her father.

“Here I was, this Anglo, white Midwesterner raised in a middle-America full of Swedes and Norwegians, but finding myself in this very diverse multicultural church,” she said. “So how did I end up in a place where my main focus and vision of ministry was to open up to people of very different cultures and languages? I realized — it really harkens back to my dad.”

As Blankman wrote her dad’s story, she began to realize that through her childhood her dad was always bringing people to their home — people who were different from them. She recalled a young man from Africa, Bible school teachers from New York, but then it struck her with its significance — a Japanese couple.

“When I was about 11 or 12 they came to our house for dinner. And at the time I had no idea how significant that was, that my dad, a Japanese POW who came close to death over the three and a half years he was held prisoner, opened his home, his heart, to a Japanese couple,” said Blankman, choking up as she recounted the memory.

But equally astounding was the fact that the Japanese man had lost his entire family in the bombing of Hiroshima. “There they were — two men who had experienced incredible loss and pain and brutality at the hands of the other, and yet were able not only to speak to each other, but to rise above that and express love and appreciation for each other because of their mutual faith in Christ.”

Not long ago, in the church where she is currently pasturing, an older man came up to Blankman, indignant that they were ‘catering to the Koreans.’ The ‘Korean’ in question was actually Vietnamese, helping to lead in worship.

“He didn’t even have the ethnic identification correct, and asked me why we were catering to the Koreans when we had fought a war with Korea,” Blankman said.

“He’s not Korean, he’s Vietnamese — and we fought a war with them too,” she responded.

“My dad was a POW of the Japanese for three and a half years and he brought a Japanese couple into our home and welcomed them — and I kind of think that is what the church is supposed to do,” Blankman said.

Erin Dunigan is a freelance writer, photographer, and pastor who lives in a small coastal community in Baja California, Mexico when she is not following her wanderlust out into the world.