Prep 4 Min

About this blog

The Rev. Timothy Cargal, Ph.D., serves as Assistant Stated Clerk for Preparation for Ministry in Mid Council Ministries of the Office of the General Assembly.

“... the Land that I Will Show You” is the blog of the Office of Preparation for Ministry of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). This blog is designed to serve as a resource for those discerning and preparing for a call to the ministry of Word and Sacrament as ordained teaching elders of the church. It will also provide a place for reflecting on and dialoging about the changing context of pastoral ministry in the early 21st century.

For quick announcements about changes or developments in the preparation process, dates related to exams or other key events, discussion boards, surveys, etc., you can follow us on Facebook at “Preparing for Presbyterian Ministry.”

Recent posts

- Clarification of Evaluation Standards for the Standard Ordination Exams

- BCE Preparation Resource Released

- PCC Responds to September 2016 BCE

- PCC Letter on BCE Preparation

- Bible Content Exam Results

Categories

- Ordination Process (34)

- Ordination Exams (30)

- Ministry Context (16)

- Ordained Ministry (8)

- Bible study (2)

- View all categories →

Archives

New Formats for BCE Questions

My two previous posts have reviewed changes coming to the Polity, Theology, and Worship exams in response to referrals from the last General Assembly (2014). In this post I will go over changes approved by the Presbyteries’ Cooperative Committee on Examinations for Candidates (PCC) related to the Bible Content Examination (BCE). These changes will take affect beginning with its next administration on September 4, 2015.

My two previous posts have reviewed changes coming to the Polity, Theology, and Worship exams in response to referrals from the last General Assembly (2014). In this post I will go over changes approved by the Presbyteries’ Cooperative Committee on Examinations for Candidates (PCC) related to the Bible Content Examination (BCE). These changes will take affect beginning with its next administration on September 4, 2015.

The BCE differs from the other standard ordination exams in almost every way. The senior exams in the areas of Bible Exegesis, Church Polity, Theological Competence, and Worship and Sacraments are designed to be taken toward the end of seminary as assessments of an ability to integrate what has been learned through graduate theological education with the practice of ministry. The BCE is designed to be taken early in seminary to assess whether one has the basic familiarity with scripture required for success in both theological studies and ministry, and to guide as necessary course selections in biblical studies while in seminary. The senior exams use extended written responses to ministry case studies as the means of assessment, while the BCE uses short, objective questions about the stories and themes of the Bible.

For many years now the BCE has utilized the “multiple-choice” question format exclusively. That, however, has not always been the case. In the past the exam has also included so-called “matching” or “ordering” questions that also are objective in nature and capable of “machine grading.” The PCC has made the decision to re-introduce those question formats to the BCE. Let me provide an example of each type of question and how it would work in the online testing system.

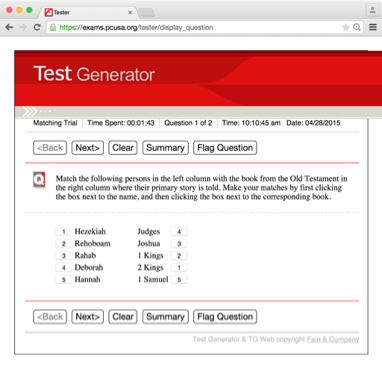

A “matching” question requires pairing listed items in a left-side column with their corresponding partners in terms of the question posed listed in a right-side column. In the example provided here, persons named in the Bible are listed in the left-column and are to be matched with the biblical book in the right-column where the primary story about the person is to be found. The pairings are entered in the testing system by first clicking the box next to the person’s name (thus assigning it a number) and then clicking the box next to the corresponding book, so that the same number appears next to each partner in the pairing. Or, the person may first click the box on the right for the book and then the box on the left for the name. The pairings can also be made in any order, not just by working straight down either the left side or the right. The key is that each pair is “matched” by having the same assigned number.

A “matching” question requires pairing listed items in a left-side column with their corresponding partners in terms of the question posed listed in a right-side column. In the example provided here, persons named in the Bible are listed in the left-column and are to be matched with the biblical book in the right-column where the primary story about the person is to be found. The pairings are entered in the testing system by first clicking the box next to the person’s name (thus assigning it a number) and then clicking the box next to the corresponding book, so that the same number appears next to each partner in the pairing. Or, the person may first click the box on the right for the book and then the box on the left for the name. The pairings can also be made in any order, not just by working straight down either the left side or the right. The key is that each pair is “matched” by having the same assigned number.

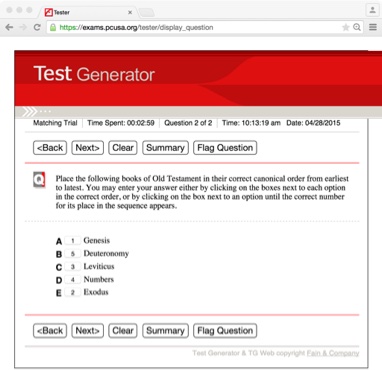

In an “ordering” question there will be a single column of items, and the question will prescribe how they should be arranged in terms of their relationships to one another. In the example here, the sequencing of the items is to be the order in which the books occur in the biblical canon. Other possible sequences might include such things as narrative order (“place the following stories from the Gospel of John in the order in which they appear in that book”) or chronology (“place the following kings of Judah in their proper chronological order as recounted in 1 Kings”). In keeping with the parameters of the BCE, any chronological ordering question would utilize chronologies within biblical books themselves and not historical reconstructions by scholars. The ordering is entered into the testing system by clicking the boxes next to each item in the list in the proper order, or by clicking the box next to the item until the appropriate number for its place in the sequence is displayed.

In an “ordering” question there will be a single column of items, and the question will prescribe how they should be arranged in terms of their relationships to one another. In the example here, the sequencing of the items is to be the order in which the books occur in the biblical canon. Other possible sequences might include such things as narrative order (“place the following stories from the Gospel of John in the order in which they appear in that book”) or chronology (“place the following kings of Judah in their proper chronological order as recounted in 1 Kings”). In keeping with the parameters of the BCE, any chronological ordering question would utilize chronologies within biblical books themselves and not historical reconstructions by scholars. The ordering is entered into the testing system by clicking the boxes next to each item in the list in the proper order, or by clicking the box next to the item until the appropriate number for its place in the sequence is displayed.

Although each “matching” or “ordering” set will appear in the testing system as a single question, it will be scored as if each element in the list were a separate question. So in the previous example, correctly identifying Genesis as the first book in the canon would earn one point, and identifying Exodus as the second would earn a second point. This scoring is used because the information provided in responding to one element in a “matching” or “ordering” set is equivalent to correctly identifying one alternative among the “multiple choice” options in a question. Since there can be a potential penalty in these forms of questions—associating Rahab with Judges in the example above assures that you must also have misidentified one other pair in the set—the PCC has set a limit of no more than 15 “questions”/points in the “matching” and “ordering” formats within each exam (thus, no more than three sets of five elements each).

So, why is the PCC making this change to the BCE? One reason is obviously the efficiency of developing and translating one set of “matching” or “ordering” elements as compared to what is involved in developing and translating five multiple choice questions. For example, using only the “multiple choice” format requires developing five separate questions to assess whether an inquirer can identify key thematic verses within five particular prophetic books; the same assessment can be accomplished with a single five-element set of matching. Having additional question formats also introduces some variety into the test.

More importantly, however, this variety and efficiency will hopefully help the PCC more quickly achieve its goal of developing a large database of questions that are not publically available and have known relative difficulties established through use in the BCE. With a sufficiently large and diverse pool of questions, it may eventually be possible to make the BCE available for administration more frequently than twice a year.

- Posted at 3:30 p.m.

-

- Tweet